Highlights

- Just wanting to find a mate and build a family together appears to make people feel as satisfied with their lives as the married folks who have less of that desire. Post This

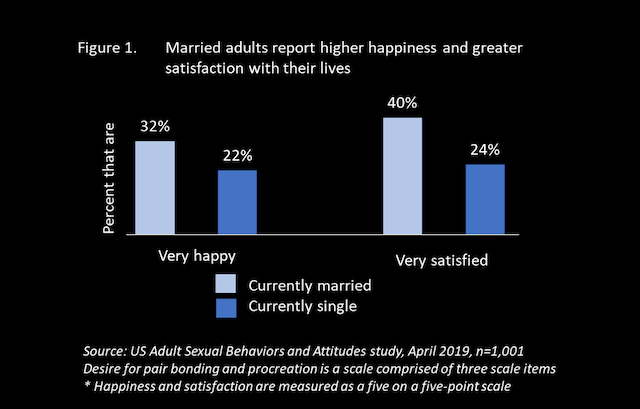

- Per a recent survey, 32% of married adults say they are generally very happy measured as a 5 on a five-point scale, vs. 22% of those not currently married. Post This

Read the latest elite publications and you’d be tempted to conclude that the effect of marriage on people’s well-being is uncertain. A July piece in The Atlantic titled, “What You Lose When You Gain a Spouse,” tried to suggest that married people retreat into socially neglectful cocoons, while the new book Happy Ever After by London School of Economics professor Paul Dolan suggested that a reason married people are happier is that wives in particular are being asked about their happiness in the presence of their spouses and are too afraid to admit how unhappy they are (this is not the case, and the book had to be corrected because this finding was an egregious, methodological error).

While neither of these publications has the facts correct, their currency suggests that many people are willing to believe that marriage is or should be waning. This, in spite of the considerable and consistent statistical evidence showing that marrieds are better off than singles—their happiness is higher, their health is typically better, and their financial stability is greater. The honest question isn’t whether married people are happier but where that happiness comes from.

Do married people experience a happiness bump or are happy people more likely to seek and find marriage?

I approached this question as part of an April 2019 study of the sexual behaviors and attitudes of 500 men and 501 women in the U.S. (for the details of the study, please see the footnote).1 I established a baseline by simply comparing the happiness and life satisfaction of married adults to single adults and found results that are similar to prior studies: 32% of married adults say they are generally very happy measured as a five on a five-point scale, compared with 22% of those not currently married. With life satisfaction, the numbers are even more pronounced—40% of married adults are very satisfied with their lives compared with 24% of unmarried adults in the survey.

But that doesn’t tell us whether or not marriage itself influenced their happiness and life satisfaction or if it works the other way around. If happiness precedes marriage, what is that happiness made of and does marriage do something to amplify it?

I formulated this question using an evolutionary approach to human mating. If humans evolved to seek mating opportunities, that desire to mate should be reflected in our psychology. If our psychology primes us to be made happier by finding a long-term mate, for example, then we should also feel happy just contemplating mating and marriage even before we achieve it.

To test if this is true, a scale measure of the overall desire to pair bond and procreate was created. Survey respondents were asked how much they want to have an emotionally intimate connection with another person in their ideal relationship, whether they think having children is an important part of a meaningful life, and whether they want to give and receive sexually exclusivity in their intimate relationships.

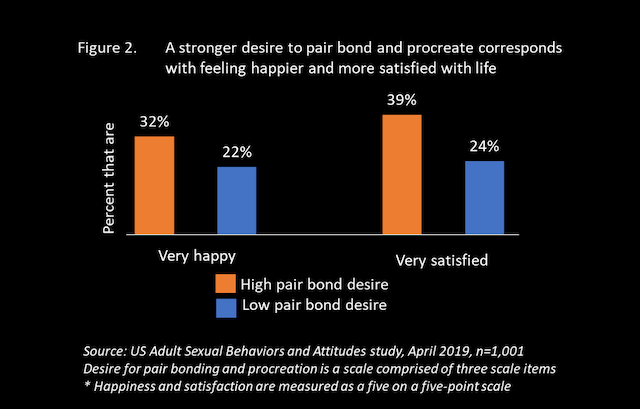

These three questions were then combined into a single measure. I found that scoring higher on this combined scale of desire to pair bond and procreate makes it more likely that a person will report being happy. And, as I’ll show, being married multiplies the effect.

To illustrate this, I compare the 42% of people, single or married, who scored highest on the pair bond and procreation scale with the 58% who score lowest on the scale. As Figure 2 shows: 32% of these pair-bonders are very happy and 39% are very satisfied with their lives. For people with a lesser desire to pair up, the numbers go down: 22% are very happy and 24% are very satisfied.

But is this just because the people eager to pair up have already paired up and marriage has made enough of them happier to tip the scales?

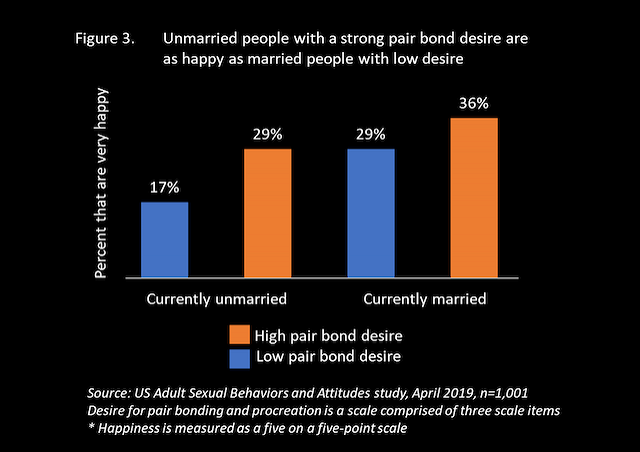

By separating out married and unmarried respondents, we can examine their well-being separately. As shown in Figure 3, it turns out that among those with a high desire for a mate but who don’t have one yet, they are as likely to be very happy as the people with a low pair bond desire but who are currently married.

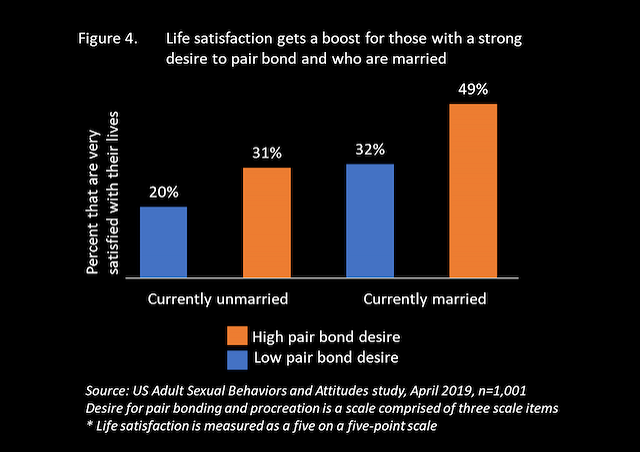

But the real evidence that there’s something powerful going on here shows up when we look at life satisfaction. We could argue that people who have the stronger pair bond desire marriage but just haven’t married yet should actually have less life satisfaction; after all, the thing they so strongly want currently eludes them.

Apparently not, as Figure 4 shows. Just wanting to find a mate and build a family together appears to make people feel as satisfied with their lives as the married folks who have less of that desire—they come in at the statistically indistinguishable 31% and 32%, respectively. Either thing—marriage or the desire to pair bond—is associated with being more satisfied with your life than people who have neither. But the big bump comes when you have both. A full 49% of married people who have the stronger-than-average desire to pair bond and procreate report that they are very satisfied with their lives.

Consider what that says: If you merely have the desire to pair bond and procreate, you are already happier than average and as satisfied with your life on average. But if you act on that desire, your happiness jumps and your life satisfaction practically leaps off the chart.

This suggests that the popular press has it all wrong. What is still unclear is why some people have that desire more than others in the first place. Possible explanations for this desire are likely to range widely. Individual characteristics can apply, including a person’s own physical health or career prospects. Of course, the experience of a stable marriage should apply, including whether one’s parents were married and whether those parents were perceived to love each other. Cultural factors certainly apply, including the propensity to promote marriage among those of one’s ethnic group as well as membership and participation in religions that emphasize marriage. I will explore these and other possible explanations for the desire to pair bond in future analysis of this data.

For now, those who are on the edge of a decision about whether to seek a lifelong partner, to commit to investing in having and raising children, and to be faithful to that commitment can ignore the hype around the “imminent demise” of marriage. This survey’s findings suggest that you will be happier if you take the plunge than if you don’t. The stronger the desire, the bigger the bump. That’s happy news, indeed.

James L. McQuivey (Ph.D., Syracuse University) has taught at Boston University and Syracuse University. He is a consumer behaviorist and analyst who is regularly sought for commentary by publications like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. His research into family studies focuses on human mating strategies and the role of parents in determining positive life outcomes. He is the author of the book Why We Need Dad. Follow him on Twitter @jmcquivey.

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.

1. In April, 2019, the a survey of US Adult Sexual Behaviors and Attitudes was fielded to a US representative sample of adults ranging in age from 18 to 74. The outgoing sample was balanced by sex, age cohort, and US Census region. Sample sourced from and data collection provided by Dynata, a global leader in first-party data and data services. The respondents were weighted back to the outgoing sample parameters for sex, age, and region. Data were validated for internal consistency and compared for population representation to US Census data and GSS data for income, rates of marriage, and childbearing. The project was conceived, designed, executed, and paid for entirely by Dr. James McQuivey.