Highlights

- Among adults who desire children but are still looking for the right spouse or partner, 42% say that they are willing to have children on their own, while 58% say no. Post This

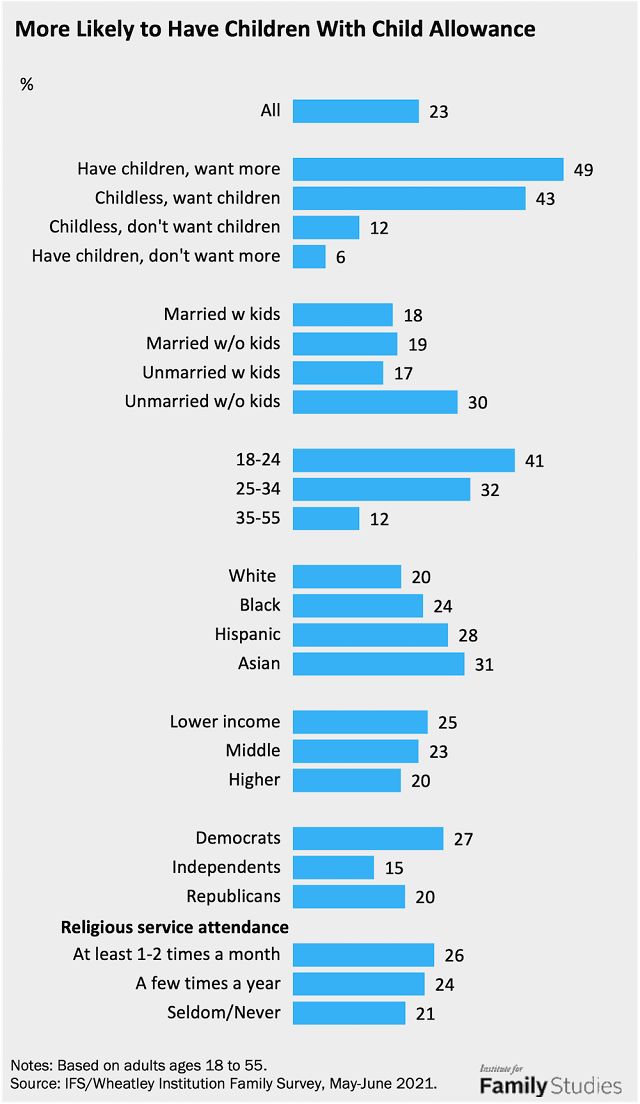

- Close to half of parents who want more children (49%) say the child allowance will make them more likely to have another child, so do 43% of non-parents who desire children. Post This

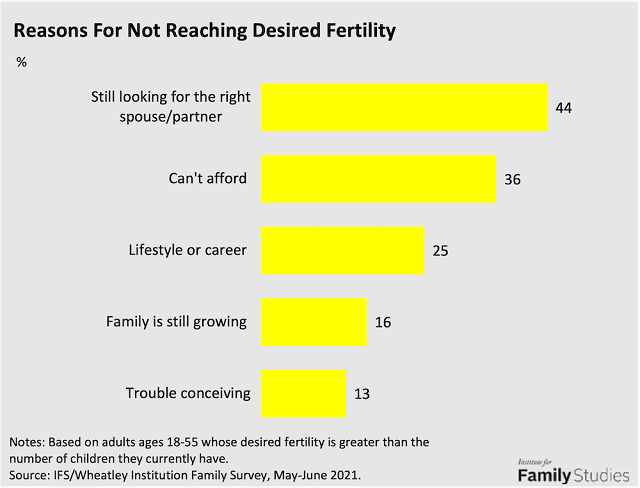

- “I am still looking for the right spouse/partner” tops the list of reasons cited by respondents for not having the number of children they desire. Post This

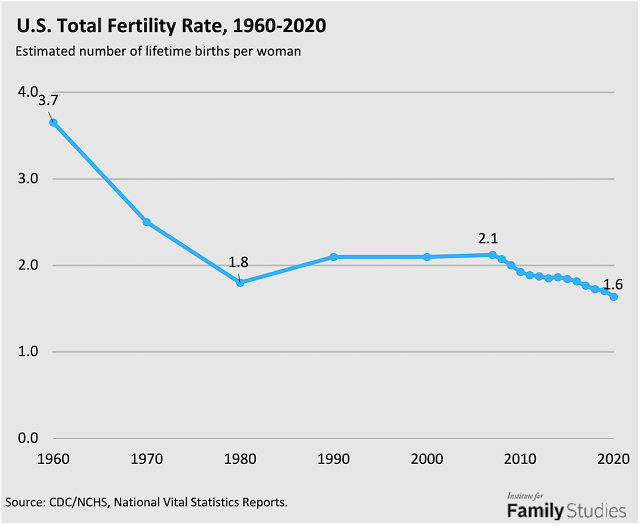

The birth rate in the U.S. fell to a record low in 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic. On average, an American woman is expected to have about 1.6 children in her lifetime. This is well below the population replacement level (2.1 children per woman). The pandemic has also put a damper on people’s desire to have children, with more American adults ages 55 and younger saying their fertility desire has decreased since COVID-19.

The downward trend for U.S. fertility started long before the pandemic. The fertility rate hovered around the replacement level during most of 1990s and 2000s and started to drop in 2008, in the wake of the Great Recession. It has not returned to the pre-recession level since. Recent research by Melissa Kearney and colleagues suggests that demographic, economic, or policy changes have little to do with this decline. Meanwhile, the marriage rate in the U.S. also hit an all-time low. For every 1,000 unmarried adults in 2019, only 33 got married. The number was 48 just about two decades ago in 2000.

The decline of marriage goes hand in hand with falling fertility rates, simply because married women have a much higher fertility rate than unmarried women. In 2020, the birth rate was 81 per 1,000 married women ages 15-44, but just 39 per 1000 unmarried women of the same age. When fewer women are married, fewer babies are born. In fact, about half of the decline in fertility since 2008 can be attributed to changes in marital composition, according to an analysis by Lyman Stone. Simply put, other things being equal, if the marriage rate had remained the same since 2008, the U.S. fertility rate would have been around replacement level.

Data from a recent YouGov survey by the Institute for Family Studies and Wheatley Institution echoes this pattern between marriage and fertility, as I show in a new IFS research brief. Among the reasons cited by respondents for not having the number of children they desire, “I am still looking for the right spouse/partner” tops the list. Fully 44% of Americans ages 18-55 who desire (more) children cite this reason, compared with 36% who cite financial reasons, and 25% who point to their lifestyle and career as hurdles to having children.

Finding the right spouse/partner is especially important among childless adults. A majority of childless adults who want children (60%) cite this as a reason for their unmet fertility desires, compared with 16% of parents who want more children. More than one-third of childless adults (37%) also say that they can’t afford to have a child, and 28% say their preferred lifestyle or career would be difficult with children. For parents who want more children, financial reasons are the main hurdle to reaching their desired number of children (36%), followed by their family is still growing (33%), and lifestyle or career (21%), as well as having trouble conceiving (20%).

Similarly, still looking for the right spouse/partner is the top reason why unmarried adults are not having their ideal number of children. More than 6-in-10 (64%) cite it. Financial reasons come in as a distant second, with some 38% of unmarried adults saying they can’t afford to have (more) children. For married adults whose fertility desire is not met, more than one-third (36%) say their family is growing, and 34% say they can’t afford to have (more) children. One-in-four married adults also cite “having trouble conceiving” as a reason why their family is not growing as much as they hope. (See Appendix A).

Men are much more likely than women to cite lack of a partner as the reason (52% vs. 36%) why they don’t have the number of children they desire. The gap is smaller among childless men and women: 63% of childless men who want children say they are still looking for the right spouse/partner, so do 55% of women in the same situation.

The reasons why people don’t have their ideal number of children also vary by religious attendance. Adults who seldom or never attend religious services are much more likely than those who attend services regularly to pick “still looking for the right spouse/partner” as a reason (50% vs. 34%). Compared with their religious peers, non-religious adults with unmet fertility desires are also more likely to cite finance and lifestyle or career as reasons why they haven’t had the number of children they want. (See Appendix A).

Compared with Republicans, Democrats who desire more children are much more likely to cite financial reasons as an obstacle (41% vs. 29%), as well as that their preferred lifestyle or career would be difficult for having children (29% vs. 20%). Meanwhile, Democrats overall are more likely than Republicans to say that government assistance, such as a child allowance, will boost their chance to have children (27% vs. 20%).

Other key findings from the survey include:

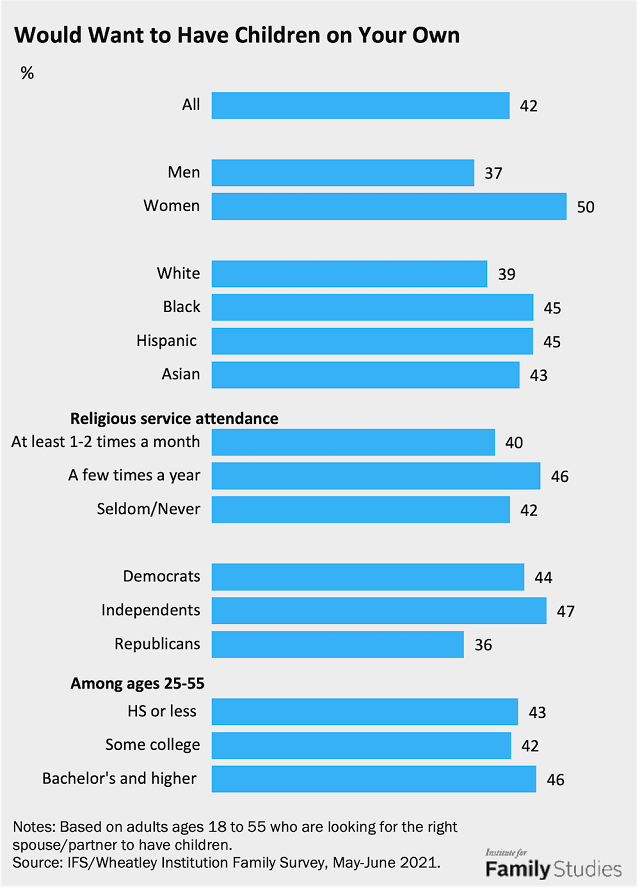

- Having a child on their own is NOT an option for many Americans. Among adults ages 18-55 who desire children but are still looking for the right spouse or partner, 42% say that they are willing to have children on their own even if they can’t find the right partner, while 58% say no.

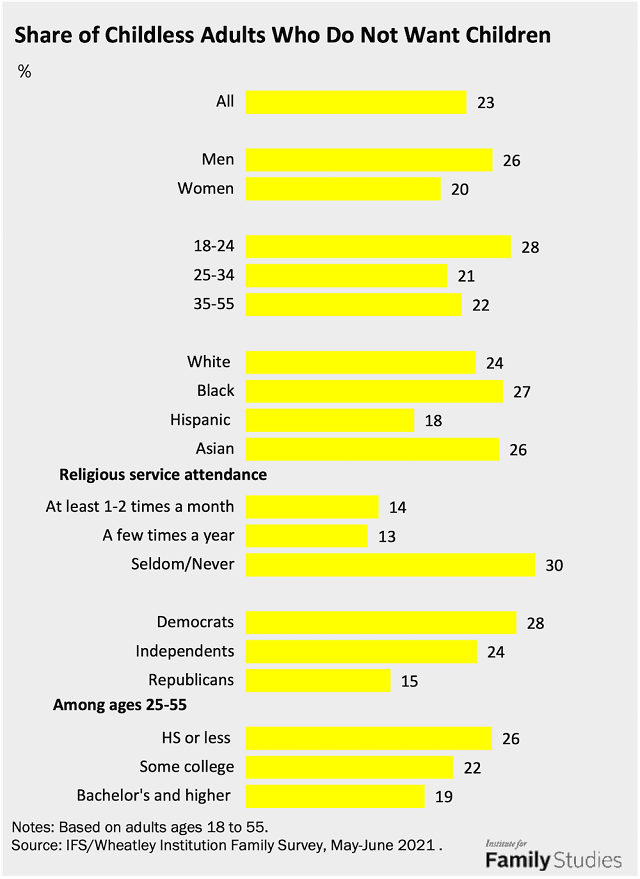

- The group saying no to parenthood is growing. Close to a quarter of adults (23%) are currently childless and say they do not hope or desire to have a child someday. Men, younger adults, and adults without a college education are more likely to be in this group, so are Democrats and non-religious Americans.

- Government assistance will likely boost fertility in the U.S. Nearly half of parents who desire more children (49%) and 43% of childless adults who want children say that a child allowance, such as $300 per child per month, will make them more likely to have children. Even among the childless adults who desire no children, 12% indicate that their likelihood of having a child will increase if a child allowance were provided.

- The child allowance gets stronger responses from Democrats and religious Americans, the two groups that do not always overlap. Some 27% of Democrats say that a child allowance will make them more likely to have children, as do 26% of adults who attend religious services on a regular basis. In comparison, this government intervention could be less effective for Republicans, Independents, as well as non-religious Americans.

Having a Child on Your Own is NOT an Option for Many

What happens if the right spouse or partner never arrives? To find out the importance of marriage to childbearing, the survey also asked a follow-up question to those who are still looking for the right partner: “Would you want to have children on your own even if you do not get married/have a partner?” About 4-in-10 respondents (42%) say yes, and a majority say no.

Answers to this question differ by gender. Women who want children but haven’t found a partner are much more likely to say yes than men in the same situation. Half of women say they want children on their own even without a spouse or partner, while only 37% of men say the same. Non-white respondents are slightly more likely than whites to say they are willing to have a child on their own. College graduates also show a slightly higher willingness to have a child on their own even if they don’t find a spouse or partner.

There is also a difference by party ID. Among Democrats and Independents who are still looking for the right partner, 45% say they are willing to have children on their own regardless; the share among Republicans is lower (36%).

Public opinion on non-marital childbearing, especially single women having children, has been much more tolerant over the years. In this same survey, more than 7-in-10 Americans ages 18-55 (71%) disagree with the statement that it is morally wrong for single women to have children on their own. The share among adults who are looking for the right spouse/partner to have children is similar (72%). But when it comes to the realities of having children on their own, most Americans who long to be parents hesitate to take that action.

Saying No to Parenthood

It is important to note that not everyone wants to have children. The share of childless adults who do not expect to have children has been rising in recent years. Among Americans ages 18-55, 23% are childless and say they do not hope or desire to have a child someday, according to the IFS/Wheatley survey. Men are more likely than women to be in this group. Some 26% of men ages 18-55 are childless and do not desire a child someday, compared with 20% of women.

The pattern also varies by a few other demographic factors. Young adults under age 25 are much more likely to say no to parenthood than those who are older. Adults with lower levels of education are also more likely to say they don’t expect to have children. Some 26% of adults with high school or less education do not long to be parents, compared with 19% of those with a college degree. Finally, the share of adults who are childless and do not want kids is lowest among Hispanic adults. Only 18% of Hispanic adults ages 55 or younger are childless and do not wish to have children; the share is 27% among blacks, 26% among Asians, and 24% among whites.

The differences by religion and party ID are large. Fully 30% of non-religious Americans reject parenthood, compared with 14% of their peers who attend religious services regularly, and a similar share among those who attend religious services a few times a year. Meanwhile, childless Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to say they do not plan to have children (28% vs. 15%).

The desire or lack of desire for having children may not match the action down the road for some individuals. As situations change, people’s attitudes may change. But recognizing attitudes toward fertility is important for researchers and policy makers who monitor population growth in the U.S. If the current trend holds, the U.S. will soon see a sustained decline in birth rates. Challenges that come with low fertility, such as a shrinking labor force, slow economic growth, and increased government budget on an aging population, will be issues that we face.

Will a Child Allowance Spur Childbearing?

Low fertility is a global phenomenon, with half of the global populaton living in countries where the fertility rate is below the replacement level. While many developed countries have policies that aim to support families and promote fertility, the U.S. is an exception. In this survey, we asked a hypothetical question, “If the government paid parents a child allowance, such as $300 per child per month, would that make you more likely to have a (another) child?” Among adults ages 18-55, more than 1-in-5 (23%) say yes.

The child allowance is especially likely to induce childbearing among those who want to have children. Close to half of parents who want more children (49%) say the child allowance will make them more likely to have another child, so do 43% of non-parents who desire children. Even among those who are childless and don’t plan to have children, 12% indicate that their likelyhood of having a child will increase if a child allowance were provided.

Compared with married adults, unmarried, childess adults are much more likely to say that the child allowance will increase their chance to become parents (30% vs. 18%). In contrast, this child allowance is not particularly effective among unmarried adults who already have children. Only 17% say the child allowance will make them more likely to have children.

Younger adults are more responsive to the idea of government assistance. Large shares of younger adults under age 25 (41%) say that the child allowance will help, compared with 12% of adults ages 35 to 55.

The response to government assistance also differs by race and ethnicity. Asian Amerians (31%) and Hispanic Americans (28%) are more likely than whites (20%) and blacks (24%) to say that the child allowance will make them more likely to have children.

The child allowance also gets stronger reponses from Democrats and religious Americans, the two groups that do not always overlap. Some 27% of Democrats say that the child allowance will make them more likely to have children, so do 26% of adults who attend religious services on a regular basis. In comparison, the government intervention could be less effective for Republicans, Independents, and non-religious Americans.

Among the adults who say that they are still looking for the right person to have children with, 40% also indicate that this child allowance will help them achieve their fertility goals. For the subset of respondents who are willing to have children on their own, 57% say that the child allowance will help. Other factors such as education and gender are not strongly related to the response to the government policy.

In summary, the decline in U.S. fertility is closely related to the decline in marriage. Finding the right partner with whom to have children trumps economic reasons as the major hurdle for many adults who desire to have a family. Even though public policies may not be able to help individuals find the right spouse, government assistance, such as a child allowance, does seem to boost people’s likelihood of having more children.

Wendy Wang is director of research at the Institute for Family Studies. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other venues.

Download the full IFS research brief, which includes more figures and information on the survey.