Highlights

Donald Trump’s election as president focused national attention on the declining fortunes of many older American men. However, “Leisure Luxuries and the Labor Supply of Young Men,” a recent working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), indicates that the bottom’s also fallen out, economically-speaking, for young men without college degrees:

Between 2000 and 2015, market hours worked fell by 203 hours per year (12 percent) for younger men ages 21-30, compared to a decline of 163 hours per year (8 percent) for men ages 31-55. . . . Not only have hours fallen, but there is a large and growing segment of this population that appears to be detached from the labor market. 15 percent of younger men, excluding full-time students, worked zero weeks over the prior year as of 2016. The comparable number in 2000 was only 8 percent.

Globalization, automation, immigration, and other related changes have resulted in stagnant wages for these 21- to 30-year-old men. Whatever work they can now find is neither particularly fulfilling nor terribly well paid.

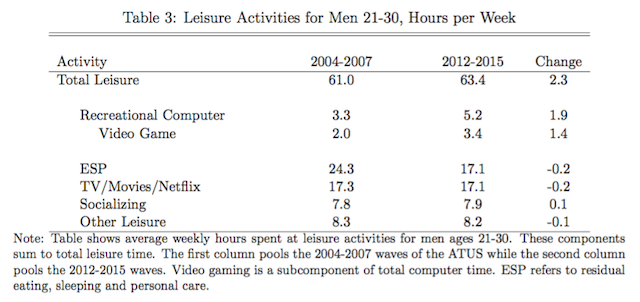

As these men work less, some are increasingly spending more time on the computer and playing video games, rather than earning paychecks. The study found that unemployed or out of the labor force young men spend about 530 hours a year, on average, on “recreational computer time, 60 percent of that spent playing video games.” Table 3 from the study, below, shows the average hours of leisure activities per week spent by these younger men between the two time periods.

Source: Aguiar, Bils, et al., "Leisure Luxuries and the Labor Supply of Men," NBER Working Paper No. 23552, June 2017

Furthermore, according to the study,

men ages 21-30 reduced their market work hours by 12 percent from 2000 to 2015, whereas the decline was only 8 percent for men ages 31-55. Our estimates suggest that technology growth for computer and gaming leisure can explain as much as three-quarters of that 4 percent greater decline for younger men.

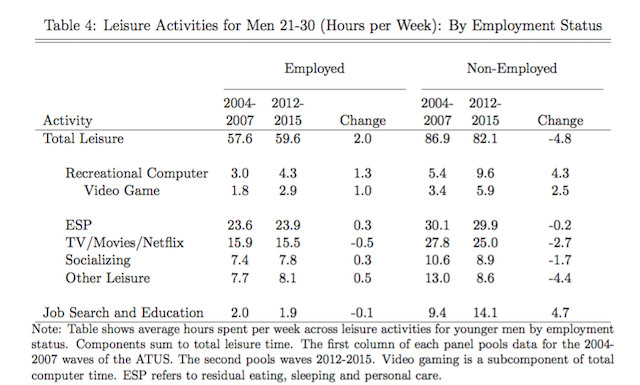

Table 4, below, shows the average number of leisure hours each week, according to men’s employment status.

Source: Aguiar, Bils, et al., "Leisure Luxuries and the Labor Supply of Men," NBER Working Paper No. 23552, June 2017

This update of the old “work hard, play hard” motto might be formulated as “play hard, work maybe.” And in contrast to older men, who report higher levels of unhappiness as they struggle to find meaningful work, these video-playing Millennials tell pollsters they are happy.

It’s hard for me to accept that survey data at face value, though. Is it possible to be truly happy when you are unemployed for an extended period in a nation that has always celebrated the Protestant Work Ethic? Given that American men have historically found purpose and a sense of identity in their honest labor, this would mark a seismic shift.

What does it mean that these non-working young men are content, or that they are seemingly turning to video games for a sense of accomplishment and community? What religious affiliation might have offered an older generation where relationships and a sense of belonging are concerned is less likely for this cohort, given that 35% of Millennials identify as religious “nones,” according to the Pew Research Center.

Beyond that, what will these men’s future economic prospects look like, since many are foregoing work experience in favor of living with their parents or other close relatives who subsidize them, sometimes out of Social Security checks? And what does it mean for the future of healthcare (long tied to employment) or the sustainability of social safety net programs like Social Security when able-bodied workers are not paying in during their prime working years?

The University of Rochester’s Mark Bils, one of the study’s four authors, replied to my question about these men’s economic prospects: "We don't know. That's an important question. I presume, like you, that earnings per hour will be hurt by the lack of labor force experience. But they can also potentially support themselves by working more or spending less."

That is undoubtedly true. Of course, such adjustments are easier if these men remain unattached. If they want to marry or start families, trade-offs could feel more costly.

At present, this remains a fairly theoretical concern. Of the men in this study, “Only 12 percent of non-working younger men are married, or live with a partner and a similarly small fraction report living in a household with a child.” A generation or two ago, things would have looked quite different. Men were forced to grow up more quickly by becoming husbands and fathers, with wives and young children who depended on them financially and otherwise.

Now, as The Atlantic reported, “the average age of first marriage in the United States is 27 for women and 29 for men [as of 2013], up from 23 for women and 26 for men in 1990 and 20 and 22 (!) in 1960.” This means more personal freedom for the average 20-something man. However, it also means that without work or a family to hold them accountable, these young men are free to “game” away their time. They are also increasingly unmoored from things, like marriage, that would have buoyed the hard and unpredictable lives of the blue collar men who came before them.

This matters, not only for economic reasons but also for the overall physical and psychological long-term health of the men involved. As Thomas B. Edsall recently noted in an article entitled “How Fear of Falling Explains the Love of Trump”:

The decline of marriage among less well-educated men serves only to accelerate the downward spiral. Single men lose out on the benefits of marriage, which include decreases in men’s risky behavior, such as binge drinking and drug use, a stronger commitment to work and an increase in time spent in home-oriented activities.

This potential spiral is a problem, especially when 49% of men without a college degree in the NBER study are living with a parent or close relative, rather than independently. Only 34% of women in that educational cohort have similar living arrangements. Considering that women are increasingly comfortable choosing to live and parent solo, even when men are financially secure, where does that leave these men?

Video games may be better than ever, but can they offer more long-term happiness than honest work, family, and in-person community—things that have traditionally proven meaningful to generations of men? It remains to be seen.

Melissa Langsam Braunstein, a former U.S. Department of State speechwriter, is now an independent writer in Washington, D.C. She frequently writes about culture, religion, and issues affecting families. She shares all of her writing on her website.

Editor’s Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.