Highlights

On June 20, IFS senior fellow W. Bradford Wilcox testified before the “Committee on Building an Agenda to Reduce the Number of Children in Poverty by Half in 10 Years,” an ad-hoc committee of experts convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to study child poverty in the United States. Below is an edited version of his testimony.

Many factors influence the persistence of comparatively high levels of child poverty in the United States—from relatively low spending on government transfers1 to declines in real wages for men without college degrees.2 But we cannot lose sight of the role that changes in family structure, especially among Americans without college degrees,3 have also played—first, in fueling increases in child poverty and, second, in keeping rates of child poverty higher than they should be.

Research by Robert Lerman of the Urban Institute4 and Isabel Sawhill of the Brookings Institution,5 among others, suggests the growth of child poverty from the 1970s to the 1990s was driven, in part, by the rise of single-parent families and family instability over this time period. For instance, in 1970, 12% of children lived with a single parent; by 1990, 25% of children lived with a single parent. Their work indicates that more than half of the increase in child poverty over this period can be attributed to the decline of stable marriage as an anchor to family life in America. Since then, the retreat from marriage has slowed, which means that family structure has been less salient in the ebb and flow of child poverty. Nevertheless, this research suggests that child poverty would be markedly lower in the United States if more American parents were stably married.

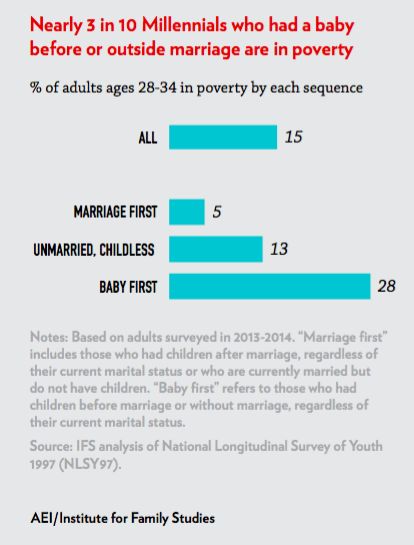

In fact, the continuing relevance of marriage to economic well-being can be seen in two recent studies, both of which suggest that marriage per se is strongly related to poverty. My own recent research with the Institute for Family Study’s Wendy Wang indicates that Millennials who have formed a family by marrying first are significantly less likely to be poor than Millennials who have formed a family by having a child before or outside of marriage. After controlling for education, race, ethnicity, family-of-origin income, and a measure of intelligence/knowledge (AFQT scores), we find that Millennials who married before having any children are about 60% less likely to be poor than their peers who had a child out of wedlock. In fact, as shown in the figure below, 95% of Millennials who married first are not poor by the time they are in their late twenties or early thirties. So, even for the latest generation of young adults, it looks like marriage continues to matter.

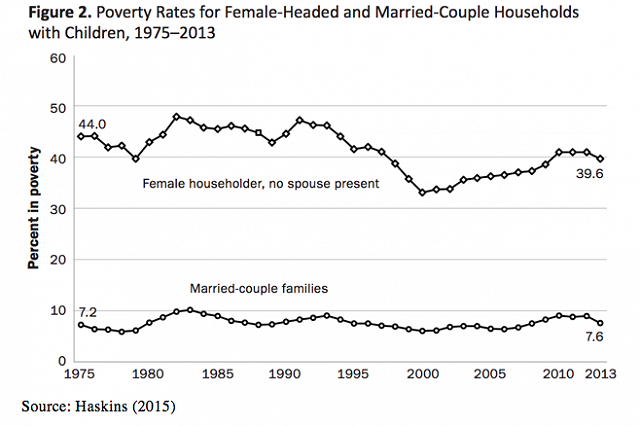

Given the trends for adults noted above, it is no surprise that children from single-parent families are more likely to be poor than children from married-parent families. For instance, as the figure below indicates, since the 1970s, children in single-mother-headed families (who make up the clear majority of single-parent families) are over four times more likely to be poor, compared to children in married-parent families.6 And because more than one-quarter of American children are in single-parent families, this elevates the child poverty rate above what it would otherwise be if more children were living in married-parent families. Sawhill’s research suggests that if the share of children in female-headed families had remained steady at the 1970 level of 12.0%, then the 2013 child poverty rate would be at 16.4%, rather than a rate of 21.3%.7 In other words, the current child poverty rate would be cut by almost one-quarter if the nation enjoyed 1970-levels of married parenthood.

In addressing marriage, family structure, and child poverty now, one additional point needs to be made. Today, a rising share of children are being raised by cohabiting parents. In 2014, 7% of children were living in homes headed by cohabiting parents.8 Might these children benefit financially as much as children from married-parent families by living with two adults?

The answer is no. Not only are cohabiting parents less likely to pool their income and put aside money for family savings, they are also much more likely to split up than are married parents.9 One recent study finds, for instance, that children born to cohabiting parents are almost twice as likely to see their parents break up, compared to children born to married parents, even after controlling for a number of socioeconomic factors.10 This means that children in cohabiting families are more likely to end up in single-parent families or complex families without both their biological parents, which increases their risk of being in poverty.11 All this suggests that cohabitation does not protect children from poverty as much as marriage does.

Why Marriage Matters for Economic Well-Being

Why does marriage matter for the economic well-being of children? First, children raised by their married parents are much more likely to enjoy access to the economic support of their father over the course of their childhood, compared to children raised by single or cohabiting parents.12 Second, married parents are more likely to enjoy economies of scale, compared to single parents, and to pool their income, compared to other types of families.13 Third, stably married parents who do not have children with other partners do not incur child support obligations or legal expenses related to family dissolution that reduce their household income.

Overall, the economic value of marriage for children should not be underestimated. One recent study suggests that having stably married parents is worth about an extra $40,000 in annual family income to children while growing up, compared to children being raised by a single parent.14

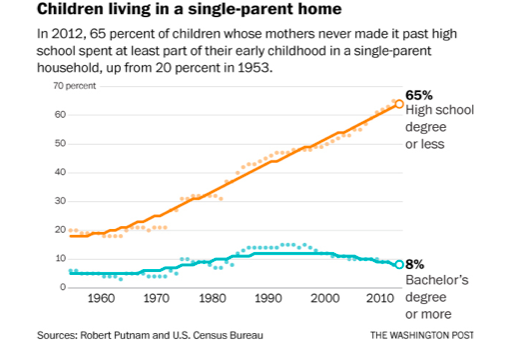

Unfortunately, despite the economic value of marriage for children—not to mention its social, educational, and psychological value15 —marriage has been in retreat since the 1970s, especially among poor and working-class families. In fact, there is a growing marriage divide, such that children from college-educated families continue to enjoy high levels of family stability, whereas children from less-educated families face higher levels of family instability and single parenthood.16 For instance, as the figure below indicates, the share of children with less-educated mothers living in single-parent homes has grown steadily since the 1960s, whereas it has actually fallen for children of college-educated mothers since the 1990s.17 This leaves many children in less-educated homes doubly disadvantaged—they have markedly less income, along with less time and attention from their parents than children in more affluent and college-educated homes.18

What’s Driving the Marriage Divide?

The growing marriage divide is driven in large part by four developments. First, men without college degrees have seen their real wages decline and spells of unemployment increase, both of which make them less attractive as marriage partners.19 Second, changes in public policy and law have made marriage less financially advantageous, especially for lower-income Americans who often face marriage penalties associated with a range of means-tested policies offered by the federal government.20 Third, the erosion of marriage-related norms governing sex, childbearing, and marital permanence, along with the rise of a soulmate model of marriage that increases men and women’s expectations for high-quality marriages, has left lower-income Americans more vulnerable to premarital childbearing, family instability, and divorce—partly because they face fewer opportunity costs for having children out of wedlock, and partly because they face more economic stresses that can undercut the quality of their marriages.21 Finally, civic participation has fallen most among Americans without college degrees; this matters because civic groups—especially religious organizations—have long lent moral and social support to marriage and family life.22

Policy Recommendations

To bridge the marriage divide between less-educated and college-educated Americans, and thereby reduce child poverty, policymakers, business executives, philanthropists, civic leaders, educators, and culture shapers should consider the following four recommendations:

- On the educational front, strengthen vocational education and apprenticeship programs, so as to increase the vocational opportunities of the majority of young adults who will not get a four-year college degree.23

- On the policy front, work to minimize marriage penalties facing lower-income families, perhaps by offering newly married Americans a “honeymoon” period of three years where their eligibility for means-tested programs would not end if they marry—so long as their household income is below a threshold of $55,000.

- On the cultural front, launch local, state, and federal campaigns on behalf of what Haskins and Sawhill have called the “success sequence,”24 where young adults are encouraged to get at least a high school degree, work full-time, and marry before having any children—in that order.

- On the civic front, encourage secular and religious organizations to be more deliberate about targeting Americans without college degrees.

The alternative to taking measures like these is to accept a world where college-educated Americans enjoy stable and strong families, and the economic benefits that flow from such families, and everyone else faces increasingly unstable families and high rates of economic insecurity and poverty.

W. Bradford Wilcox is a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and the director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia.

1. Rainwater, Lee and Timothy M. Smeeding. 2005. Poor Kids in a Rich Country: America’s Children in Comparative Perspective. New York: Russell Sage.

2. Autor, David, and Melanie Wasserman. 2013. Wayward Sons: The Emerging Gender Gap in Education and Labor Markets. Washington, DC: Third Way.

3. Cherlin, Andrew J. 2009. The Marriage-Go-Round: The State of Marriage and the Family in America Today. New York: Vintage. Wilcox, W. Bradford. 2010. State of Our Unions 2010: When Marriage Disappears: The New Middle America. National Marriage Project and Institute for American Values.

4. Lerman, Robert. 1996. Helping Disconnected Youth by Improving Linkages Between High Schools and Careers. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

5. Sawhill, Isabel and Adam Thomas. 2005. “For Love and Money? The Impact of Family Structure on Family Income.” The Future of Children 15(2): 57-74.

6. Haskins, Ron. 2015. "The Family is Here to Stay—or Not." The Future of Children 25(2): 129-153.

7. Sawhill, Isabel. 2014. How Marriage and Divorce Impact Economic Opportunity. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

8. Pew Research Center. 2015. Parenting in America: Outlook, Worries, Aspirations are Strongly Linked to Financial Situation. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

9. Wilcox, W. Bradford. Et al. 2011. Why Marriage Matters: 30 Conclusions from the Social Sciences. New York: Institute for American Values and National Marriage Project.

10. DeRose, Laurie, Mark Lyons-Amos, W. Bradford Wilcox, and Gloria Huarcaya. 2017. The Cohabitation Go Round. New York: Social Trends Institute and Institute for Family Studies.

11. McLanahan, Sara. 2009. "Fragile Families and the Reproduction of Poverty." The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 621(1): 111-131.

12. Sawhill, Isabel and Adam Thomas. 2005. “For Love and Money? The Impact of Family Structure on Family Income.” The Future of Children 15(2): 57-74.

13. Wilcox, W. Bradford. Et al. 2011. Why Marriage Matters: 30 Conclusions from the Social Sciences. New York: Institute for American Values and National Marriage Project.

14. Lerman, Robert, Joseph Price, and W. Bradford Wilcox. 2017. "Family Structure and Economic Success Across the Life Course." Marriage & Family Review: 1-15.

15. McLanahan, Sara, and Isabel Sawhill. 2015. "Marriage and Child Wellbeing Revisited: Introducing the Issue." The Future of Children 25(2): 3-9.

16. Wilcox, W. Bradford. 2010. State of Our Unions 2010: When Marriage Disappears: The New Middle America. National Marriage Project and Institute for American Values.

17. Putnam, Robert D. 2015. Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis. New York: Simon and Schuster.

18. McLanahan, Sara. 2004. “Diverging Destinies: How Children are Faring Under the Second Demographic Transition.” Demography 41: 607-627. Putnam, Robert D. 2015. Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis. New York: Simon and Schuster

19. Autor, David, and Melanie Wasserman. 2013. Wayward Sons: The Emerging Gender Gap in Education and Labor Markets. Washington, DC: Third Way. Wilcox, W. Bradford. 2010. State of Our Unions 2010: When Marriage Disappears: The New Middle America. National Marriage Project and Institute for American Values.

20. Besharov, Douglas and Neil Gilbert. 2015. Marriage Penalties in the Modern Welfare State. Washington, DC: R Street Institute. Wilcox, W. Bradford, Joseph P. Price, and Angela Rachidi. 2016. Marriage, Penalized: Does Social-Welfare Policy Affect Family Formation? Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute and Institute for Family Studies.

21. Cherlin, Andrew J. 2009. The Marriage-Go-Round: The State of Marriage and the Family in America Today. New York: Vintage. Edin, Kathryn, and Maria Kefalas. 2011. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Wilcox, W. Bradford. 2010. State of Our Unions 2010: When Marriage Disappears: The New Middle America. National Marriage Project and Institute for American Values.

22. Wilcox, W. Bradford. 2010. State of Our Unions 2010: When Marriage Disappears: The New Middle America. National Marriage Project and Institute for American Values.

23. Lerman, Robert I. 2014. Proposal 7: Expanding Apprenticeship Opportunities in The United States. Washington, DC: Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution.

24. Haskins, Ron and Isabel Sawhill. 2009. Creating an Opportunity Society. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.