Highlights

- Enduring, close, supportive relationships are what best predict whether people report being happy. Post This

- We can reprioritize our social connections at three levels—our fleeting contacts, friendships, and covenant partnerships. Post This

- For all people (whether single or married) supportive friendships feed human flourishing. Post This

Who is happy? What should you know about someone to predict their joyfulness? While sifting mountains of data for my book, The Pursuit of Happiness, and for my reporting since, I’ve been surprised by how little certain things, like one’s age, gender, or race, matter. Income and wealth help to a point—better to afford life’s necessities and feel in control than not. Yet beyond an “income satiation point,” ever-increasing wealth produces diminishing emotional returns. Once a millionaire, it hardly matters how many more millions sit in your bank accounts.

What does matter, big time—what best predicts whether people report being “very happy”—are enduring, close, supportive relationships. We are, as Aristotle observed, social animals. To be socially malnourished—as when ostracized, exiled, imprisoned, or bereaved—is to feel bereft. Solitary confinement is a dehumanizing punishment.

As social animals, we come with a built-in “need to belong”—to, as social psychologists Roy Baumeister and Mark Leary explain, “form and maintain strong, stable interpersonal relationships.” So it’s an anomalous fact that face-to-face interactions have waned. We’re not only Bowling Alone more often, to use Robert Putnam’s famous metaphor, we’re also spending less time socializing with others. Compared to the turn of the century, today’s adults under age 35 report spending half as many minutes per day hanging out with others.

As Jean Twenge has amply documented, today’s teens likewise have fewer friends, and are dating less, partying less, and spending less time with friends. A lot less, despite being less employed or doing less homework. And—no secret by now—what they are doing is spending much more time staring at screens and comparing themselves with others on social media—with a consequent decrease in sleeping and reading, and a doubling of depression since the spread of smartphones.

Our social malnutrition is further amplified by increased remote work, take-out food, and online shopping, and by decreased attendance at churches, museums, and school sports. With streaming worship and games, it’s so easy to “attend” from the comfort of our homes. Nightclubs are shutting down, and a leading party-supplier company is going out of business.

Three Levels of Reconnection

The drains on our face-to-face relationships are baked into modern life—we’re not giving up our phones or returning to the shopping malls. But we are not helpless. We can—to enhance our well-being and mitigate against loneliness and depression—feed our need to belong by reprioritizing our social connections. And we can do so at three levels—our fleeting contacts, our friendships, and our covenant partnerships.

1. Micro-friendship. Our moods get a boost not only from deep connections, but also from momentary face-to-face interactions. That’s the verdict of recent experiments that offered participants a small incentive, such as a $5 Starbucks card, to either (by random assignment) engage in conversation or not.

- After chatting with a barista (“smile, make eye contact to establish a connection, and have a brief conversation”), coffee shop patrons left the store feeling happier.

- After striking up a conversation with a Chicago commuter train seatmate (“try to get to know your community neighbor this morning”), extroverts and introverts alike exited their trains in a better mood.

After offering passing strangers a compliment about “something about them that you like” (often their hair or clothing), students unexpectedly found their micro-kindness warmly received, leaving both the giver and receiver feeling better.

The lesson: Reach out and talk with someone—perhaps a friendly exchange with the mail carrier or a wee blether with the ride share driver—and your kindness will be “twice-blessed,” uplifting you both.

2. Supportive Friendship. "Looking over the last six months, who are the people with whom you discussed matters important to you?” asked the National Opinion Research Center in a survey of Americans. Compared with those who could name no such confidante, those who named five or more such friends were 60% more likely to feel “very happy.” For social animals, stable friendships—“social support”—also serve to buffer stress and enhance health and longevity. It is gratifying when, in a conversational dance, we open up to someone and they reciprocate. By activating neural and cognitive systems associated with reward, self-disclosure is intrinsically rewarding. For both conversational partners, it feels good.

In experiments, University of Chicago social psychologist Nicholas Epley has demonstrated the satisfactions of this “disclosure reciprocity effect.” In a recent talk on my campus, Epley mused that we are social animals who, strangely, miss opportunities for social connection. He then randomly paired us with another to connect, by discussing three questions for 15 minutes: 1) “If I were to become a good friend of yours, what would be most important for me to know about you?” 2) “For what in your life do you feel most grateful? Please tell me about it;” and 3) “Can you tell me about one of the last times you cried in front of another person”?

We can feed our need to belong by reprioritizing our social connections. And we can do so at three levels—our fleeting contacts, our friendships, and our covenant partnerships.

Before the discussion, we all responded on our phones to questions about how awkward versus enjoyable we anticipated the conversation would be, and then rated our actual experience afterwards. The result: Our conversations were significantly less awkward and more enjoyable than expected. This matched his repeated findings: Reaching out to others for conversation, to express gratitude, or to discuss a difficult issue is more rewarding than people predict.

The lesson: For all people (whether single or married, as social psychologist Bella DePaulo reminds us) supportive friendships feed human flourishing. “People who eat frequently with others,” are also happier, reports the World Happiness Report 2025. A companion (com/with + panis/bread) is literally someone with whom we share bread.

So, taking the initiative to engage in meaningful conversation with friends and others is time well spent. We can put down our phones and give friends our focused attention. We can resolve to share more meals and coffees. We can stick our head into coworkers’ spaces. Sharing our lives with supportive friends has two effects, observed the seventeenth-century sage Francis Bacon: “It redoubleth joys and cutteth griefs in half.”

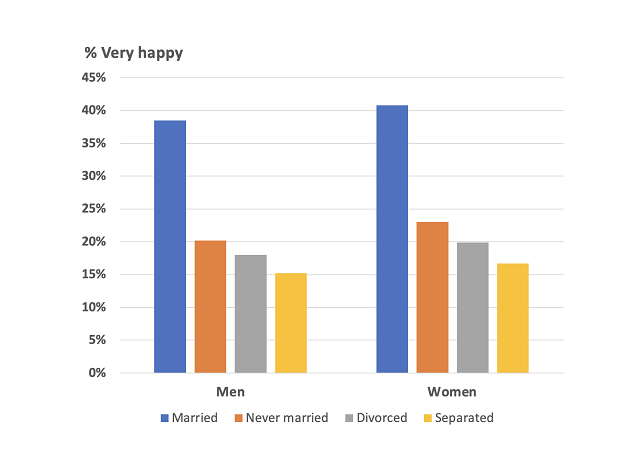

3. The Marriage Premium. Is friendship sealed by commitment—aka marriage—also beneficial? Does marital status predict happiness? It does, as sociologist Brad Wilcox amply documents in Get Married. By harvesting data from a half-century of General Social Surveys, I similarly observed that the marriage premium is substantial, and equally so for men and women, including same-sex couples—whether in the USA or the Netherlands.

Marital Status and Happiness: 1972-2011, GSS

Obviously, not all marriages are stably supportive. Paraphrasing social reformer Henry Ward Beecher, "Well-married, a person is winged—ill-matched, shackled." Among GSS respondents who declare their marriage as “very happy,” 57% have declared life as a whole to be very happy, as have only 5% of those in a “not too happy” marriage.

The Take-Home Lesson

Knowing that marriage matters, we can make marriage-supporting choices. We can prioritize communicating with our partner. In doing so, we can apply the latest findings from Nicholas Epley and his colleagues. In experiments, they matched people with someone of a kindred or opposing view on some hot topic, such as abortion, same-sex marriage, or immigration policy. In 10-minute conversations, the pairs then shared and explained their positions. Their consistent finding: When paired with a disagreeing partner, people expected an awkward, unpleasant conversation. But what they actually experienced was surprisingly satisfying—and much more so than listening to another’s monologue.

In other experiments, James Dungan and Epley found that roommates and romantic partners are similarly too pessimistic about the outcomes of hard conversations. Such anxious pessimism, they report, “may leave people overly reluctant to have the kinds of difficult conversations that are important for their relationships to thrive.” Martin Luther King, Jr., understood:

[People] hate each other because they fear each other. They fear each other because they don’t know each other, and they don’t know each other because they don’t communicate with each other, and they don’t communicate with each other because they are separated from each other. And God grant that something will happen to open channels of communication.

Today’s online conveniences and social media enrich our lives, but at the price of social disconnection. “In 2023,” testifies the World Happiness Report 2025, “19 percent of young adults across the world reported having no one that they could count on for social support”—a 39 percent increase from 2006. Young adult happiness has also decreased.

Yet there is good news: For those willing to venture connection—in casual conversations, supportive friendships, and sustaining partnerships—life is mostly good. As the 17th century dramatist Pierre Corneille divined, “Happiness seems made to be shared.”

David Myers, a Hope College social psychologist, authors psychology textbooks and trade books, including his recent essay collection, How Do We Know Ourselves? Curiosities and Marvels of the Human Mind.