Highlights

Washington, D.C., is a wonderful city in which to be young. That is to say, it is wonderful for the sort of young person who has a driver’s license, a credit card, and a W-4. Sushi bars and bistros beckon from every corner. Receptions and social gatherings offer the tantalizing possibility of proximity to power. In a recent study by the job website “Career Bliss,” DC was found to be the nation’s third happiest city for young professionals. For the ambitious and upwardly mobile, Washington is the land of milk, honey, and glittering opportunity.

For the diapered, lunch-box-toting or pig-tailed young, the story is quite different. More than half of babies in D.C. are born out of wedlock. Nearly a third of children live at or below the poverty line. The public schools consistently rank among the nation’s worst. All in all, Washington is a miserable city in which to be a child.

The capital is not unique. From sea to shining sea, urban “kiddie deserts” have become a haven for the childless rich, a trap for the poor, and a no-man’s land for middle-income families. Joel Kotkin and Ali Modarres have recently described this phenomenon in “The Childless City,” explaining that rising rents and rising crime emptied American cities of middle-class families in the decades following the Second World War. Literally and figuratively, parents went in search of greener pastures. Affordable housing, low crime, better schools, and open space could be found in small towns and suburbs.

Urban “kiddie deserts” have become a haven for the childless rich, a trap for the poor, and a no-man’s land for middle-income families.

Today urban America is a story of two classes. The childless elite and the struggling poor live side by side but are not on speaking terms. Meanwhile a functional family culture is all but extinct, and increasingly, Alan Kotlowitz’s declaration that “there are no children here” is becoming a literal reality.

Kotkin and Modarres worry about the sustainability of this urban model. Without the ability to raise functional citizens, it is difficult for a city to maintain its economic and cultural vitality, as can already be seen in failing cities like Detroit. But the phenomenon of the childless city should also be disquieting to anyone who is interested in marriage and family formation.

Today’s educated young singles lead an unnaturally child-free existence. It begins in college, and continues in urban kiddie deserts where they are surrounded by fellow singles, developing a dynamic social life that is completely free of car seats and parent-teacher conferences. Young people have always enjoyed their liberty, and these child-free environments are tailor-made to gratify their desires for entertainment, social interaction, professional advancement and, of course, sex. But there is nothing in this world to tell them when it is time to move on. Perhaps unsurprisingly, some of them never do.

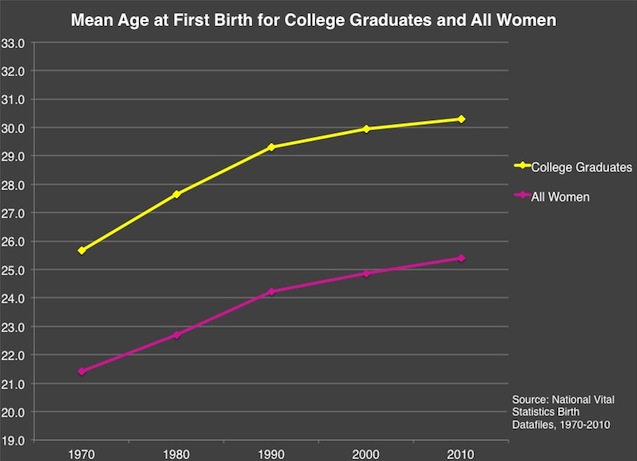

It is well known by now that birth rates are falling across the developed world as the voluntarily “child-free” life becomes a respected and even celebrated alternative to parenthood. Not coincidentally, marriage rates are also declining, particularly in cities. A 2009 Pew study found that Washington, D.C., has the lowest marriage rates in the country: an incredible 77% of Washington’s women were unmarried at the time of the study. Those who do tie the knot tend to do so later in life, and then (especially if they’re college graduates) they may wait a few more years to have a child. Thus the average college-educated woman gets married at around age 27 and has her first baby around age 30, after roughly 12 years of living child-free. Just forty years ago, she would have been closer to 23 and 26 years old as she completed those milestones.

Historically, young adulthood—that is, the late teens and early twenties—is the phase of life in which people begin having children. For us, it has become the phase in which children are neither seen nor heard. Young people shape their expectations in harmony with what they see around them, so it is important that they see families. When people frequently make it into their thirties without ever changing a diaper, it spells trouble for the national birth rate.

On a more human level, it means a rocky road for those who do take the plunge into family life. Raising kids has never been easy, but it is much harder for young people who have few domestic skills and no clear idea of what to expect. Harrowing accounts of new parenthood appear regularly in publications like the Huffington Post, confirming what any observer of youth culture would naturally expect. After years of projecting competence in competitive environments, young women feel lonely and overwhelmed by the challenges of dealing with a needy infant and adapting to a completely new social situation. Postpartum depression has become a major problem in America both for moms and for dads.

Raising kids is much harder for young people who have few domestic skills and no idea what to expect.

What can we do at this juncture? We can make families more visible. Universities could begin the process by sponsoring more activities for families with children. Even if they don’t have children of their own, students would benefit from seeing the children of faculty, staff, or local residents at their celebrations and sporting events. Married student housing should be centrally located on campus. Playgrounds should be installed in those beautiful, lush campus lawns.

Bringing families back to the cities is more challenging, but as Kotkin and Modarres point out, we do know what it takes. Build parks. Improve schools. Keep crime under control. Welcome middle-class families back to U.S. cities. Young Americans need to see family life as the fulfillment, not as an interruption, of the life that they want to have. When they do, our nation can recover the human resources that it needs to thrive.

Rachel Lu teaches philosophy at the University of St. Thomas.