Highlights

- For college-educated women, remote-workers were slightly more likely to be expecting a wedding (28% vs. 22%), but for less-educated women, remote work had large positive associations with marriage plans (24% vs. 14%). Post This

- About 15-20% of women with remote work were trying to become pregnant, compared to just 10-14% of employed women without remote work options. Post This

- If employers continue to allow workers to work from home, weddings and baby showers may be slightly more common in the future. Post This

Newly released provisional CDC data show that birth rates rose slightly in 2021, the first increase in years, and a somewhat surprising turn to many. COVID is well-known to have led to a major crash in birth rates in late 2020 and early 2021, so why did birth rates rise again in late 2021?

The answer is vitally important for understanding the future of work and fertility. If births rose simply because people were stuck at home together, that isn’t replicable in the future: lockdowns can’t (and shouldn’t) go on forever. But if the rapid rebound in births in late 2021 was only indirectly related to COVID, then it could point to a path forward. Maybe COVID triggered some other change in society which, despite the pandemic, allowed more families to have the children they wanted. One obvious change in American society was a massive increase in remote work. Prior academic research focused on Germany has found that increased remote work options may increase fertility, particularly among women with a college education.

To test whether remote work might be at the heart of America’s baby bump, in April 2022, I fielded a survey of 3,000 American women ages 18-44, which included questions about fertility intentions, marital intentions, COVID, and remote work. The sample size of women with remote work options was not extremely large, and thus differences are estimated with a considerable degree of error, but the overall conclusion is striking. In April 2022, women working remotely were about 40% more likely to be trying to have children, be pregnant, or have very recently had children. They were also 20 to 70% more likely to report upcoming marriage plans and they also had more optimistic views of their family futures in general. These effects were generally largest for college-educated women, consistent with the results found in Germany mentioned above.

Remote Work and Fertility

The option to work remotely can enable higher fertility essentially by reducing child care costs. Remote work options allow families more flexibility to deal with unforeseen circumstances (like day care closures or school cancellations, or a sick child), and in some cases even allow parents to cut back on child care utilization: if one or both parents work remotely, one parent may be able to supervise a child at home, depending on the child’s age and disposition, and the parent’s work. These aren’t simple tasks, of course: my own experience is that working remotely while supervising a rambunctious toddler is very difficult. But as difficult as it is, remote work provides this option for those inclined to try it, and at least offers families some flexibility on the margins. However, remote jobs are disproportionately likely to be the kinds of jobs held by highly-educated people. Thus, in general, one proxy for remote work exposure is just “education.”

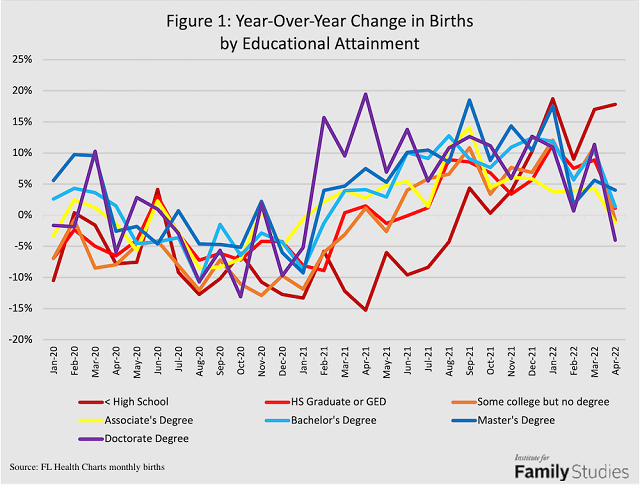

Have births changed in a more positive way for more educated women? Figure 1 below shows the year-over-year change in births to women in Florida (a state which publishes birth data on an expedited timeline) by college education.

Better-educated women saw their birth rates rebound much earlier than other women. In February 2021, births to women with doctorates were up 16% year-over-year in Florida, whereas births for women with less than a high school degree were down 6 percent. That’s consistent with the notion that the shift to remote work might have been beneficial for these better-educated families. So what does our survey from April show?

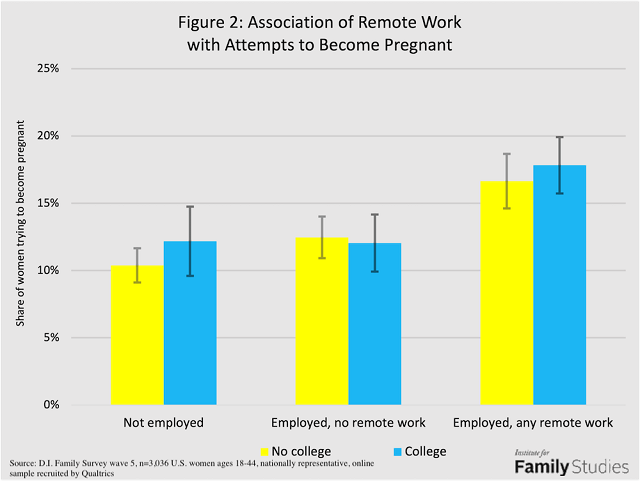

Figure 2 below shows the share of women who said they were trying to become pregnant or about to start trying, by their remote work status and education level.

About 15-20% of women with remote work were trying to become pregnant, compared to just 10-14% of employed women without remote work options. Non-working women includes both unemployed women and stay-at-home wives and mothers. Further analyses suggest that women who work remotely are slightly more likely to be worried about COVID than other women, but also more likely to say that COVID has made them accelerate their family plans or to have a baby: COVID worries did not offset the benefits of remote work. These results hold if pregnant women and women who had children within the last six months are included with the women who are trying to have a baby.

Of course, this isn’t a random treatment, so it’s hard to infer causality, but it doesn’t take much of a logical leap to suppose that the huge increase in remote work options gave a lot of women an opportunity to have the children they wanted to have. COVID may have messed up many life plans, but for the subset of people who were able to shift to remote work because of COVID, childbearing may have become somewhat more attainable.

Remote Work and Marriage

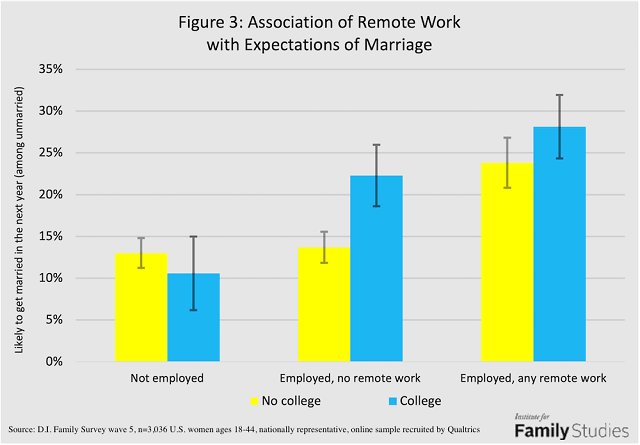

Fertility is an important outcome variable, but not the only one: marriage might also be impacted by remote work. Some people don’t get married because they live and work far from the person they want to marry. Remote work can help solve that issue. Remote work might also give people more flexibility in their time use, giving them space to figure out their romantic lives and invest more in their relationships. To investigate this possibility, the survey also asked women if they were likely to get married in the next year. Figure 3 shows the results.

Access to remote work has a strong association with higher expectations of a forthcoming marriage. For college-educated women, remote-workers were slightly more likely to be expecting a wedding (28% vs. 22%), but for less-educated women, remote work had large positive associations with marriage plans (24% vs. 14%). Again, these differences may not be caused by remote work.

That said, women in the survey were also asked how they felt COVID had impacted their likelihood of marrying. Women who were working remotely were much more likely to say that COVID had increased their likelihood of marriage. There are many reasons for this, but again, it seems plausible that COVID might increase marriage likelihood if it led to expanded remote work options that, in turn, enabled expanded options for living, working, and socializing.

Remote Work and Family Satisfaction

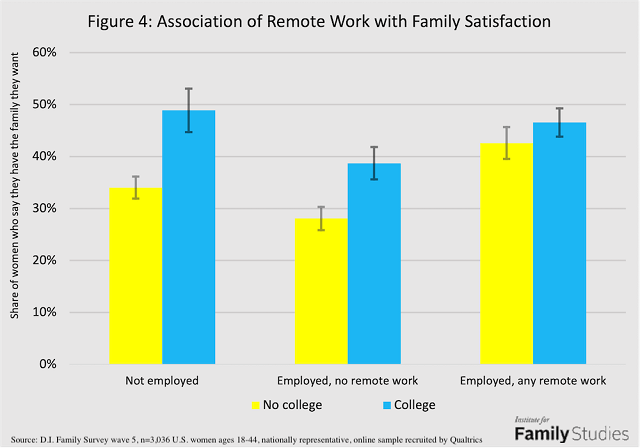

Finally, even if remote work doesn’t push fertility or marriage rates higher, it might make people happier with their family life. More time and flexible options to spend quality time with loved ones could boost happiness in many ways.

Indeed, Figure 4 shows that the share of women who said that they “have the family life they always wanted to have” is 5-20 percentage points higher among employed women who work remotely than among employed women who do not work remotely. Highly-educated, nonworking women are also highly satisfied: these women are likely to be voluntarily nonworking, i.e. stay-at-home-moms, a role likely to yield high family satisfaction.

High satisfaction with family life among remote workers suggests that the positive associations of remote work with marriage and fertility probably are not spurious: these women are happier with their family lives. This happiness might be caused by an expectation of soon having a wedding or a new baby, or the improved family circumstances could possibly lead to more willingness to take the next step in relationships. As with every variable discussed here, causality is difficult to untangle.

But taken together, these results do point to one possible explanation for the rapid rebound in births: expanded remote work. Wider access to flexible and remote work can be kept going long after COVID. If employers continue to allow workers to work from home, weddings and baby showers may be slightly more common in the future. But if employers insist on more physical presence, family life may suffer.

This conclusion is, in fact, obvious. I’ve written extensively about “workism” and its negative effects on fertility elsewhere. In particular, the long working hours that prevail in east Asian countries are almost certainly one of the major reasons for low fertility in Korea, Japan, and elsewhere. Where working hours away from one’s home and family are long—that is, where coworkers and bosses dominate more of life compared to spouses and kin—fertility and marriage suffer. Expanded remote work offers a path to partly reconciling this tension without simply demanding that parents (and especially mothers) abandon their entire earning potential and career ambitions.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.