Highlights

- The group with the highest probability of attending a selective college were students with fathers working full time and mothers working part time. Post This

- Students in two-parent families with mothers who did not work outside the home or mothers who worked only part time are more likely to get into elite colleges than those whose parents both work full time. Post This

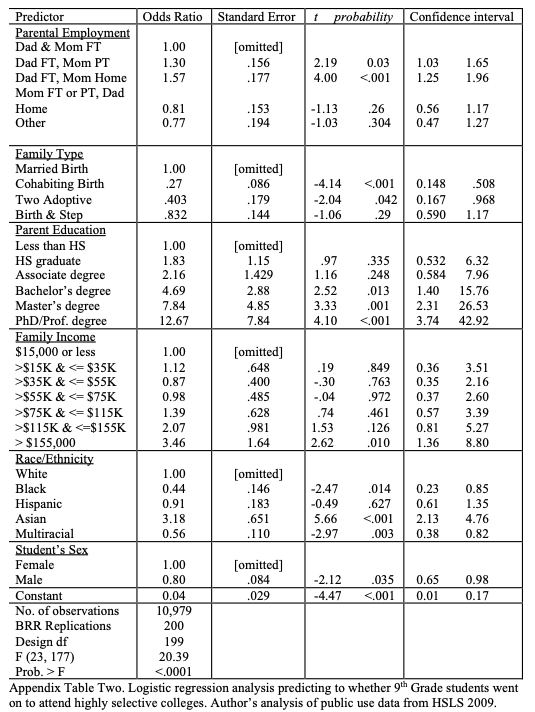

- More than 40% of freshman in two-parent families had fathers and mothers who both worked full-time. The second most-common arrangement was having a full-time working father and a stay-at-home mother. Post This

Getting into a selective college or university like Duke, Harvard, Princeton, or Stanford is exceedingly difficult. We know that one kind of resource—parental money—dramatically increases the odds that students attend selective schools like these, insofar as children from affluent homes are overrepresented at the likes of Yale and UCLA. But does another kind of resource—parental time—also matter for students’ educational attainment?

We consider this question by exploring different forms of the division of work and family. Do students go farther and get into better colleges when mothers stay at home or pursue work outside the home? When mothers work, does it make any difference if they work full time or part time? And how do students do in families where the mother is the sole wage earner?

One reason why students might achieve more if they have one parent who is the breadwinner and one who stays home is because of the benefits of the division of labor. Having one parent “specialize” in employment outside the home while the other specializes in childrearing enables each to devote more time, attention, and energy to their assigned area of responsibility, and do a better job at it, than when both must divide their efforts between competing tasks. Stay-at-home mothers can supervise their children’s studies and peer interactions more closely and participate more fully in school-related volunteer activities compared to mothers who are also employed outside the home. Meanwhile, fathers who are full-time breadwinners can put in more hours on the job and thus earn more and advance more rapidly—or so the argument goes.1

On the other hand, when both parents work full time outside the home, they can earn more money through their combined efforts, and thus have a higher standard of living and save more for college. But this financial argument is weakened by the need to spend money for substitute childcare, although the need is lessened as children grow older and are better able to care for themselves outside of school hours. An additional argument in favor of dual employment is that women are happier and more productive when they don’t have to postpone or give up their careers because of family responsibilities. And mothers who work outside the home serve as role models for daughters, encouraging them to apply themselves at school so they may achieve as well.

The argument in favor of one parent working full-time while the other works part-time is a compromise, or a “sweet spot” position. Families get some increased earnings combined with more time for at least one parent to supervise the child’s academic efforts and interactions with friends and classmates. Because men still earn more, on average, than women, this arrangement might work better when the parent who works part time is the mother, since mothers generally spend the greatest amount of time helping with and supervising children’s schoolwork.

As Alexandra Killewald and Hope Harvey have noted, much of the existing research on the consequences of maternal employment for children’s development and well-being has focused on employment during the child’s early years and has yielded mixed results. Less is known about the consequences of maternal employment for the health and achievement of adolescent and young adult children.2 Using rich longitudinal data from Norway, Haaland, Rege and Votruba found that maternal labor force participation had statistically significant and negative effects on years of education and labor market outcomes of adult children. The effects were modest in magnitude, however.3 Fan, Fang, and Markussen hypothesized that the dramatic rise in labor force participation by married women played a role in the narrowing and reversal of the gender gap in college attainment since the 1950s—where women are now besting men in college completion. They analyzed family-level data and trend statistics from Norway and the United States and found support for their contention.4

To examine the current relationship between parental employment and student college attendance, I utilized public-use data from a large, ongoing study being conducted by the U.S. Department of Education: the High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS 2009). This is a nationally representative, longitudinal study of more than 17,000 9th graders in 944 schools who are being followed throughout their high school and college years. The study focuses on understanding students' schooling and employment experiences from the beginning of high school into college and graduate school, the workforce, and beyond.

Employment Variations in Two-parent Families

When the students were in the 9th grade, 76% of them lived in two-parent families, including living with married or cohabiting birth parents, a birth parent and stepparent, or two adoptive parents. As shown in Figure 1 below, of these freshmen in two-parent families, more than 40% had fathers and mothers who both worked full-time (i.e., 35 hours or more per week). The second most-common arrangement was having a father who worked full time and a stay-at-home mother. The third was a father who worked full time and a mother who worked part time.

Income, Education, and Race Differences Among Parents

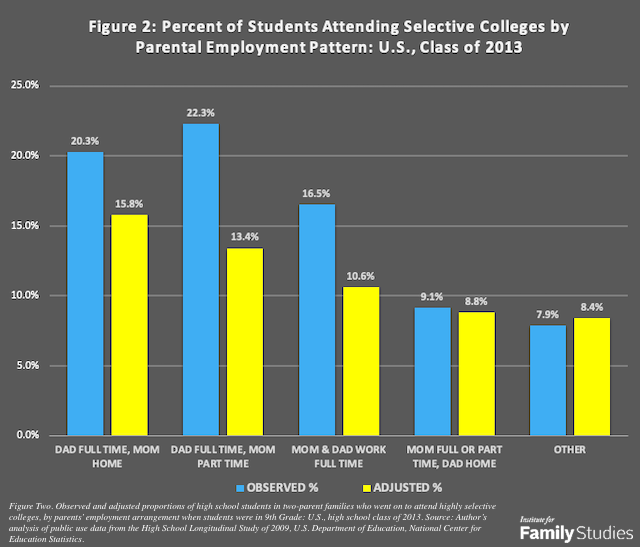

Couples who differ in whether and how much each parent works outside the home also differ in their income and education levels and racial and ethnic backgrounds. As these factors are related to student achievement, they should be taken into account when comparing the college trajectories of students by parental employment. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the different parental employment groups are summarized below and shown in more detail in Appendix Table 1 at the end of this brief.

Family income. Not surprisingly, average income was highest when both parents worked full time (median income around $80,000). But earnings were nearly as high when fathers worked full time and mothers worked part time. Average income was $20,000 less in families where fathers worked full time and mothers were not employed. And earnings were still lower when the mother was the sole wage earner or when parents had other employment combinations.

Parent education. Income disparities were partly attributable to parent education differences. A 55% majority of students whose fathers worked full time and mothers worked part time had at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree or more, whereas a 52% majority of students whose parents both worked full time had parents with associate degrees or less. Parent education levels were also not as elevated for students with breadwinner fathers and stay-at-home mothers. Education levels were still lower in families where the mother was the sole wage earner: in nearly half of these families, the more educated parent had a high school diploma or less. And in families with other employment arrangements, a majority of parents had high school diplomas or less.

Race and ethnicity. Employment groups also differed in racial and ethnic composition. Three-quarters of students in families where fathers worked full time and mothers worked part time were white or Asian, as were two-thirds of students in families where both parents worked full time. By contrast, less than 60% were white or Asian in families where the father was the breadwinner and the mother stayed home, and only half in families where the mother was the sole earner. The majority of students were Hispanic, multiracial, or black in families with other parental employment arrangements.

Relating Parental Employment to Student College Attendance

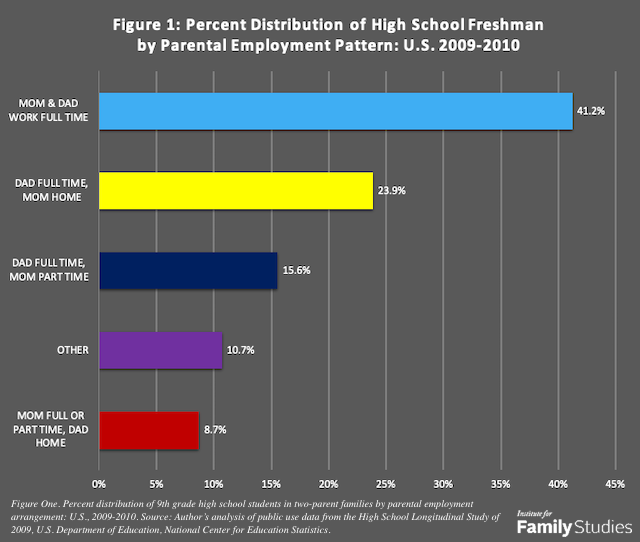

There was a significant relationship between parental employment when students were in 9th grade and the probability that they would go on to be accepted by and attend a highly-selective college. (“Highly-selective colleges” are those whose first-year students’ test scores placed the schools in the top fifth of baccalaureate-granting institutions). As shown in Figure 2, the group with the highest probability of attending a selective college were students with fathers working full time and mothers working part time. This proportion was significantly higher than the one for students whose parents both worked full time, as well as higher than those whose mothers worked while the father did not, and those students with other parental employment patterns. It was not significantly different from the proportion for students with a full-time working father and a stay-at-home mother.

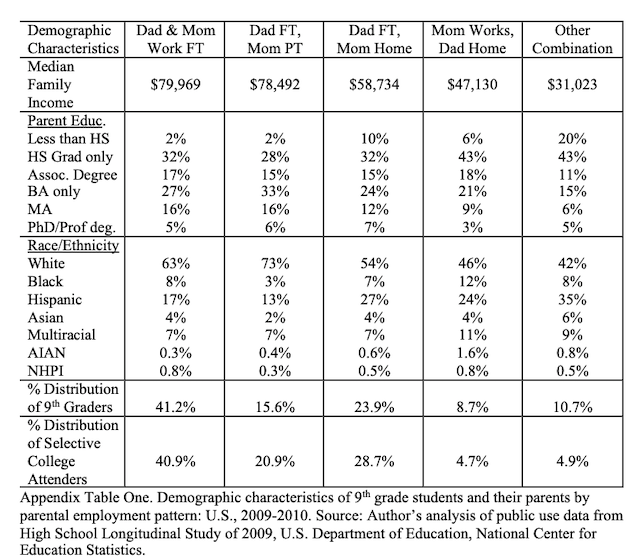

The picture changed somewhat when I used logistic regression analysis to adjust the parental employment-college attendance relationship for differences across the employment groups in parent education, family income, racial composition, and family type, as well as for student sex (results are shown in Appendix Table 2). The yellow bars in Figure 2 above show the regression-adjusted proportions of students attending selective colleges when the income and education levels and racial composition of the parental employment groups are equalized by setting them at overall mean levels.

After adjustment for demographic and socioeconomic factors, the group most likely to attend selective colleges were students in families with a breadwinner father and a stay-at-home mother. The odds that students in this group would attend selective colleges were significantly higher than those for families where both parents worked full time (odds ratio of 1.57). Students whose fathers worked full time and mothers worked part time also had significantly better odds of attending selective colleges. The breadwinner-father/stay-at-home mother group and the full-time working father/part-time working mother group did not differ significantly from each other. Students whose mothers were the sole wage earners or whose parents had other employment arrangements had lower odds of attending selective colleges.

Parental Employment Matters for College Attendance

To summarize the results of this investigation, let us return to the questions posed at the beginning of this article:

- Does parental employment matter for students’ educational attainment? Yes, it does, although not as much as other, related factors, such as parent education, family income, family structure, and the racial and ethnic background of the family.

- Do students go farther and get into better colleges with stay-at-home mothers, or when both parents work outside the home? Students are more likely to be accepted by and to attend highly competitive colleges when their mothers are at home than when their mothers and fathers both work full time.

- When mothers work outside the home, does it make any difference if they work full or part time? Yes, it does. Students with mothers who work part time are more likely to attend selective colleges than those with mothers (and fathers) who work full time.

- How do students fare in families where the mother is the sole wage earner? Students in families where the mother is the sole wage earner are less likely to attend selective colleges. The same holds true for students whose parents have other employment arrangements, such as both working part time or neither working for pay.5

Nicholas Zill is a research psychologist and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. He directed the National Survey of Children, a longitudinal study that produced widely cited findings on children’s life experiences and adjustment following parental divorce.

1. Becker, Gary S. A Treatise on the Family. Enlarged Edition (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009).

2. Killewald, A., & Harvey, H. (2016). "The effect of maternal employment experiences on adolescent outcomes." Presentation at the 2016 Population Association of America Annual Meeting. Extended abstract available from killewald@fas.harvard.edu. See also: Killewald, A., Zhuo, X., "U.S. Mothers’ Long-Term Employment Patterns," Demography 56, 285–320 (2019).

3. Haaland, V.F., Rege, M., & Votruba, M. (2013). "Nobody home: The effect of maternal labor force participation on long-term child outcomes." CESifo Working Paper No. 4495. Norway: Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute.

4. Fan, X., Fang, H. & Markussen, S. (2017). "Mothers’ employment, parental absence and children’s educational gender gap." Sydney, Australia: ARC CEPAR, University of New South Wales.

5. The above conclusions are based on parental employment patterns observed when the students were in the first year of high school. They assume that these patterns reflect earlier employment arrangements, when the students were younger, as well. The data set analyzed here did not include explicit information about those earlier arrangements. The findings are consistent with those of Haaland, Rege and Votruba (op. cit.), however, who used Norwegian data on employment throughout childhood. Using data from the Labor Department’s 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Killewald and Zhuo (op. cit.) have documented five common employment patterns of American mothers over the first 18 years of childhood. Their results support studying parental employment as a long-term pattern. The present findings should be replicated and extended with longitudinal data that permit such an approach.

Appendix Tables

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics

Table 2: Logistic Regression Analysis