Highlights

- The average happiness among 18- to 55-year-old women living with a minor child is higher in countries where more of them work part-time. Post This

- Part-time work is a more realistic option in countries where a larger share of mothers engage in it. And where a larger share work part-time, mothers on the whole are happier. Post This

I failed to get tenure at the University of Maryland in 2007, and so I spent the following dozen years freelancing: adjunct teaching, doing various research consultancies, and blogging. I also gave birth to three daughters during that time, and I felt pretty fortunate to have engaging part-time work that paid well. Despite feeling fortunate, the uncertainty got old quickly. I was constantly searching for the next research contract and for a stable job.

Would moms, like me, be happier if part-time work and stable work could come in the same package?

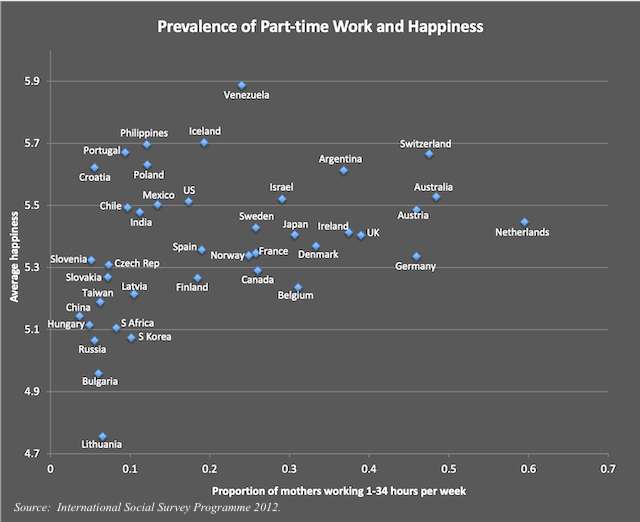

That combination is rare in the United States, and especially rare for professional jobs. And so I looked at whether countries with more ubiquitous part-time employment had happier moms using data from the most recent Family and Changing Gender Roles module of the International Social Survey Programme.

This is what I found.

Note: Respondents were asked to rate how happy they were “on the whole” with seven response options

from completely unhappy to completely happy. Work hours were also self-reported.

The average happiness among 18- to 55-year-old women living with a minor child is higher in countries where more of them work part-time (defined as 1 to 34 hours a week). Specifically, happiness on a scale from 1-7 averages 0.55 higher if the proportion working part-time is 0.10 higher.

Even though this relationship is what social scientists call statistically significant, it is obvious from the spread in the data points that the share of mothers working part-time doesn’t tell us everything we want to know about what makes a happy group of mothers. In other words, the share of mothers working part-time explains some of the variation in happiness, but it also leaves much unexplained. The range in country happiness averages is particularly large toward the left of the graph where few mothers work part-time; where part-time work is more common, the scatter tightens a bit.

In contrast, neither the proportion of non-working mothers nor the proportion of full-time working mothers tells us anything about happiness. In fact, neither the proportion of stay-at-home moms nor the proportion of full-time working moms predicts country happiness, but where part-time work is more common, moms are generally happier (for these findings, see the Table in the Appendix).

Does this mean that moms who work part-time are the happier? No. Concluding that from this country-level data I’ve presented would be what is called an ecological fallacy—inferring information about individuals from what is known about the groups they belong to.

Therefore, I also tested whether, within countries, moms who work part-time are happier than their stay-at-home or full-time working counterparts.1 If they were, it would be easier to understand why countries that had more of them averaged higher on the happiness scale (the effect would be driven by population composition). But individual work status was not a significant determinant of individual happiness. The patterns in the data mean that we should interpret the country-level relationship as a contextual effect: contexts where part-time work is more common are ones where mothers are happier, regardless of their own work situations.

If this doesn’t quite make sense yet, imagine a context where there wasn’t a trade-off between part-time work and job stability. There, moms would be freer to choose whatever work situation made them happy. I suspect that the proportion of mothers working part-time serves as a proxy for the quality of part-time jobs: where they are lousy, few mothers will opt-in, and where they provide attractive alternatives to either no work or full-time work, more mothers will opt-in. I haven’t proven this. But it is reasonable to assume that part-time work is a more realistic option in countries where a larger share of mothers engage in it. And where a larger share work part-time, mothers on the whole are happier.

Laurie DeRose is a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the Catholic University of America, and Director of Research for the World Family Map Project.

1. I used a multi-level model to predict individual happiness from individual work status and controlling for country fixed effects.

Appendix

|

Maternal Work and Women’s Happiness at the Country Level |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note: Data are based on author’s calculations from the Family and Changing Gender Roles module of the 2012 International Social Survey Programme |