Highlights

The arc of justice should bend to the “least advantaged” among us, contended the late Harvard professor John Rawls in his landmark book A Theory of Justice (1971). Rawls, perhaps the greatest liberal philosopher of the last half-century, argued that societies could be judged just insofar as they promoted “fair equality of opportunity” for their most vulnerable members. In other words, justice is about fairness for the least of us.

Which metropolitan region in America comes closest to embodying the aspirations of one of America’s greatest liberal philosophers? The surprising answer is the Salt Lake City metropolis.

According to a recent study from Harvard and UC-Berkeley, out of the largest 100 metropolitan regions in the country, the Salt Lake City area is best at promoting absolute economic mobility for lower-income children and embodying the Horatio Alger story. Children from the bottom 20% of the national income distribution in the Salt Lake City region were more likely to “reach the top 20% of the national income distribution” as adults than poor children hailing from any other major metropolitan region in America.

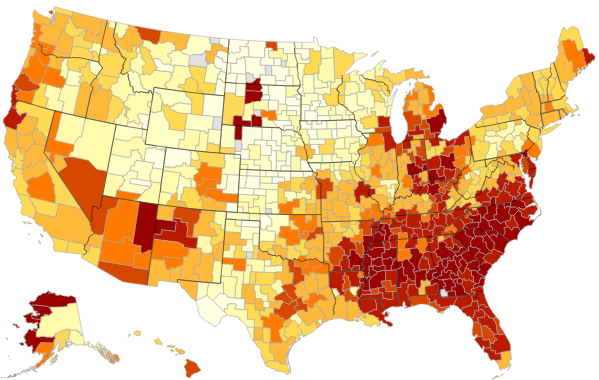

Lighter colors represent areas where children from low-income families are more likely to move up in the income distribution. Source: Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, and Emmanuel Saez. 2013. The Economic Impacts of Tax Expenditures: Evidence From Spatial Variation Across the U.S.

What accounts for the area’s success? The study does not specifically focus on Salt Lake’s comparative advantage for kids, but it does suggest two factors that are key to fostering income mobility for children around the United States: family and civil society. Specifically, the Harvard-Berkeley study that the New York Times called the “most detailed portrait of income mobility in the United States” found that the most powerful (negative) correlate of such mobility was the share of single moms in a region. This means that children were most likely to realize the American dream when they came from regions—like the Salt Lake City area—with comparatively strong families. Utah, for instance, has some of the lowest rates of nonmarital childbearing and highest shares of its adult population married of any state.

Likewise, the study also found that the strength of a region’s civil society was strongly correlated to economic mobility. Communities rich in social capital and religiosity, for instance, were more likely to foster economic mobility for children. And Utah is one of the most religious states in the country, and it scores high on national indices of social trust. Accordingly, the study provides strong prima facie evidence that the Salt Lake City metro success story may be attributed in part to its robust civic life.

To be fair, correlation is not causation. It’s always possible that other factors besides the Salt Lake City metro region’s strong families and strong civic institutions explain its comparative advantage in economic mobility. The study also found that strong schools and high levels of economic integration—with more poor families living in mixed-income communities—were also correlated at the community level with higher levels of income mobility for children. These findings are consistent with the progressive notion that liberal institutions and values play a central role in fostering the American dream for the nation’s poorest children. They also may help explain why more secular, progressive metro regions like Boston and Seattle ranked highly in the study, too.

The success of liberalism may depend in part on thriving non-liberal institutions, including family and civil society.

Still, the Salt Lake City metro success story suggests, as William Galston noted in his classic Liberal Purposes (1991), a certain paradox for our day: namely, the success of liberalism may depend in part on thriving non-liberal institutions, including family and civil society. Galston, a noted Democratic political philosopher who now serves as a fellow at the Brookings Institution, was particularly attentive in this book to the importance of the family in cultivating such liberal virtues as self-mastery, independence, moral responsibility, and law abidingness. He wrote: “From the standpoint of economic well-being and sound psychological development, the evidence indicates that the intact, two-parent family is generally preferable to the available alternatives.”

For Galston, it followed that family life could not be governed by liberal principles such as “individual freedom and choice” but, rather, families with children needed to be attentive to traditional moral categories such as duty and responsibility. In other words, realizing the Rawlsian vision of justice for the least among us, and giving poor kids a shot at the American dream, may depend on the nation’s capacity to revive communitarian virtues and institutions.