Highlights

- Focusing on the role that stable families play in mediating the virus points to an even stronger negative association with the virus. This association with marriage is nearly 40% larger than the broader measure of social capital. Post This

- There is a strong association between the strength of marriage in counties across the United States and their ability to slow the spread of the virus. Post This

- Our paper provides quantitative evidence that higher levels of social capital across counties are negatively correlated with infections and the average weekly growth in infections. Post This

The COVID-19 pandemic caught everyone by surprise. While all of us are going through a similar storm, not everyone is in the same boat: some areas are weathering the storm of the pandemic (and the resulting economic and emotional damage associated with the national quarantine) better than others.

My recent research, joint with Cary Wu, explores whether differences in social capital across counties can help explain the differences in the severity of the pandemic. We use data on over 2,700 counties, linking their number of infections and weekly growth in infections between March and April with their social capital, as defined by the Joint Economic Committee (JEC) measure of social capital. Their index of social capital is created as a function of several indicators on family unity, family interaction, social support, community health, institutional health, collective efficacy, and philanthropic health. In brief, social capital measures the degree of trust and solidarity within a community–including the strength of families.

Whether social capital reduces or increases the transmission of the virus is not totally clear on paper. On one hand, greater social capital could lead to more in-person interactions, which would lead to a higher probability of transmitting the virus. For example, collective gatherings in Bergamo helped fuel the spread of the coronavirus in Italy, many scholars conclude. On the other hand, greater social capital could lead to better hygiene, more effective responses to reduce contagion, and greater adherence to social distancing. These two competing theories make for an interesting empirical question that we can take straight to the data.

Our paper provides quantitative evidence that higher levels of social capital across counties are negatively correlated with infections and the average weekly growth in infections. Specifically, moving a county from the 25th to the 75th percentile of the distribution of social capital would lead to a 20% decline in the number of coronavirus infections, as well as a 0.28 percentage point decline in the growth rate of the virus (or nearly 20% of the median growth rate), even after controlling for demographics (e.g., population density).

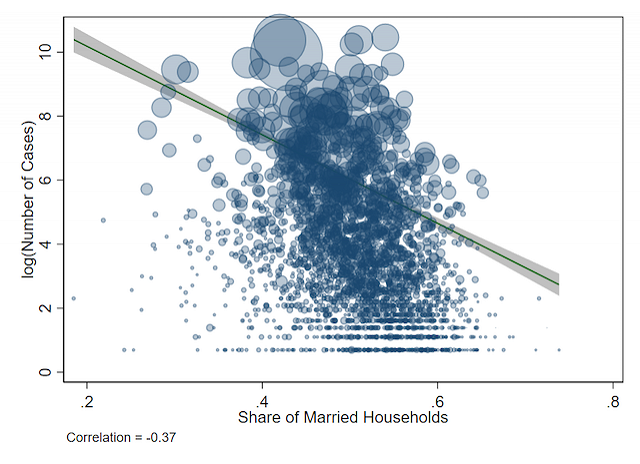

And yet, knowing that social capital matters for mediating the effects of the pandemic is only the first step. We also need to understand if specific policies and features matter in determining the spread of the virus. One important determinant of social capital is family structure, which can be proxied for using the share married in a county. In fact, focusing on the role that stable families play in mediating the virus points to an even stronger negative association with the virus, displayed in the figure below. This association with marriage is nearly 40% larger than the broader measure of social capital.

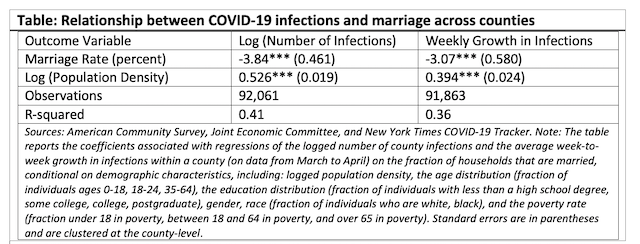

Moreover, the strong negative relationship between the share of married households and infections comes through even after controlling for other demographic characteristics. For example, the table below shows that a 1 percentage-point increase in the share of married households is associated with nearly a 4% decline in infections and a 3 percentage-point decline in the growth rate of infections. Given the wide variance in marriage rates across counties, ranging from 31% in the 1st percentile to 64% in the 99th percentile, these estimates are large, pointing towards the importance of families in weathering the storm. While these estimates are not necessarily causal—since there are other differences between areas with higher versus lower shares of married households—they nonetheless point to the resounding role of marriage as a factor in weathering the storm.

Why would the share of married households be related to the spread of virus? A few theories come to mind: Married households tend to live in single-family homes with more room than an average small apartment, which may reduce their exposure to the virus. Married households also enjoy more income, which may make it easier for them to adhere to social-distancing guidelines or obtain better healthcare options. And married households may also have an easier time maintaining normal levels of mental health.

Whatever the reason, this analysis shows there is a strong association between the strength of marriage in counties across the United States and their ability to slow the spread of the virus. In other words, strong and stable families seem to be more resistant to the pandemic now enveloping our nation.

Christos A. Makridis (Ph.D., Stanford University) serves as an Assistant Research Professor at Arizona State University, a Digital Fellow at the MIT Sloan Initiative on the Digital Economy, a Non-resident fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government Cyber Security Initiative, a Non-resident fellow at the Baylor University Institute for Studies of Religion, and a Senior Adviser to Gallup.