Highlights

- The Social Genome Model...corroborates that family structure is one significant reason children born [to unmarried parents] have lower rates of upward intergenerational mobility. Post This

- We find that children whose parents are married when they are born do better in life than those whose parents were not married when they were born. Post This

- We should be clear-eyed about the negative effects of single parenthood on children. Post This

The impact of family structure, particularly marriage, on children’s well-being has always been a somewhat controversial topic, but that doesn’t make it any less salient. The share of adults who are married has declined from about two-thirds in 1970 to one half in 2023.1 The share of births to unmarried women has increased from about 11% in 1970 to 40% in 2022.2 Some predict that approximately one-third of Gen Z will never marry. Marriage rates are particularly low for those without a college degree.3

Some researchers4 have made the case that marriage doesn’t matter much, while others have argued that marriage does matter. This raises the question—who is right? How much difference does marriage make in determining children’s later-in life success?

The short answer is that marriage still matters. And depending on what metric you examine, marriage can matter a lot.

The basic reason is simple: two is better than one. Children raised by married parents do better than children raised by single parents because married parents tend to have more time, money, and emotional bandwidth to invest in raising their children. Research indicates that growing up in fatherless households negatively affects boys, in particular.5

There is a long literature demonstrating that, on average, growing up in a married-parent household is better for children’s later life outcomes. This is the conclusion reached by multiple well-respected researchers, including Isabel Sawhill in Generation Unbound (2014); David Ribar in “Why Marriage Matters for Child Wellbeing” (2015); Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill in “The Decline of the American Family” (2016); Melissa Kearney in The Two Parent Privilege (2023); and Brad Wilcox in Get Married (2024).

Our latest research adds further support to this literature. It reports on an analysis using the Social Genome Model, a life-cycle model created by the Brookings Institution, the Urban Institute, and Child Trends to explore the effects of a variety of circumstances or policies on child well-being over the life course.

The Social Genome Model

The Social Genome Model is a microsimulation model that tracks children’s progress through multiple life stages, using a set of age-appropriate standards of success measured at the end of each life stage to determine whether they are “on track” or not.6 The benchmarks for success are common-sense metrics that empirical evidence shows to be predictive of success later in life. A child is considered successful at the end of elementary school, for example, if he or she has mastered basic math and reading skills, has acquired the behavioral competencies that are predictive of later success, has a strong relationship with his or her parent(s), and is in good health. To be considered successful, or “on track” at a given life stage, an individual must successfully clear the benchmark for all indicators of success at that stage.7

The model uses data from three nationally representative longitudinal surveys: The Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), The Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K), and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth—1997 (NLSY-97) to analyze the life trajectories of children in the U.S. from birth to adulthood. The same individuals were surveyed in early adolescence around age 15 in the NSLY97 and ECLS-K, and this period of overlap allows us to create a matched panel dataset which was produced by linking the ECLS-K and NLSY-97 and was also informed by data from the ECLS-B.8

Results

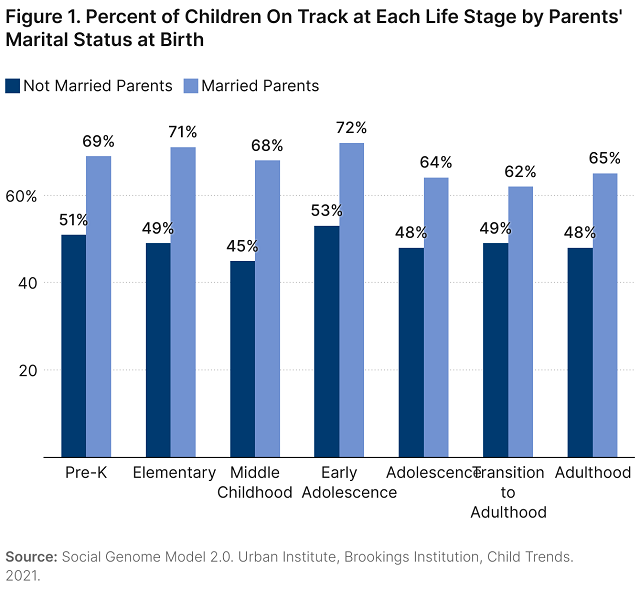

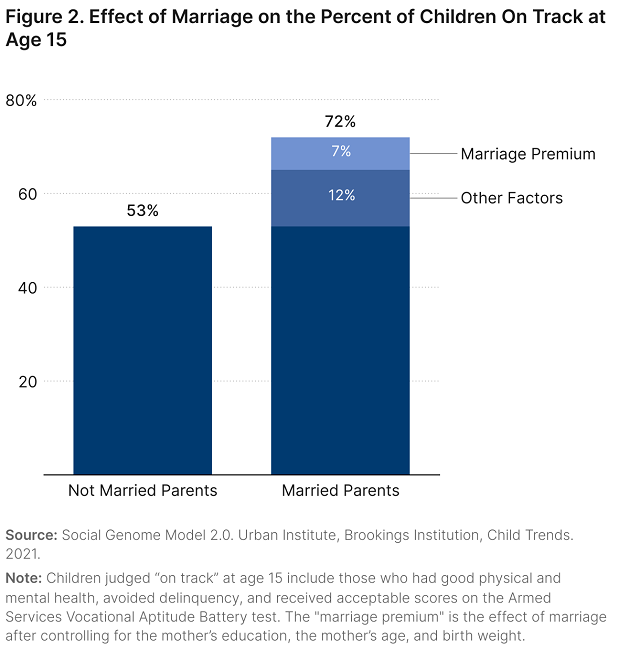

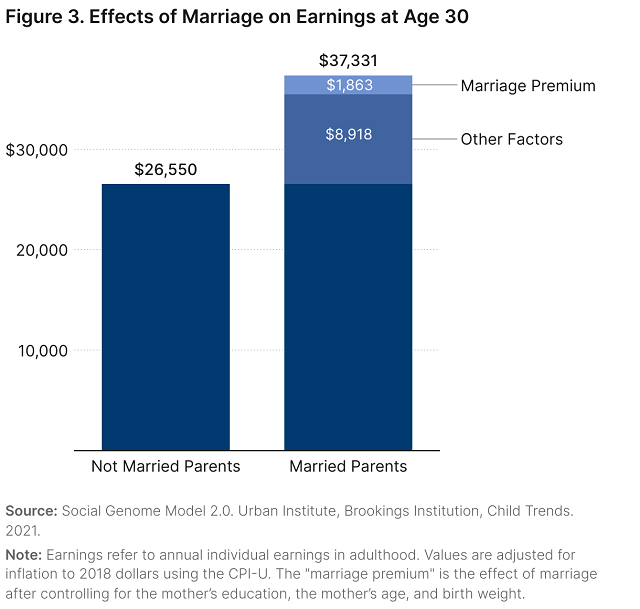

In brief, we find that children whose parents are married when they are born do better in life than those whose parents were not married when they were born. Children born to married parents are significantly more likely to be “on track” at every life stage than children who are born to unmarried parents. However, some of these effects are the result of marriage being more likely among better-educated parents, women who delay childbearing until they are older rather than having children as teens or in their early twenties, or other factors. After we control for these variables, the effects are not as large but still very significant.

The effects of marriage are greatest during the elementary school, middle childhood, and early adolescence stages of life. Children whose parents are married when they are born have better life outcomes than children who were born to unmarried parents even after controlling for the mother’s education and age, birth weight, and doing separate analyses for race and gender.

To provide a few examples that illustrate how big of a difference marriage makes, after controlling for these other factors, being born to married parents increases the share of children who are “on track” at age 15 by 7 percentage points or by 13 percent.

Similarly, after controlling for these other factors, being born to married parents increases a child’s individual earnings at age 30 by an average of about $1,900, or by 7 percent.

After controlling for other factors, being born to married parents increases the share of children with basic reading and math skills at the end of elementary school by 8 percent. It increases the share of children scoring above the cutoff score for the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) test by 6 percent.9 It increases the share of children who earn a high school degree by 2 percent. It increases the share of children who earn a college degree by 14 percent.

Comparing various subgroups, the data show that children born to married parents do better, on average, across all demographic groups broken down by gender and race.

If we average the percent increase in the share of children “on track” enjoyed by children born to married parents across every life stage, we find that the average percent increase across all life stages is greater for Blacks (13%) than for whites (9%) and Hispanics (9%). Among all racial groups considered (white, Hispanic, and Black), children are most affected by marriage during elementary school, middle childhood, early adolescence, and the transition to adulthood.

If we disaggregate by sex, males, on average, are more affected by marriage than females during the early stages of life, while females are more affected by marriage than males in later stages of life.

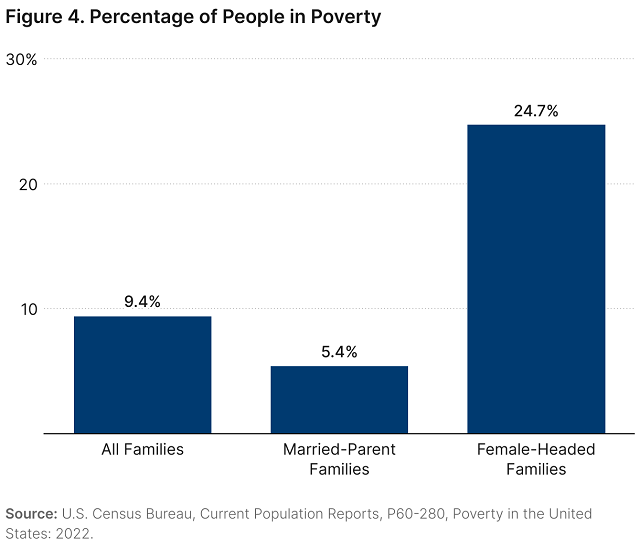

The finding that children who are born to married parents tend to enjoy better life outcomes is consistent with existing research that has established that children who grow up in two-parent families are more likely to graduate from college and work and are less likely to have children young, be depressed, be convicted for committing a crime, or end up poor as adults, on average.10 The child poverty rate is about five times greater for children living in female-headed families than married-couple families.11 Earlier, Sawhill and Thomas found that if the share of children living in single-parent families had stayed at the 1970 level, and we married single parents to men who were well-matched to the women in question, the current child poverty rate would be reduced by approximately one-fifth.12

What does the Social Genome Model contribute to this existing literature? It demonstrates that there are long-term effects for children who are born to unmarried parents and corroborates that family structure is one significant reason children born into these types of families have lower rates of upward intergenerational mobility than other children. These findings accord with research by Raj Chetty and others who have found that family structure is one of the strongest indicators of relative intergenerational mobility.13

The estimates from the Social Genome Model produced above are plausible but could be biased because of our inability to control for some variables that may be correlated with marriage and because the matching process needed to create the data lends a downward bias to the estimates. That said, our view is that this downward bias related to matching outweighs any potential upward bias, making these conservative estimates of the effects of marriage. It should also be stressed that there are plenty of children born to single parents who do very well.

Implications

What should we make of these findings?

First, we should stop pretending family structure doesn’t matter. It is difficult to put aside the cultural and moralizing debates surrounding this issue, but facts are facts, and the data show single parenthood does hamper children’s later-in-life outcomes.

Given these findings, some argue we should endeavor to revive marriage. We are skeptical of the government’s ability to reverse declines in marriage rates, and most programs which have tried to do so have been unsuccessful. Brad Wilcox argues marriage can be saved if well-educated Americans who are “walking the walk” by still getting married and reaping its benefits begin “talking the talk” by promulgating its benefits to others. Perhaps Wilcox is right, and marriage can be revived with the help of faith-based efforts or social marketing campaigns.

It is more likely, however, that the cultural genie is out of the bottle and marriage rates will remain low.14 We can’t go back to the 1950s, and in many ways that is a good thing. Women are now less financially dependent on their husbands and less confined to unhappy or sometimes abusive marriages. Society will likely need to explore and experiment with new types of living arrangements, and this is already happening.15 Cohabitation between unmarried partners has increased in recent years. It remains to be seen whether these types of living arrangements can offer the same benefits to children as marriage. We believe that what matters is not marriage per se but commitment and mutually shared responsibility, especially if a child is involved. Whether cohabitation can provide these is still an open question, but there are reasons to worry, since cohabitation arrangements tend to be less stable than marriage.16

In our view, we can take a balanced approach. That would involve giving help to children and moms in existing single-parent families by providing access to quality child care, health care, and expanded tax credits (especially the EITC). It would also involve providing funding for education, job training, and mentoring programs for young adults.

On the other hand, we should be clear-eyed about the negative effects of single parenthood on children. Accordingly, we should discourage the next generation from believing that raising children alone is a good idea unless the parent involved intentionally chooses to do so. Some parents do choose to raise children on their own, but most do not. For example, over 70% of pregnancies and 60% of births to unmarried women under the age of 30 are unintended.17 Rates of unplanned pregnancies are especially high among low-income and minority women.18

With access to better family planning, the unplanned births that are a major cause of unintentional single parenthood can be avoided. Young women should be able to choose whether, when, and with whom to have and raise a child. Whereas the old societal norm was not to have children outside of marriage, the new norm should be not to have children until both parents are ready to raise them and are committed to doing so, ideally together in a stable and lasting union.

Isabel Sawhill is a Senior Fellow Emeritus at the Brookings Institution. Kai Smith is a Research Assistant at the Brookings Institution.

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank Morgan Welch, a former Senior Research Assistant at the Brookings Institution, for contributing to the analysis in this brief.

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed in this research brief are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies

1. U.S. Census Bureau, "Historical Marital Status Tables," Table MS-1.

2. Stephanie Ventura, “Births to Unmarried Mothers: United States, 1980–92." National Vital Statistics Reports 21, no. 53 (June 1995); Michelle Osterman et al., "Births: Final Data for 2022," National Vital Statistics Reports 73, no. 2 (April 2024): 5.

3. Shelly Lundberg et al. "Family Inequality: Diverging Patterns in Marriage, Cohabitation, and Childbearing." Journal of Economic Perspectives 30, no 2 (Spring 2016): 79-102.

4. Patricia Cohen, "How to Live in a World Where Marriage Is in Decline," The Atlantic, June 4, 2013; David Brady et al., " Single Mothers Are Not the Problem," New York Times, February 10, 2018; Christina Cross, "The Myth of the Two-Parent Home," New York Times, December 9, 2019.

5. Marianne Bertrand and Jessica Pan, "The Trouble with Boys: Social Influences and the Gender Gap in Disruptive Behavior," NBER Working Paper 17541 (2011); Raj Chetty et al., "Childhood Environment and Gender Gaps in Adulthood," NBER Working Paper 21936 (2016).

6. There have been several different versions of the Social Genome Model, including version 1.0 which was created at Brookings and versions 2.0 and 2.1 created by the Urban Institute and Child Trends. This analysis is based on version 2.0.

7. For a full description of the Social Genome Model, including more details on the measures of success used at each life stage and the corresponding benchmarks individuals must meet to be considered “on track,” see Kevin Werner et al., “Social Genome Model 2.0: Technical Documentation and Users Guide,” Urban Institute, Brookings Institution, Child Trends, February 2021; Gregory Acs et al., “Identifying Pathways for Upward Mobility,” Urban Institute, 2021, Table A.1.

8. The relationships included in the model are estimated through a set of nested multivariate regressions where success at each stage is dependent on earlier success in addition to a group of potentially confounding variables. This means we can control for many variables when doing simulations of one variable on later ones to estimate net effects. Because we know whether a child’s parents are married or not at their birth, we can use the model to simulate how this affects later outcomes throughout childhood and into adulthood after controlling for other variables. The control variables vary from one life stage to another, depending on theory and empirical evidence that they improve the explanatory power of the model. At the time of a child’s birth, we are able to measure parental marital status, mother’s education and her age, and the child’s birth weight. Although income is not measured at time of birth, we do not believe it should be included. We consider it endogenous, meaning we think it is more a result of parents being married than a determinant. We have also found that once we control for mother’s education, it does not add much, if any, explanatory power to the model. We add some caveats at the end of this brief related to possible biases related to both the structure of the model and the data, but efforts to validate it against external research with a quasi-experimental design suggest it is doing a very reasonable job of predicting outcomes.

9. To be “on track” for the pre-K combined math and reading test score and Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) test score submetrics, the child must earn greater than one standard deviation below the mean score on the given test.

10. Isabel Sawhill, Generation Unbound: Drifting Into Sex and Parenthood Without Marriage (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2014); Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill, "The Decline of the American Family,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 667 (September 2016): 8-34; David Ribar, "Why Marriage Matters for Child Wellbeing," The Future of Children 25, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 11-27; Melissa S. Kearney, The Two Parent Privilege (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023); Bradford Wilcox, Get Married: Why the Traditional Family Still Matters (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2024).

11. Ron Haskins, "The Family Is Here to Stay--or Not," Future of Children 25, no. 2 (2015): 129-153.

12. Adam Thomas and Isabel Sawhill, “For Richer or for Poorer: Marriage as an Antipoverty Strategy.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 21, no. 4 (2002): 587–99.

13. Raj Chetty et al., “Where is the land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129, no. 4 (2014): 1553–1623.

14. Isabel Sawhill, "Beyond Marriage," New York Times, September 13, 2014.

15. David Brooks, "The Nuclear Family was a Mistake," The Atlantic, March 2020.

16. Scott Stanley and Galena Rhoades, “What's the Plan? Cohabitation, Engagement, and Divorce," Institute for Family Studies, February 2024.

17. Mia Zolna and Laura Lindberg, "Unintended Pregnancy: Incidence and Outcomes Among Young Adult Unmarried Women in the United States, 2001 and 2008," Alan Guttmacher Institute, 2012.

18. Lawrence Finer and Mia Zolna,"Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011," New England Journal of Medicine 374, no. 9 (2016): 843-852.