Highlights

- Marriage and mental health are intimately linked for all Americans, regardless of their demographic profile. Post This

- Married people are approximately 16% more likely than unmarried people to describe their mental health as “excellent” or “very good” within every category of formal education. Post This

- Married women were significantly more likely to describe their mental health as “excellent” or “very good” than unmarried men (51.5% to 41.9%). Post This

Despite viral TikToks and widely-circulated testimonials to the contrary, the hard data show that marriage is a strong predictor of happiness. To take just the most recent example, a new study by economist Sam Peltzman found that marriage is the “most important differentiator” between who is “happy” and who is not, with married people 30% more likely to say they were “happy” than unmarried people.

But “happiness” is only one, relatively narrow way that people might think about their well-being. While a person might not be “happy,” they might still feel stable, balanced, and content. Does the “marriage advantage” extend to these subtler perceptions of subjective well-being?

The 2022 Cooperative Election Study survey (CES) helps answer this question. The CES asked its respondents to assess the overall quality of their mental health (“Would you say that in general your mental health is…excellent, very good, good, fair or poor?”) and included an array of items measuring who respondents are and what they believe. It also sampled enough Americans (60,000) to draw meaningful generalizations about every major demographic group in the country.

The CES data show that married people seem to receive a large mental health dividend that pays off quickly and does not diminish over time. As the figure below shows, there was no meaningful difference in the percentage of those married in the last year (55.9%) and those married more than a year ago (57.1%) who reported “excellent” or “very good” mental health. By contrast, only 38.4% of those who were not married described their mental health in this way.

By far the most striking conclusion to emerge from the CES is that marriage seems to confer its mental health benefits indiscriminately; that is, members of nearly every major demographic group in American society is better off from a mental health perspective relative to their unmarried peers. Specifically, being married is significantly correlated with better mental health among men and women, young and old, rich and poor, uneducated and educated, religious and secular, white and non-white, liberal and conservative and parents and those without children.

Consider gender. Recent studies show striking gender differences in mental health, with women reporting higher rates of anxiety, depression, and other mental health struggles. Consistent with these studies, the 2022 CES data shows that women are less likely to say that their mental health is “excellent’ or “very good” than men (42.8% to 51.3%).

Being married, however, was associated with better mental health among members of both sexes. The benefits of marriage are so large, in fact, that married women were significantly more likely to describe their mental health as “excellent” or “very good” than unmarried men (51.5% to 41.9%).

What about age? There’s been a steady stream of concerning studies about the low and declining quality of young people’s mental health. The CES’s data confirms this work’s gloomy assessment. While more than 70% of the Silent Generation and 60% of Boomers report “excellent” or “very good” mental health, only 29.4% of Gen Z do.

But, as the figure above shows, being married is correlated with better mental health regardless of when a person was born. More importantly, marriage’s mental health benefits appear to matter most for the youngest Americans. The mental health gap between the married and unmarried is 5.2% for the Silent Generation, 11.4% for Boomers, 15.0% for Gen X’ers, 16.4% for Millennials and 15.7% for Gen Z’ers.

Generally speaking, money helps mental health. In the 2022 CES, “excellent or “very good” mental health was reported by 36.8% of Americans making less than $40,000 a year but 60.7% of Americans making more than $150,000 a year. This is not the whole story, however. Once again, marriage is associated with elevated mental health at every level of annual income.

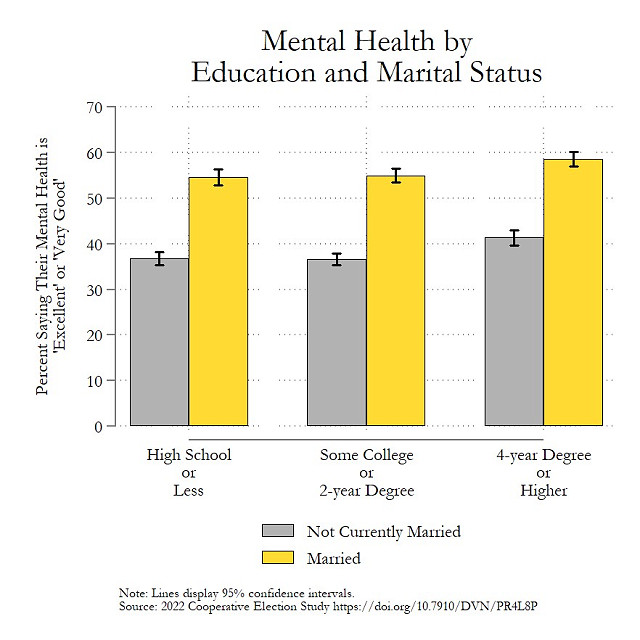

Marriage has a similar effect on well-being across levels of educational attainment. Married people are approximately 16% more likely than unmarried people to describe their mental health as “excellent” or “very good” within every category of formal education.

Church-going is also a key factor. Political scientist Ryan Burge has convincingly shown that “as religious attendance goes up, the likelihood of mental illness goes down.” The figure above confirms this basic relationship but adds something more: married people have considerably better mental health than non-married people independent of how frequently they go to church.

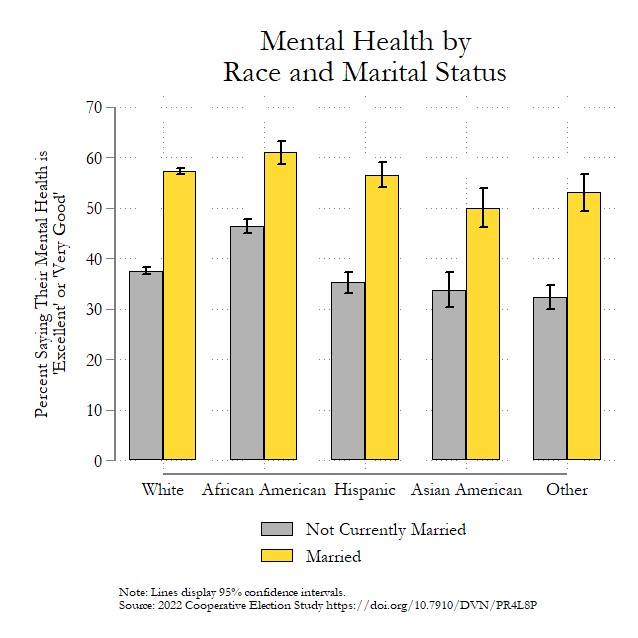

Few institutions in American society exert equal effects across the country’s vast racial divides. Yet in terms of mental health, marriage does. As the above figure illustrates, the mental health gap between married and unmarried is 19.8% among whites, 14.6% among African Americans, 21.3% among Hispanics, 16.3% among Asian Americans, and 20.9% among members of other racial groups.

According to sociologist Musa al-Gharbi, “the well-being gap between liberals and conservatives is one of the most robust patterns in social science research.” The ideological asymmetry in well-being was also present in the CES, where 37.8% of liberals and 59.9% of conservatives said their mental health was “excellent” or “very good.” Despite these baseline differences, the “marriage advantage” apparently applies to people across the political spectrum. In fact, marriage gaps in mental health were larger than 10% within each ideologicaly-defined category. Here, it’s also important to note that conservatives are markedly more likely to be married than liberals (59.3% to 35.1%). If liberals and conservatives were married at equal rates, it would likely cut the overall mental health gap between liberals and conservatives by roughly half.

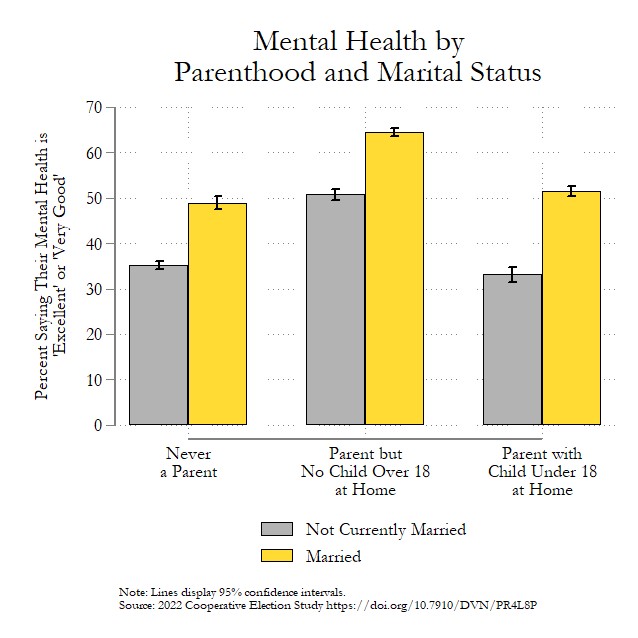

Finally, the same basic story can be told about parenthood. Regardless of how many children a person has, marriage is associated with significantly better mental health.

The Marriage Advantage

The “marriage advantage” for mental health is invariant with respect to gender, age, education, income, church attendance, race, political ideology, and parental status. The size of this “advantage” within groups is typically large and, with a few small exceptions, remains statistically significant even in a multivariate analysis incorporating a full range of controls.1

This analysis, of course, cannot tell us whether marriage-based differences in mental health are caused by marriage itself or simple self-selection. It also cannot tell us which aspects of matrimony are responsible for producing marriage’s mental health benefits. In his new book, Get Married, for example, Brad Wilcox notes that “marriage is the best defense against loneliness.” Unfortunately, we cannot say how much of the mental health boost experienced by married people is a result of this companionship.

It can tell us, however, that marriage and mental health are intimately linked for all Americans, regardless of their demographic profile. It also suggests that an America with more marriage would be an America with more overall well-being.

Kevin Wallsten is a professor in the Department of Political Science at California State University, Long Beach.

1. I ran an OLS regression model predicting mental health based on each of the individual-level attributes mentioned above (as well as employment status and urbanicity) and their interactions with marital status. The significance of the marginal effects associated with interaction terms in a model such as this is far more important and revealing than the significance of the interaction terms alone. Using this approach, all but three of the relationships detailed above (among Asian Americans, among members of “other” racial groups and among members of the Silent Generation) were significant after the addition of statistical controls.