Highlights

- Adult children with a sense of gratitude have long functioned as nature’s retirement safety net. But more childlessness will place more pressure on the government safety net. Post This

- Some predict that a crisis in senior homelessness looms. Post This

- Senior homelessness could be an emerging problem in some cities, even if it’s a manageable one. Post This

The share of Americans above age 65 is projected to grow in coming years, outpacing overall population growth by almost 20 percentage points by 2030. Some predict that a crisis in senior homelessness looms.

Senior homelessness has, traditionally, not been much of a concern for government because homeless people tend not to live very long. Life expectancy in the U.S. as a whole is 76 years old. Studies of homeless mortality often find an average age in the early fifties. With respect to the hardcore street population, the standard rule of thumb is to add two decades. Many unsheltered homeless people in their forties are functionally “seniors.”

But our government could have more homeless senior citizens (understood more conventionally) on its hands if there are more seniors around, especially seniors with qualities that place them at risk for becoming homeless.

Various “risk factors” exist for homelessness. One is social isolation. It has been wisely remarked that “People don’t become homeless when they run out of money, at least not right away. They become homeless when they run out of relationships.” Family relationships form the first line of defense against economic hardship. But family relationships can be strained by drug addiction or mental illness, or they can simply fail to develop in the first place.

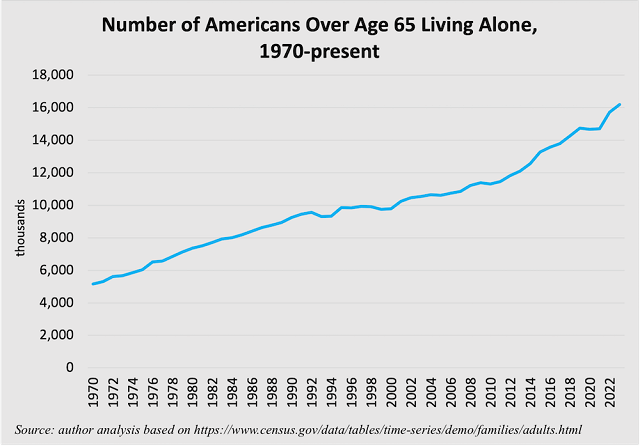

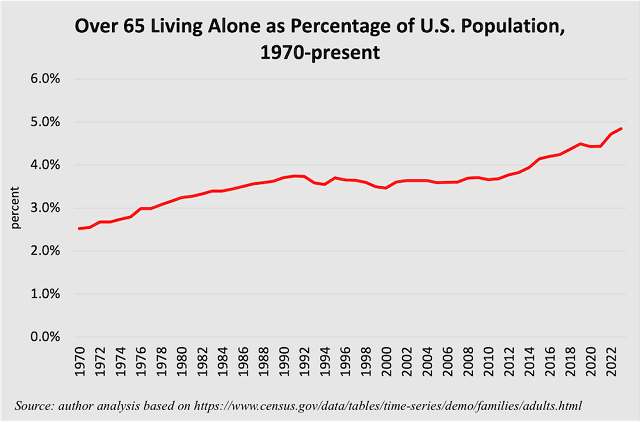

The number of seniors living alone has risen recently, both in absolute terms and as a share of the total population.

The penchant for solo senior living increases as societies become wealthier. The rate in America is about the same as Europe’s. “Developed” societies are more likely to view an 80 year-old still living all by herself as rugged individualism, rather than evidence of societal abandonment. More elderly dying and their bodies lying undiscovered for days is one risk we run with more people living alone. Another risk is more senior homelessness.

Smaller families could also be a society-wide risk factor. All things being equal, eras during which having four or more kids wasn’t a countercultural lifestyle were better positioned to handle problems such as chronic mental illness and elder care. Adult children with a sense of gratitude have long functioned as nature’s retirement safety net. It stands to reason that more childlessness will place more pressure on the government safety net.

In the retirement policy debate, conservatives have tended to downplay the risk of old age poverty. That is because conservatives believe that progressives talk up the threat of a broad-based “retirement crisis” to strengthen support for expanding the welfare state. This concern is not hysterical. Homelessness policy entrepreneurs play a similar game when they foreground more sympathetic subsets, veterans most notably, over more important, but ostensibly less sympathetic, subsets, such as addicts and schizophrenics. Advocacy dynamics may be at work behind some of the coverage of the “silver tsunami” of homelessness that’s supposedly about to hit.

But even if most households are reasonably prepared for retirement, it wouldn’t take many who aren’t to have an impact on existing homeless service systems. There are 650,000 homeless people in America. During the peak 18 baby boom years, a full 30 million more people were born than during the prior 18. And over 11,000 Americans turn 65 every day. How many overestimate their self-sufficiency? Some service providers claim to be noticing an increase in senior homelessness. In a September 2023 episode of the podcast “Rational in Portland,” a staffer from the Bybee Lakes Hope Center, an Oregon shelter, said “One of our largest populations is elderly women” whose fixed income doesn’t suffice to keep them from being homeless.

The Baby Boom drove the 1970s-era surge in mental illness-related homelessness that’s still with us. Serious mental illness develops in the late teen and early adult years. Though the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill began in the mid-1950s, so long as the Baby Boom generation remained children, mental illness-related homelessness remained rare. But 25 or so years in, and about a decade and a half into deinstitutionalization, the numbers of psychotic adults wandering the streets became more noticeable.

Senior homelessness is a different problem. The seniors we should be concerned about are those without families, who are not affluent but who have not lived an unusually unhealthy life (they’ve made it to 65). Living in a hot housing market is another risk factor. Twenty-somethings respond to high rents by either moving somewhere cheaper or sharing costs with roommates. These may be less realistic options for a 65 year-old who is more settled in her ways, having lived alone for 40-plus years in the same city, which lately is a lot more unaffordable. (Incidentally, the trend of more adults living alone itself pushes up rents for everyone.)

Someone like that is by no means necessarily destined to live out of a tent in San Francisco’s Tenderloin. High-rent cities tend to have large concentrations of shelters and other publicly-funded programs for the homeless. But those are often designed to handle chronically homeless single men, and are thus unsuited to care for a formerly working-class, 71-year-old childless widow dealing with her first serious encounter with housing instability. Some cities may need to develop more shelter spaces custom designed for seniors.

There is some good news, however.

First, there’s less community opposition towards residential programs for seniors than for chronically homeless single men. Indeed, senior housing is U.S. communities’ favorite form of “social” housing. Communities often run up the score on senior housing to try to avoid being stuck with development they find less attractive.

Second, to the extent that senior homelessness necessitates a welfare state expansion, this expansion should be targeted, not broad. The moral hazard risk will be low. It is doubtful that homeless people will start flocking to certain cities for no other reason than those cities’ ADA-accessible shelter stock.

Third, “service resistance” shouldn’t be much of an issue. Overcoming the unwillingness to accept help is, with many of the most troubled unsheltered cases, frontline service providers’ largest challenge. Everything runs more smoothly in homeless services when people take what you offer them.

Surveying the history of homelessness in America, the qualitative changes are more striking than the quantitative ones. It’s hard to know how much the size of the homeless population has changed over the years. It’s much clearer that family homelessness used to be totally unknown; now, however, most of New York’s homeless population are members of families. Alcoholic residents of “skid row” districts, back at mid-century, were disproportionately white; now, the street population is disproportionately black. As noted, homelessness among the seriously mentally ill used to be more rare than it is today. Senior homelessness could be an emerging problem in some cities, even if it’s a manageable one that—as of yet—does not deserve being called a “crisis.” It could require complicated and expensive accommodations for a population whose governments can no longer rely on families to handle.

Stephen Eide is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and author of Homelessness in America. He would like to thank Nohl Patterson for help gathering the data for this article.