Highlights

- In most human societies, poverty does not predict higher fertility, and well-to-do families often have the highest fertility. Post This

- The relationship between income levels and fertility is not some inherent, objective fact, but rather a product of culture. Post This

- The effect of income on fertility is not even remotely consistent across cultures. Post This

Editor's Note: This brief is part 1 of a three-part series on income and fertility.

There’s a common stereotype that poor people have more babies than rich people. This belief is deeply embedded in the American political consciousness, with stereotypes like “welfare queens” often dominating discussions of pronatal policies aimed at boosting birth rates. Likewise, because most people think fertility rates are highest for poorer people, they assume that alleviating costs facing families will not matter that much: if poor women can do it, why not the rich?

This perception, however, is false. In most human societies, poverty does not predict higher fertility, and well-to-do families often have the highest fertility. When families in America have more money, they tend to have more children. The stereotype of fertility being skewed towards low-income women is a product of basically two data analysis errors: 1) failure to control for important underlying cultural stratification, and 2) failure to adequately deal with the relationship between age, income, and fertility. In this post, I’ll tackle the first issue: cultural stratification. In a second post, I’ll deal with the problem of age and family timing.

Culture Matters for Income

People like to spend their money on different things. In some societies, when people get more resources, they spend it on cattle. In others, iPods. In others, religious offerings. And in many other cultures, supporting more children. Anthropological evidence suggests that across almost all pre-industrial human societies, higher-status and higher-income families had more children. But is this true in industrialized societies? Historic demographers debate the question, but there’s a fundamental problem of cultural confounding.

Around the world, income levels have risen at different times and speeds for different groups of people. In particular, economic growth came first for better-educated, upper-class Europeans, and later for other groups, such as Asians or Africans. Groups that got rich earlier also had different cultural norms before getting rich, and then adopted even more unique cultural norms after industrialization. They also had earlier historic declines in fertility in the last several decades. So, we should ask: is it income that drove falling fertility in these groups, or culture? Recent economic historical studies resolve this question tidily: it was culture. Historic fertility declines were overwhelmingly caused by novel cultural norms, and occurred almost irrespective of income and industrialization. In France, fertility fell 100 years before industrialization, while in England, the first country to industrialize, fertility did not decline for a century after industrialization. Today, fertility in Africa is lower than it was for European or Asian countries when they had similar income levels, because modern Africa, though poor, is nonetheless highly exposed to globalized cultural norms. And in fact, at the individual level, when African women get richer, they actually tend to have more children.

But even though fertility transition was largely caused by novel cultural norms, these norms are highly correlated with income. The key takeaway here is straightforward: to figure out what effect income has on fertility, we need to look at the relationship between income and fertility after controlling for cultural norms.

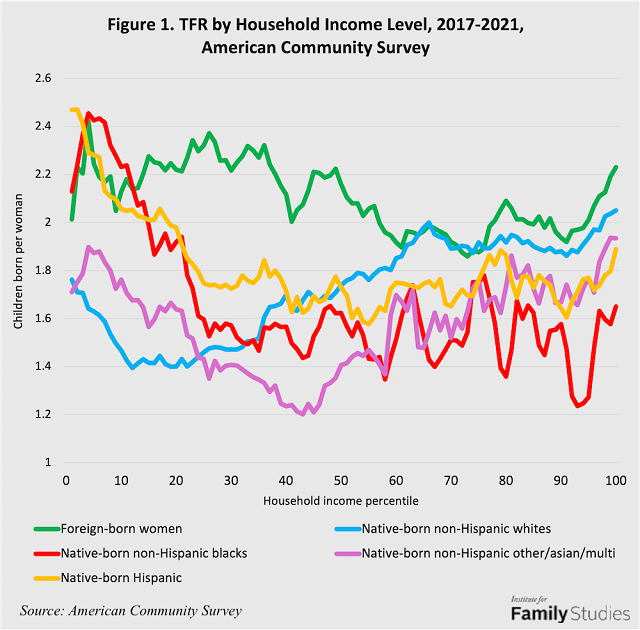

We don’t always have good variables for “culture.” But it seems likely that there are some cultural differences of various kinds across U.S. racial, ethnic, and origin groups. The figure below shows the total fertility rate for women of a given household income level in 2017-2021, by a few different racial, ethnic, or immigrant groupings.

The figure is pretty much just a chaos of crisscrossing lines. That turns out to be important: there is no cross-culturally stable impact of income on fertility.

For native-born non-Hispanic whites, fertility falls from the bottom percentile to the 10th, but then rises throughout middle-income ranges and again above the 90th percentile: high-earning families in this group have above-replacement fertility and have the highest fertility of any income level within their cultural group. Likewise, for the other, Asian, and multiracial category (mostly Asians), fertility falls from poverty levels until middle income, then rises from middle income to high income.

Patterns for native-born non-Hispanic black women and for native-born Hispanic women show a markedly different pattern. For these women, fertility rates are very high at low incomes, then decline until middle income. But unlike the Other/Asian category, for black and Hispanic women, there is no “U-shape.” Wealthy black and Hispanic women have rather low birth rates.

And finally, foreign-born women exhibit little connection between income and fertility, and have almost uniformly the highest birth rates at every income level.

What this graph tells us is that the relationship between income levels and fertility is not some inherent, objective fact, but rather a cultural product. Foreign-born women don’t seem to condition fertility on income. Native-born whites and Asians do; they have more babies as their income increases. Native-born blacks and Hispanics show the opposite pattern: they have fewer babies with higher income.

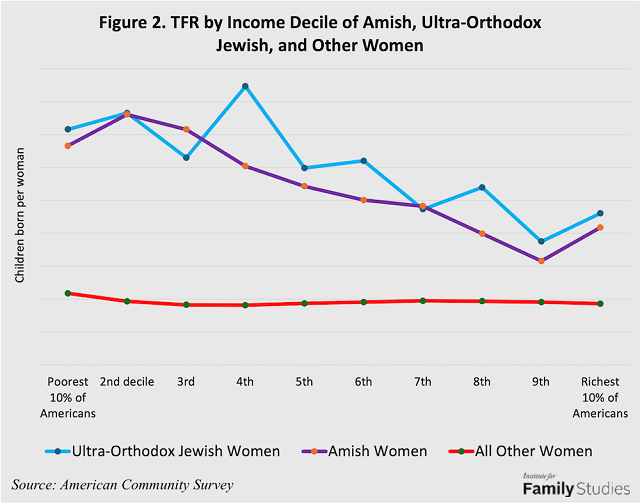

Another way to look at the role of income and culture is to look at how fertility varies by income within extremely culturally different groups, in particular, the Amish and Ultra-Orthodox Jews. Both groups can be identified in the American Community Survey by the fact that they generally speak specific non-English languages at home (Pennsylvania Dutch and Yiddish, respectively). How does their fertility vary across the same income levels? Because the survey samples of these groups are smaller, I cluster respondents by their income decile, basically what tenth of American household income distributions they land in.

Amish and Ultra-Orthodox Jewish women in richer households do have fewer children: their fertility rates fall from about 6 to 8 kids in the poorer income brackets to 3 to 5 in the richest ones. But it’s important to keep perspective here: Amish and Ultra-Orthodox Jewish women in households richer than 90% of Americans are still having approximately double as many children as other Americans in the same income bands, and their surviving family sizes are similar to the prevailing social norms in European societies before 1850. Income matters among these groups, sure, but the massive fertility differences observed for Amish and Ultra-Orthodox Jewish women are overwhelmingly driven by cultural differences, not by differences in economic resources. Thus, while it’s true that Amish and Ultra-Orthodox Jewish women tend to face different economic circumstances (the Amish have slightly above-average incomes in general, but eschew many modern technologies, while Ultra-Orthodox Jewish households are about 28% poorer than other U.S. households, but have adopted more modern technologies), their exceptional fertility behavior exists independently of these circumstances.

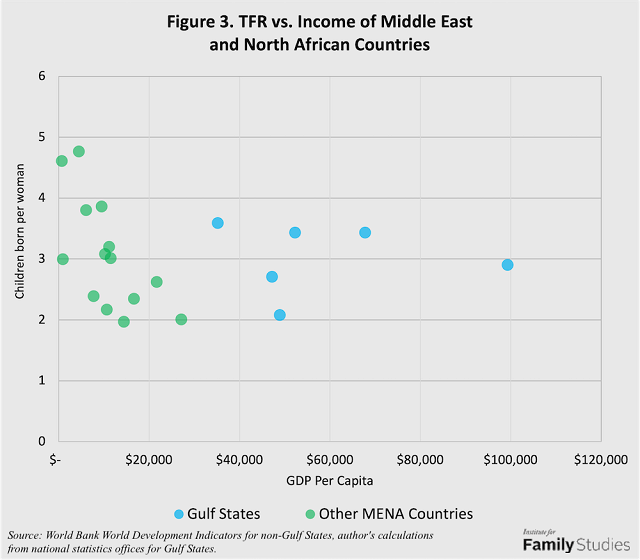

Finally, another way to think about the effect of income on fertility is to look at countries that are very different from the Western world in terms of culture, but nonetheless have extremely high incomes: the oil-rich Gulf states. Citizens of these countries (specifically: Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates) have average incomes in the hundreds of thousands, far more than people in any other country on earth, and they have been getting richer over the last few decades. If high incomes predict low fertility, then their birth rates should be very low. Here’s the reality:

Among the Islamic, Middle Eastern countries without vast oil wealth per person (Egypt, Syria, Turkey, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Sudan, Yemen, Lebanon, Jordan, the West Bank, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Libya), there is a clear negative correlation between fertility and income, as income rises towards $20,000 per person or so. That seems to suggest income might reduce fertility.

But the richer countries in that area, like Azerbaijan, Iran, Tunisia, or Morocco, are not only differentiated by income. They have higher income because of greater historic integration into industrialized markets or other unique historic factors, which also means they have greater cultural exposure to the ideas and norms present in many foreign markets. The Gulf States, however, are exceptional: they became wealthy in recent decades, they remain virtually 100% Islamic, their local varieties of Islam are fairly conservative, they are basically 100% ethnically Arab, and they had little or no integration with the industrialized world before oil was discovered. In these countries, where the discovery of oil unexpectedly and randomly rocketed incomes upwards, fertility rates remain high, similar to the fertility rates observed in countries with just $5,000 to $15,000 in GDP per capita.

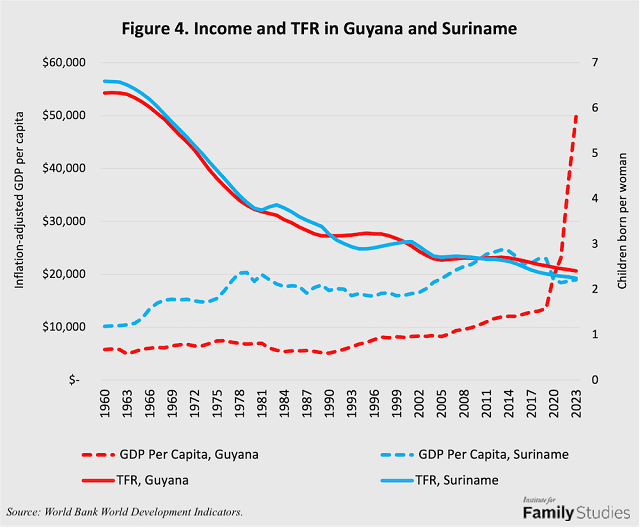

Does this finding that huge income gains don’t cause big fertility declines generalize elsewhere? Why yes, as a matter of fact, it does. Over the last decade, a huge new discovery of oil in Guyana (a small country on the northern coast of South America) has launched Guyanese incomes onto a dramatic trajectory upwards versus their near neighbors in Suriname. And yet, if anything, their fertility has declined less than in Suriname.

On the whole, a clear conclusion emerges: because different cultural groups often have unique income levels, efforts to correlate income and fertility are often deeply misleading. Global fertility decline was kicked off almost entirely by normative and cultural processes, not strictly economic ones. The effect of income on fertility is not even remotely consistent across cultures or even across times. When whole societies become richer, they do not necessarily have fewer children. Once we control for the basic problem of cultural stratification, the supposed link between low income and high fertility, or high fertility and low income, largely disappears.

Lyman Stone is Senior fellow and Director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies.