Highlights

- Could it be that the greatest joy of marriage comes from its duties and obligations and sacrifices rather than its mere pleasures? Post This

- When marriage was most strongly associated with duty and least strongly associated with pleasure, it was also most strongly associated with joy. Post This

- Our debates about marriage and marriage policy will be more fruitful if we can understand exactly what the institution means to people today, and where this meaning came from. Post This

In John Gay’s 1728 drama, The Beggar’s Opera, a rake professes his love to a young woman named Lucy and declares: "I am ready, my dear Lucy, to give you Satisfaction—if you think there is any in Marriage."

I wonder what Lucy thought of this proposal (the drama doesn’t tell us). Would she, and other residents of the 18th century, have viewed marriage as a joyful, satisfying adventure—or as a tedious travail?

We can get a hint of how others may have thought about marriage during this time period by reading Samuel Richardson’s novel Clarissa, published 20 years after The Beggar’s Opera. In this epistolary novel, the heroine is resisting a suitor her relatives wish her to marry. She describes her dim view of marriage in this way:

Marriage is a very solemn engagement, enough to make a young creature 's heart ache, with the best prospects, when she thinks seriously of it! To be given up to a strange man; to be engrafted into a strange family… to be obliged to prefer this strange man to father, mother—to every body—and his humours to all her own—or to contend, perhaps, in breach of avowed duty, for every innocent instance of free-will.

If we trust these perspectives, it would seem that marriage back then was a matter of “avowed duty,” as Clarissa put it, a “solemn engagement” in which one is “obliged” to make great sacrifices. As to whether these sacrifices tended to lead to “satisfaction” for 18th-century paramours, these passages leave us far from certain.

But more than 150 years after Clarissa, in 1905, a character in an E.M. Forster novel (Where Angels Fear to Tread) described his more positive view of marriage, stating: "Ah, one ought to marry! … Not till marriage does one realize the pleasures and the possibilities of life."

Forster’s character does not mention sacrifice or obligation or duty or solemn engagement. Instead, he mentions pleasure. In 2008, economists Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers offered their own perspective on the meaning and purpose of marriage, and how the institution had changed through the centuries:

[T]he key today is consumption complementarities—activities that are not only enjoyable but are more enjoyable when shared with a spouse. We call this new model of sharing our lives “hedonic marriage.”

Hedonic—meaning associated with pleasure—is not an adjective that the characters of The Beggar’s Opera or Clarissa used to describe marriage. If Stevenson and Wolfers are right, marriage has shifted over the centuries from being an institution focused on work to one focused on pleasure. But is their claim accurate? And if it is, what does that mean for us today?

Instead of basing our analysis on vague impressions and handpicked quotes, we can do a more systematic review of more extensive data. For this, we turn to The Corpus of Late Modern English Texts (CLMET), available here. It contains hundreds of public-domain written works spanning the years 1710 to 1920. There is fiction, non-fiction, drama, letters, treatises, and more. Altogether, the corpus contains more than 34 million words.

We can analyze these texts to understand how views about marriage have changed over time. We’ll use a remarkable machine learning tool called word2vec that allows us to make precise, quantitative measurements of the meanings of words. With word2vec, we’ll be able to convert words into numeric vectors that capture the words’ meanings. After converting words to numbers, we can measure the similarity between any pair of words—a numeric measurement instead of only a vague impression. The word2vec scores will always range from 0 (the score we get when comparing completely unrelated, dissimilar words) to 1 (the score we get when comparing perfectly identical synonyms).

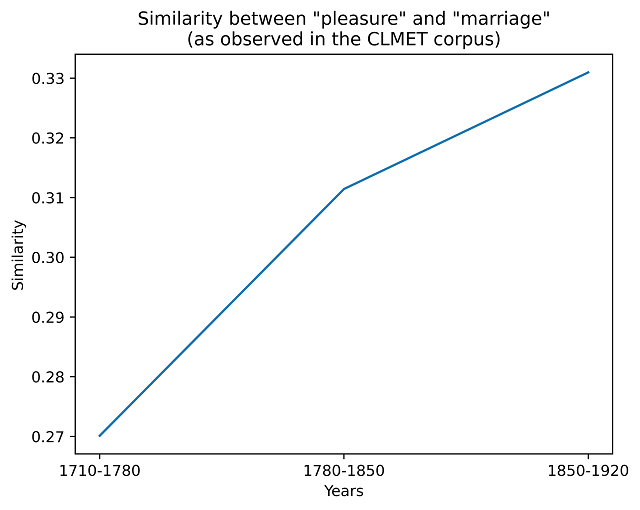

Let’s examine what Stevenson and Wolfers asserted: that marriage has morphed into a “hedonic” institution, one that’s primarily focused on consumption and pleasure. We’ll do this by numerically measuring the similarity between the word “pleasure” and the word “marriage.” We can start by using a word2vec model based on only texts from the 18th century. This will give us an estimate of how similar “pleasure” and “marriage” were according to common perceptions at that time. Then, we can create another word2vec model based on texts from the 19th century, and we’ll use that to measure how similar “pleasure” and “marriage” were perceived to be then. In fact, we can use word2vec models trained on different texts across any time period to measure exactly how the meanings of words shift through history. We see a clear pattern when we look at equal-sized 70-year periods as shown below:

According to the word2vec model and our historical texts, the meanings of “pleasure” and “marriage” appear to become more similar over time, showing a respectable rise from about 0.27 (relatively low similarity in the mid-18th century) to over 0.33 in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (higher similarity for a more hedonic age). This 22% increase in similarity seems to confirm the assertion of Stevenson and Wolfers that marriage has become more closely associated with pleasure over time.

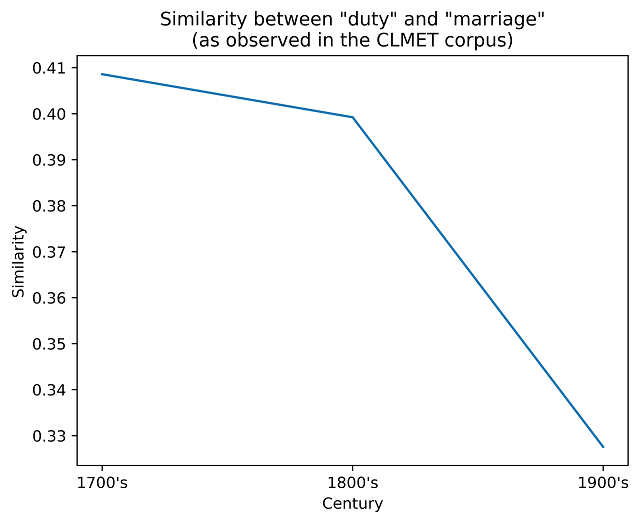

We can do the same exercise for any pair of English words. For example, let’s examine how the similarity between “duty” and “marriage” has changed over time:

The word “duty” has, according to our texts and the word2vec tool, become less similar to “marriage” over time, including a substantial decline in the 20th century. This change also matches trends we can see in history, especially the liberalization of divorce laws. Again, it validates the assertion of Stevenson and Wolfers that marriage has become more about fun and less about obligation and work.

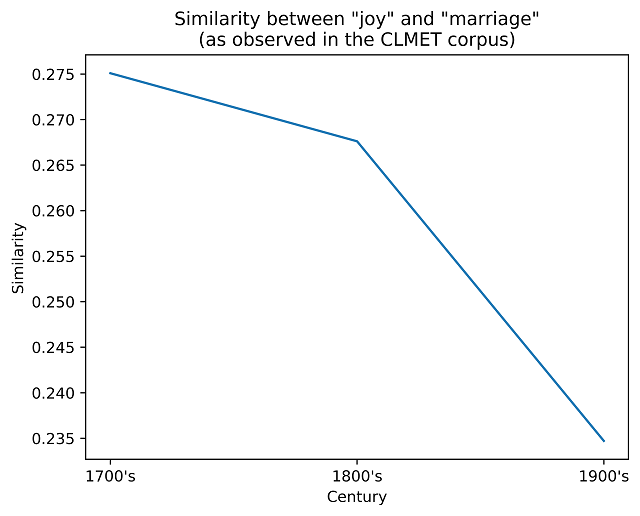

Let’s close with just one more analysis: this time, let’s look at the word “joy.” Sometimes, joy is described as a synonym of “pleasure.” So, if “pleasure” and “marriage” have become more similar over time (as shown in Figure 1), we might expect that “joy” and “marriage” have also become more similar through the centuries.

But joy is not exactly the same as pleasure. “Pleasure” is often used to describe frivolous or short-term delights, and physical sensations rather than mental bliss. “Joy” is often used for more lasting satisfaction, for spiritual rather than physical elation, and a felicitous state of the soul.

When we check the similarity of “joy” and “marriage” in our corpus, we find that, instead of following the pattern of Figure 1 (the increasing similarity of “pleasure” and “marriage”), “joy” follows the declining pattern of Figure 2 (the decreasing similarity of “duty” and “marriage”). See for yourself in Figure 3:

Remarkably, even though “joy” is similar to “pleasure,” we find that just as the association between “pleasure” and “marriage” has increased (Figure 1), the association between “joy” and “marriage” has declined (Figure 3). This is suggestive and exploratory rather than definitive, but there could be a hint here of a secret wisdom in the older conception of marriage: that the time when marriage was most strongly associated with duty and least strongly associated with pleasure, was also the time when it was most strongly associated with joy. Could it be that the greatest joy of marriage comes from its duties and obligations and sacrifices rather than its mere pleasures?

One machine learning linguistic analysis isn’t enough to answer this question. But the idea shouldn’t be a surprise to us. Plenty of philosophers have told us that work and duty and obligation lead to joy for millenia. Consider Aristotle, who described eudaimonia (well-being) in terms of activity: that one must be engaged in virtuous action to be happy, rather than (say) idly laying on the beach forever. Or consider the Zen master, Dogen, who taught that one couldn’t understand the great Buddhist teachings unless one could understand the regular, grueling work of an ordinary cook. Many philosophers of all backgrounds have agreed that to gain the joy of finding your life, you must first lose it—and its pleasures.

History has not stopped, and the meanings of all words will continue to change and drift. Activists may be interested in pushing with or against the tides to nudge words toward some favored meaning, and cause people to view marriage one way or another. Regardless of our preferences about what words should mean, it’s useful to understand what they do mean to most people, and how those meanings have changed over time. Our debates about marriage and marriage policy will be more fruitful if we can understand exactly what the institution means to people today, and where this meaning came from.

Bradford Tuckfield is a data science consultant. His latest book is Dive Into Algorithms.