Highlights

- Data from the American Time Use Survey reveal a concerning divide across family structures, with teens in two-parent households spending significantly less time in front of screens than teens in single-parent families. Post This

- This divide in TV consumption does not just play out across family structure, but race as well. Post This

- The marriage divide is impacting the lives of many adults across the country, but it also has important ramifications for the health, happiness, and outcomes of our children. Post This

We recently showed that television viewing habits offer one example of how the marriage divide plays out in the every-day lives of American adults today. But the ramifications of the marriage divide extend far beyond adults. Changes in the family landscape of America have also left millions of children at a disadvantage in life. Here, too, statistics surrounding screen-time indicate a “double disadvantage” for the millions of U.S. children who are currently being raised in single-parent and cohabiting families.

Higher levels of screen time are not only associated with poor health outcomes and high rates of obesity for children, they also have a damaging effect on children’s happiness, self-concept, and educational outcomes.1 For example, children who watch excess TV and spend more time playing video games have lower GPAs than their classmates, do not perform as well on standardized tests, are more likely to fail classes, and are more likely to exhibit disruptive or violent behaviors.2 Adolescence is an extremely formative period in a person’s life, and teenagers who spend more time in front of the TV screen often miss out on critical opportunities for educational and personal growth.

Screen-time habits may even act as a barrier to children completing what Isabel Sawhill and Ron Haskins call the “success sequence,” the sequence of steps that include the completion of education, working full-time, and waiting until marriage to have kids (in that order). One recent study followed a cohort of middle- and high-school students in the 90s through their adults lives, finding that teenagers who spent more time watching television and playing video games in adolescence were significantly less likely to obtain a bachelor’s degree in their adult life and less likely to successfully move out of their parents’ home as a young adult.3

Recent research has also shown that TV exposure in adolescence influences the sexual beliefs and practices of young adults, and that exposure to mature video games in adolescence is associated with greater engagement in risky sexual behaviors later in life, along with higher levels of aggression and delinquency.4 Enjoying television and video games in moderation may certainly be a harmless practice for millions of children. But the research paints a clear picture that excessive screen-time frequently contributes to undesirable outcomes for children.

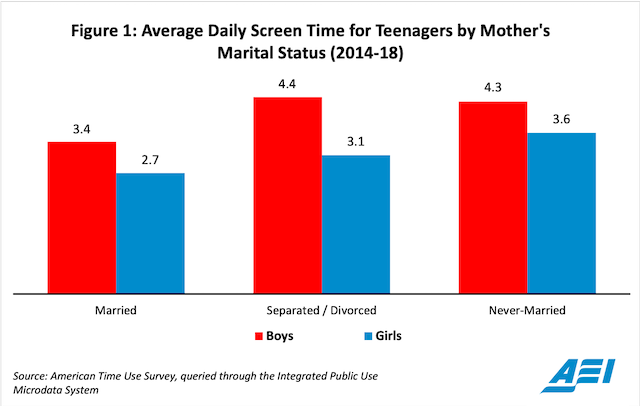

So, how does screen-time compare for adolescents across different family structures? As figure 1 shows, data from the American Time Use Survey on the technology habits of teenagers reveal a concerning divide across family structures, with teens in two-parent households spending significantly less time in front of screens than teens in single-parent families.5 For this analysis, we included television viewing, leisurely computer use, and video gaming.

This trend appears especially pronounced among teenage boys. While teen boys living with a married mother spend an average of 3.4 hours per day watching TV, gaming, or using a computer for leisure, those living with a divorced mother spend an average of 4.4 hours each day—that’s nearly a 30% increase in screen time! For teenage girls, living with a never-married mother generally means about 54 minutes of additional screen time each day—a 33% increase.

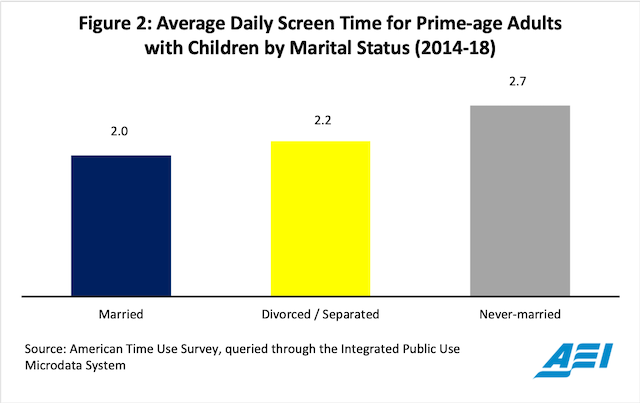

Also of concern, this trend is not only true for teenagers living in single-parent families, but for their parents as well. As figure 2 shows, married parents spend less time on average watching television, playing games, and using a computer for leisure than divorced and never-married parents. With children in single-parent families already at a higher disadvantage when it comes to life outcomes and overall well-being, parental screen time use could compound these disadvantages.

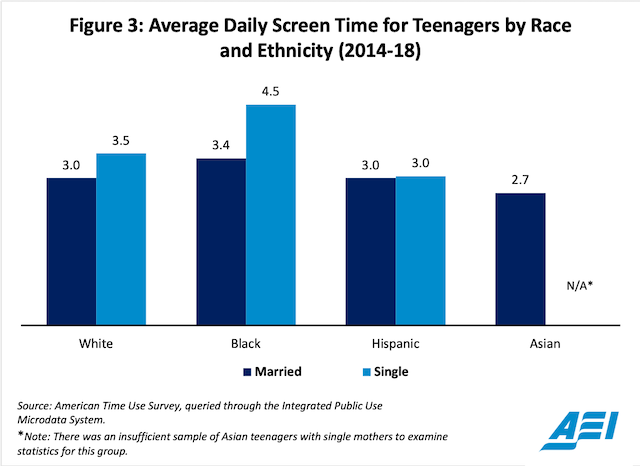

This divide in TV consumption does not just play out across family structure, but race as well. As figure 3 shows, Black boys and girls in single-parent homes spend the most time in front of a screen compared to their peers in married families. Asian teens in married families, on the other hand, spend less time in front of screens than any of their peers.

The data presented above offer a compelling example of how the marriage divide is leaving many children and teens at a disadvantage in life. Without having two parents present to regularly invest in their growth and development, many children in single-parent and minority families find themselves filling more of their time with TV and video games, and spending less time on activities that will contribute to their social and educational growth. The marriage divide is impacting the lives of many adults across the country, but it also has important ramifications for the health, happiness, and outcomes of our children.

Peyton W. Roth is a Research Assistant in poverty studies at the American Enterprise Institute. W. Bradford Wilcox is a Visiting Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and a Professor of sociology at the University of Virginia.

1 Holly Wethington, Liping Pan, and Bettylou Sherry, “The Association of Screen Time, Television in the Bedroom, and Obesity Among School‐Aged Youth: 2007 National Survey of Children's Health,” Journal of School Health 83, no. 8 (2013): 573–581; Robert J. Hancox, Barry J. Milne, and Richie Poulton, “Association between child and adolescent television viewing and adult health: a longitudinal birth cohort study,” The Lancet 364, no. 9430 (2004): 257–262; Bruno S. Frey and Christine Benesch, “TV, Time, and Happiness,” Homo Oeconomicus 25, no. 3–4 (2008): 413–424; Mark D. Holder and Ben Coleman, “The contribution of temperament, popularity, and physical appearance to children’s happiness,” Journal of Happiness Studies 9 (2008): 279–302; Karen R. Perkins, “The Influence of Television Images on Black Females' Self-Perceptions of Physical Attractiveness,” Journal of Black Psychology 22, no. 4 (1996): 453–469; and Nicole Martins and Kristen Harrison, “Racial and Gender Differences in the Relationship Between Children’s Television Use and Self-Esteem: A Longitudinal Panel Study,” Communication Research 39, no. 3 (2012): 338–357.

2. Patricia A. Williams et. Al, “The Impact of Leisure-Time Television on School Learning: A Research Synthesis,” American Educational Research Journal 19, no. 1 (1982): 19–50; Vivek Anand, “A Study of Time Management: The Correlation between Video Game Usage and Academic Performance Markers,” CyberPsychology & Behavior 10, no. 4 (2007: 552–559; Iman Sharif and James D. Sargent, “Association Between Television, Movie, and Video Game Exposure and School Performance,” Pediatrics 118, no. 4 (2006): 1061–1070; and Elif Ozmort, Muge Toyran, and Kadriye Yurdakok, “Behavioral Correlates of Television Viewing in Primary School Children Evaluated by the Child Behavior Checklist,” Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 156, no. 9 (2002): 110–114; Sarah M. Coyne et. Al, “Violent video games, externalizing behavior, and prosocial behavior: A five-year longitudinal study during adolescence,” Developmental Psychology 54, no. 10 (2018): 1868–1880.

3. Andrew Latinsky and Koji Ueno, “Leveling Up? Video Game Play in Adolescence and the Transition into Adulthood,” The Sociological Quarterly (2020).

4. Jeremiah S. Strouse and Nancy L. Buerkel-Rothfuss, “Media Exposure and the Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors of College Students,” Journal of Sex Education and Therapy 13, no. 2 (1987): 43–51; L. Monique Ward, “Does Television Exposure Affect Emerging Adults' Attitudes and Assumptions About Sexual Relationships? Correlational and Experimental Confirmation,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 31 (2002): 1–15; and Rebecca L. Collins et. Al, “Watching Sex on Television Predicts Adolescent Initiation of Sexual Behavior,” Pediatrics 114, no. 3 (2004): 280–289.

5. Sandra L. Hofferth, Sarah M. Flood and Matthew Sobek, American Time Use Survey Data Extract Builder: Version 2.7 [dataset], College Park, MD: University of Maryland and Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2018; To approximate daily screen time for children, we combined the time respondents reported spending on the following activities: “watching television,” “playing games,” and “computer use for leisure.” Unfortunately, the American Time Use Survey does not distinguish between electronic and other games in the “playing games” measure, so this variable does capture the time respondents spend playing Solitaire and Call of Duty alike. A measure level of error is thus endogenous to the “screen time” measure used in this study. However, previous studies have documented a very large increase in the amount of time teenagers report “playing games” throughout the 2000s as the popularity and availability of video games have increased, which suggests the “playing games” variable primarily captures time spent on video games, not other games. See Mark Aguiar et. Al, “Leisure Luxuries and the Labor Supply of Young Men,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 23552, June 2017.