Highlights

- Almost half of U.S. adults say single women raising children on their own “is generally a bad thing for society,” an increase of 7 percentage points since 2018. Post This

- "People have seen scores of friends and family members move in together with more of those relationships ending than continuing," noted Dr. Stanley, "so it is possible that the bloom is off the rose a little bit." Post This

- More American adults say that “couples living together without being married” is generally bad for society compared to three years ago, per a recent Pew survey. Post This

Opinions on two family patterns that affect the well-being of children might be changing in the United States. Even though more adults are cohabiting today than in the past and the U.S. still leads the world in the rate of kids raised in single-mother homes, recent research indicates that Americans' views on single motherhood and living together outside of marriage have grown more negative, even as the practice of cohabiting in the U.S. appears to be stalling.

Could these changes have anything to do with the pandemic of the past two-plus years? Or is it simply that more Americans have experienced or witnessed both family patterns and now view them in a more realistic light? These are some of the questions I posed to University of Denver social scientist and IFS senior fellow, Scott Stanley, a noted expert on cohabitation.

More Americans See Women Raising Children Alone As Negative for Society

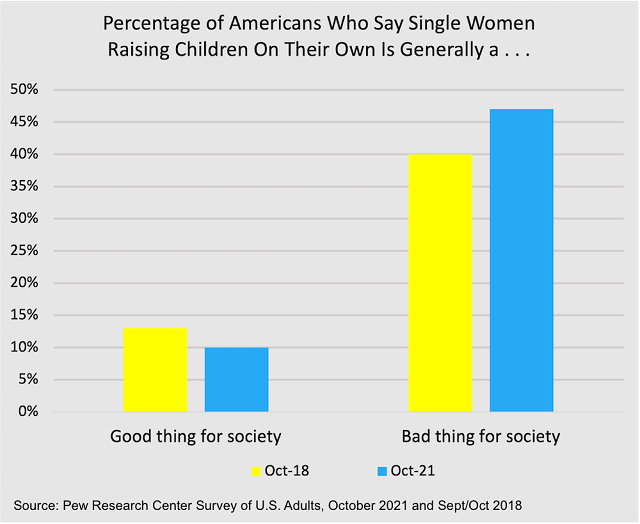

First, a recent Pew Research Center survey that asked American adults about their views on single motherhood and cohabitation revealed some surprising changes. The survey, conducted in October 2021, found that 47% of U.S. adults said single women raising children on their own “is generally a bad thing for society,” an increase of 7 percentage points from 2018.

Younger Americans, men, Republicans, the religious, and Whites were more likely than other groups to express this view, but even so, Pew reports that modest increases also occurred among women, Democrats, and older age groups.

For example, although men are more likely than women to say women raising children alone is bad for society (59% of men vs. 37% of women in 2021), both men and women expressed more negative views in 2021 than in 2018, with a 9-point increase in the share of men and a 7-point increase in the share of women.

Similarly, although Republicans (62%) are more likely than Democrats (36%) to hold this negative view of single motherhood, increases occurred among both groups (9 and 6 points, respectively).

This shift occurred among all adults, but it increased 10-percentage points among young adults ages 18 to 29, according to Pew (from 32% in 2018 to 42% in 2021).

Are Americans simply becoming more “judgmental” about women raising children on their own? Dr. Stanley said he doubts this is the case. Instead, he wondered “if this is the voice of ever-increasing experience with these relationship and family patterns. I would suspect it's more about people experiencing how much harder it is to be a single parent.”

And the pandemic may have played a role, too. “COVID has been much harder on some families than others, but it was surely very hard on single mothers,” he added.

More Americans See Living Together Without Being Married as Negative for Society

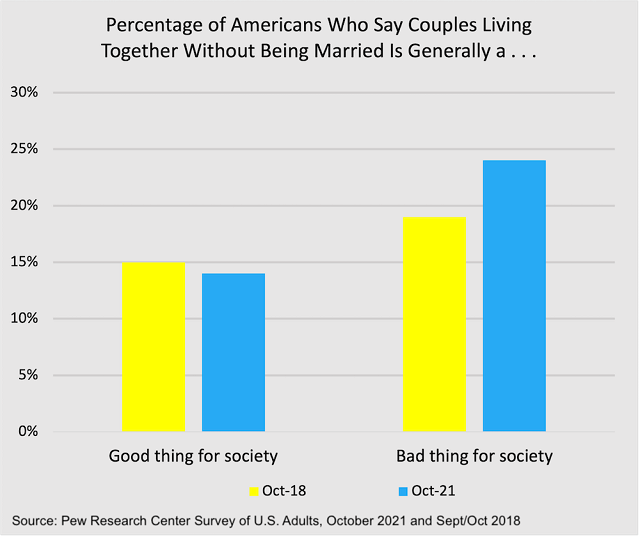

The Pew survey also found that more U.S. adults now say that couples living together without being married is “generally a bad thing for society” compared to three years ago. The share of Americans who view cohabitation in this negative light increased 5 percentage points between 2018 and 2021, from 19% to 24%. Also, the percentage who said cohabitation “doesn’t make much difference” declined from 66% in 2018 to 62% in 2021.

While opinions about cohabitation vary by age, race, gender, and political affiliation, the view that living together outside of marriage is bad for society increased among most groups. When it comes to race, Pew notes:

Since 2018, opinions shifted the most among Black adults, with an increase of 8 percentage points in the share saying cohabitation is bad for society. White adults had a smaller increase of 5 points, while views didn’t change significantly among Hispanic adults.

Although men are more likely than women to say cohabitation is bad for society, there was a modest change in both groups, with a 7-point increase for men and 4-point increase for women.

Dr. Stanley raised the possibility of COVID being in the mix, noting that it is “plausible” that dating couples who moved in together to avoid being separated because of COVID might have had a harder time than those who did so for other reasons.

“An external reason for any major relationship transition is not as good as an internal reason, especially for cohabitation,” Stanley told me.1 External reasons include things like moving in together to save money on rent or for convenience, while internal reasons might include moving in because a couple is growing in commitment and engaged.

“There is evidence that people who move in together for more external reasons don’t do as well,” he said. “And you can imagine that COVID was kind of the ultimate external push for a lot of couples.”

He also offered another theory—that as more Americans have experienced cohabitation, either personally or through watching friends or family cohabit, more people are realizing that living together just does not compare to marriage in terms of relationship quality or stability. That could explain why Pew found a difference based on age. A Pew spokeswoman told me via email, “adults ages 30 to 49, 50 to 64, and ages 65+ were more likely than in 2018 to say [cohabitation] is a bad thing for society.” However, there was no similar shift among 18 to 29-year-olds.

“Maybe part of the Pew story is that more people have cohabited now than ever before, and it is possible some have concluded it was not so great,” he suggested. “Cohabiting relationships last about two years, and it seems likely that some people expected more than they got.” Stanley noted that such an experience-based effect would have occurred less for younger Americans.

Cohabitation Has Plateaued in the U.S.

At the same time that we are seeing an apparent shift in opinions on single motherhood and cohabitation, there are also indications that the increase in cohabitation is slowing down. In a spring 2021 article in the American Sociological Association journal, Contexts, Wendy Manning, Susan Brown, and Krista Payne reported that cohabitation among young women in the United States “may be stalling,” with cohabitation no longer compensating for the continued decline in marriage. "Since 2010 cohabitation rates have stagnated while marriage levels continue to plummet," Manning, Brown, and Payne explained. "In contrast to the trend through 2010, during which cohabitation seemed to replace marriage, recently fewer women formed any type of unions."

They continued, “our findings call into question the widely accepted notion that the U.S. is on a path to reach the nearly universal levels of cohabitation observed in Western Europe.” And they offered this prediction: “In the U.S., if current trends among young adults continue across age groups, cohabitation will no longer supplant marriage. Women will be less likely to form any union instead.”

When I asked Dr. Stanley about the cohabitation plateau, he said “it’s in line with the general trend towards more independence and less connection and rootedness in family relations.” Many of the reasons for this shift in cohabiting behavior, he added, could be similar to reasons for the decline in marriage.

“People are less traditional than they used to be about pairing up, and interest is down,” he pointed out. “Further, peoples’ standards are higher now about what and who they are looking for. Lastly, economic opportunities for women are better, and there is less need for women to seek a co-residential romantic partner unless they really want one.”

And, Stanley emphasized, Americans now have much more experience with cohabitation and may be more "cautious" as a result. "People have seen scores of friends and family members move in together with more of those relationships ending than continuing, so it is possible that the bloom is off the rose a little bit," he said.

On one hand, if these trends continue, American adults holding more realistic views on the very real challenges of both cohabitation and single motherhood could be positive for the well-being of children—especially if these shifts lead to an increase in marital and family stability. However, these changes, including the plateau in cohabitation, along with continued declines in marriage and fertility, could also result in more loneliness and disconnection for both adults and children in the future. Only time will tell.

Alysse ElHage is Editor of the Institute for Family Studies blog.

1. “The study of reasons people give for marrying provides a useful framework for understanding transitions into cohabitation. Surra and Hughes (1997) made a distinction between relationship-driven reasons for marriage (e.g., wanting to spend life together) versus event-driven reasons (e.g., pregnancy). In their work, event-driven reasons were associated with lower marital quality. This distinction fits with commitment theories that differentiate an intrinsic desire to maintain one’s relationship from constraining forces that increase the cost of leaving, thereby encouraging relationship continuance (see Adams & Jones, 1997). In Stanley and Markman’s (1992) theory, the internally based form of commitment is called dedication and the external form is referred to as constraint commitment. Theoretically, Surra and Hughes’s relationship-driven reasons are in line with dedication, and event-driven reasons are similar to constraint commitment.” (From Rhoades, Stanley, and Markman. “Couples’ Reasons for Cohabitation: Associations with Individual Well-Being and Relationship Quality,” Journal of Family Issues, 2009 Feb 1; 30 (2)).