Highlights

- New research is painting a clearer picture of the adults who still marry: more and more, they tend to be the highly religious. Post This

- Marriage is still a relationship steeped in positive benefits, which are now being enjoyed by a dwindling proportion of the adult population. Post This

- Just as marriage rates are slowly declining, as marriage becomes the institution of the religious, the number of religious couples is also decreasing. Post This

Marriage appears to be a dying institution that fewer couples are choosing. Year after year, couples who marry are increasingly becoming a unique group compared to their peers. A recently published study suggests that perhaps, more than ever before, marriage is becoming a relationship status tightly tied to a dwindling religious sub-population in the United States. While some may look at these findings and feel mostly apathetic at the potential death of an institution, there are many important reasons gleaned from recent social science research to be concerned about these trends.

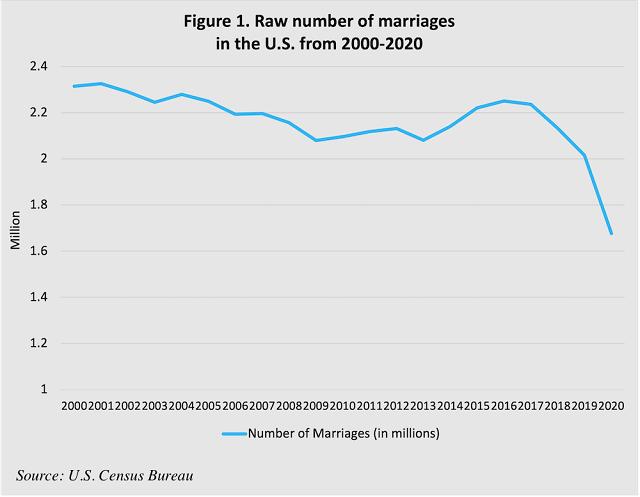

Almost universal data now show that in most parts of the world, marriage rates are decreasing and the proportion of the population who has ever married is shrinking. Perhaps one of the best illustrations of this shifting tide lies in the raw number of marriages documented each year. While the annual marriage rate is a helpful statistic because it adjusts for the size of a population, the raw number of marriages is more illuminating in this case. That is because with most demographic trends, raw numbers tend to increase over time simply by virtue of population increase. The more people, the more marriages, even if the actual marriage rate per capita is decreasing. This is why the marriage rate (usually per 1,000 people) is often a preferred metric when we try to understand trends in behavior. However, when one looks at the raw number of marriages in the U.S., a clear and unique pattern emerges. Despite steady population increases each year, the number of marriages has been decreasing over the last 20 years. While there was a slight uptick in the economic recovery years following the Great Recession, the number of marriages has not only continued to drop more recently but has been dropping at an accelerating rate over the last few years (Figure 1).

While there are many overlapping factors related to this decline, experts have pointed to changes in both the behavior and attitudes of younger generations as a primary reason for these shifts. Young adults today still tend to value and plan for marriage, but the actual proportion of the younger adult population that is married has been dropping steadily over the last two decades. I’ve described this phenomenon as the marriage paradox. Starting roughly around the turn of the millennium, young adults began to retreat from marriage despite their continued insistence that they wanted to get married at some point in their life. Further research has shed light on this, suggesting that many young adults value marriage but prioritize education and other life goals more than long-term committed marriage. While many adults are still marrying, and marriage does not appear to be disappearing from society, the proportion of the adult population choosing marriage is dwindling. New research is painting a clearer picture of the adults who still marry: more and more, they tend to be the highly religious.

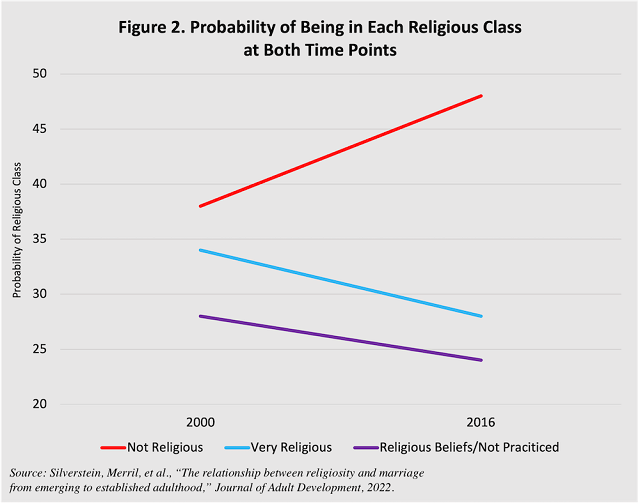

Backing up this theory, Silverstein and colleagues utilized a longitudinal sample of several hundred individuals who were young adults around the year 2000 and are now mostly in their late 30s and early 40s. This cohort represented the beginning of the Millennial generation. The research included data collected during their young adult years around 2000 and then another data collection period almost 20 years later in 2016.

The authors first noted the presence of three types of people in their sample at each time point based on their religious behavior and beliefs. The largest group includes the non-religious. The second group was strongly religious, and the third group held beliefs about the importance of religion and general beliefs in God and the Bible, but did not practice their beliefs in their daily lives or consider themselves religious. The authors found that those in the strongly religious group were significantly more likely to be married at the second wave of data collection 16 years later than either of the other two groups. This was particularly true for the men in the study: 97% of highly religious men were likely to be married by their mid-40’s, compared to only 65% of non-religious men.

These findings are similar to what I have found in my own studies of married Millennials. In my recent examination of young married couples, I noted that many of these couples were quite religious, and when they talked about their courtship process during young adulthood, they approached dating and marriage differently than others in their cohort. For example, religious individuals were much more likely to have dated in young adulthood with marriage in mind and were more likely to prioritize getting married over other life goals. These were traits that were common among most segments of the population a few generations ago, but now appear to be largely concentrated among highly-religious married couples, and are a contributing factor in why they are so much more likely to marry than their peers.

Taken all together, these recent findings confirm what I and others have been noting for several years. Marriage is slowly becoming an institution mostly utilized by the religious, who continue to view marriage as a symbolic representation of life-long commitment to one’s partner. While non-religious couples certainly value commitment and still get married, more and more non-religious couples are opting for long-term cohabitation, while an increasing number of individuals in the U.S. and Europe are electing to remain single.

Marriage, a relationship status that has long been associated with numerous positive benefits, is struggling to remain relevant.

Why does this matter? It matters because marriage is still a relationship steeped in positive benefits, which are now being enjoyed by a dwindling proportion of the adult population. Decades ago, Linda J. Waite and Maggie Gallagher found strong evidence of a positive marriage effect to justify what they described as “the case for marriage”: married individuals were healthier, happier, and generally just better off than their single counterparts. In the many years since, some have questioned if this marriage effect is still relevant for today’s adult population. After all, as social norms and expectations surrounding marriage have eroded, perhaps the benefits of marriage have likewise disappeared.

Yet a large national study I published two years ago found this wasn’t the case at all. Using several recently collected datasets, I showed that married Millennials were still, in fact, reaping the benefits of marriage, regardless of their religious beliefs or behaviors.

Consider these findings from that study: married Millennials . . .

- were more likely to report satisfying and stable relationships compared to Millennials in other types of committed relationships;

- were more likely to have better access to health care, retirement benefits, and insurance compared to unmarried Millennials;

- reported better health and more regular exercise than those who weren’t married;

- were significantly less likely to report depression than single Millennials.

These findings confirm that married couples still reap the benefits of the long-term stable relationship that their union provides. These financial, emotional, and physical benefits have been documented across multiple datasets and still exist for the rising generation.

Yet recent trends and studies suggest that more couples than ever before are content with bypassing these benefits. Religious couples will likely always marry at higher rates than non-religious couples. But current trends suggesting that religious couples may soon be the only types of couples that elect to marry indicate that the benefits of marriage may increasingly be left by the wayside for many. Silverstein and colleagues’ study also found that the proportion of highly-religious adults in their sample was significantly lower 16 years later (see Figure 2). Just as marriage rates are slowly declining, as marriage becomes the institution of the religious, the number of religious couples is also decreasing. Both factors compound the same issue. Marriage, a relationship status that has long been associated with numerous positive benefits, is struggling to remain relevant.

Without a continued effort to educate individuals and couples about the benefits of long-term marriage, we are at risk of one of the best ways to establish a healthy and stable foundation for families disappearing altogether. In a world that offers modern couples and individuals a wide array of relationship choices, marriage remains a key component in creating the stability needed to provide families, couples, and parents with the greatest likelihood of success. If marriage continues to become a novelty of a shrinking religious group, we may continue to see erosion across multiple aspects of family well-being.

Brian J. Willoughby, Ph.D. is a Professor in the School of Family Life and a Fellow of the Wheatley Institution.