Highlights

When marriage breaks down, boys are more likely than girls to act up. From delinquency to incarceration and schooling to employment, a mounting body of research suggests boys are affected more by family breakdown than girls. As Richard Reeves, the co-director of the Brookings Center on Children and Families, recently put it, when it comes to thriving in difficult family environments, girls may be more like dandelions, while boys may be more like orchids.

“In psychology, people used to talk about dandelions and orchids...but the idea is that dandelions pretty much survive whatever you do, and orchids need to be carefully looked after,” said Reeves, “Well, it looks from the evidence as if it's the boys who are the orchids in many cases." That is, girls appear to be more resilient in the face of family instability and stress than boys.

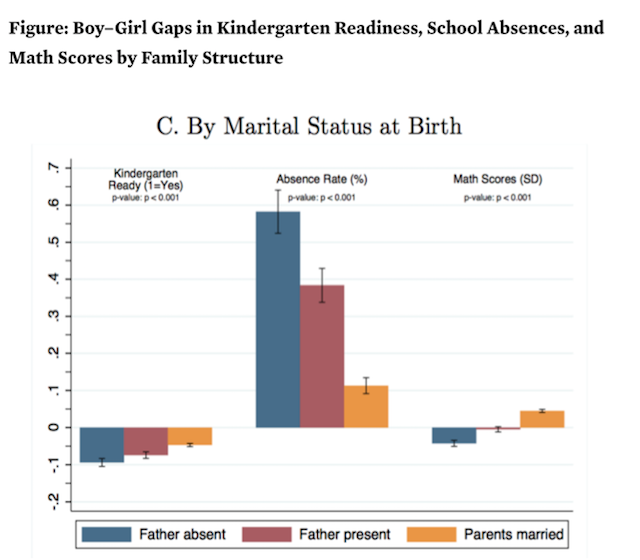

Is Reeves right about boys and girls? Up until now, I have taken the view that boys now seem more vulnerable than girls in the face of family instability. Recent research by economist David Autor and his colleagues indicates that one major reason why boys are falling behind girls in school is that they are affected more by fatherlessness than girls when it comes to their behavior and academic progress. The figure below, taken from Autor’s new research in Florida, indicates that the gender gap in school absences is larger for boys from unmarried, father-absent homes than for boys born to married parents. Likewise, the gender gap in school suspensions and high school graduation in Florida is also smaller for boys from married homes.

Source: David Autor, David Figlio, Krzysztof Karbownik, Jeffery Roth, and Melanie Wasserman, “Family Disadvantage and the Gender Gap in Behavioral and Educational Outcomes,” NBER, Oct. 21, 2015.

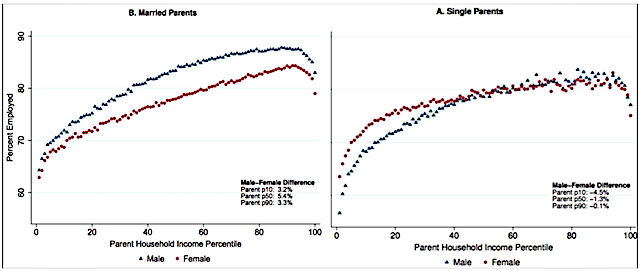

Similarly, economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues have found that young men (at age 30) are less likely to be employed if they come from single-parent families than from married-parent families. Moreover, as the figure below indicates, young men from lower-income families do relatively worse than their female peers if they hail from single-parent families. But young men from married, lower-income families do relatively better than their female peers. In other words, Chetty’s new research suggests that young men’s labor force participation is affected more negatively by single-parenthood than young women’s employment prospects, especially when both are raised in a lower-income family. Overall, the research indicates boys and men are affected more by family instability and single parenthood while growing up than their female peers—at least when it comes to behavioral problems, incarceration, schooling, and employment.

Source: Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Frina Len, Jeremy Majerovitz, & Benjamin Scuderi , "Childhood Environment and Gender Gaps in Adulthood," NBER, Jan. 2016

As Ron Mincy and I noted in USA Today earlier this year, Autor offered two explanations for this pattern: “Boys particularly seem to benefit more from being in a married household or committed household—with the time, attention and income that brings,’” Autor said. The lack of a male role model in impoverished, fatherless households led by single mothers seems to be having a disparate effect. “It’s quite possible that daughters are drawing the lesson that I’m going to be the sole provider and the head of the family,” Autor further noted. “Sons could be drawing the lesson that the men I see around me are not working or committed fathers.”

To date, then, the research suggests that Reeves is right: boys are more likely to be fragile orchids and girls are more likely to be resilient dandelions in the face of family instability.

But it’s also possible that family instability and single parenthood affect girls and young women in ways that are not directly related to antisocial behavior, which is a classic male expression of emotional turmoil. In other words, perhaps both boys and girls are orchids in the face of family instability, but their vulnerability is simply expressed in different ways.

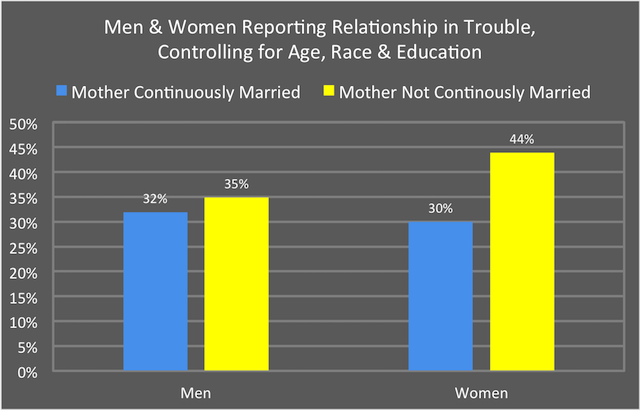

This possibility came to mind after I reviewed data from the 2016 “American Family Survey” conducted by YouGov for Deseret News/BYU. The new survey indicates that on two outcomes—relationship trouble and financial distress—women appear to do worse than men when they have a history of family instability while growing up. For example, adult women are much less likely to report that their current relationship is “in trouble” if they come from a stable married home, and the advantage they enjoy from stability is clearly larger than the advantage that man from a stable home enjoy in this domain (see figure below).

Source: American Family Survey, 2016

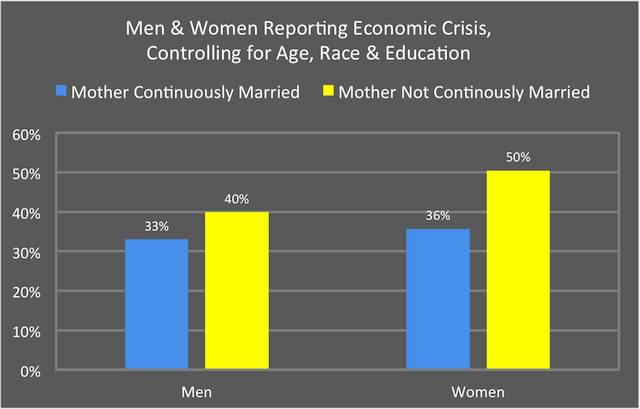

Likewise, today’s women are much less likely to find themselves in a financial crisis if they hail from an intact, married family, as the figure below indicates. If the results of this survey are replicated in other data sets, they suggest that women may be affected by family instability more than men when it comes to their relationship success and freedom from economic distress.

Source: American Family Survey, 2016

This survey suggests women have greater difficulty in forging and maintaining strong relationships as adults when they have been exposed to family instability or dysfunction as children. This, in turn, may lead to more relationship “trouble” and also to a higher incidence of single parenthood as adults. A higher incidence of single parenthood, in turn, may help explain why women with unstable families are more likely to report financial distress. Finally, if the absence of a stable, married home has a bigger impact on girls’ future relationship trajectories than boys, it may also explain why the gap in relationship trouble and financial distress by family stability looks bigger for women than men in this new survey.

Additional research, using different data, is needed to explore whether the relational and economic fallout of childhood family instability in adulthood is now bigger for females than it is for males. But this year’s American Family Survey suggests that Reeves might be wrong about boys being orchids and girls being dandelions when confronted by family instability. It just may be that girls are orchids too, but their vulnerability shows up not so much in their odds of incarceration, school failure, and idleness, but in their odds of being less able to successfully forge strong and stable marriages as adult women.

W. Bradford Wilcox is director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies.