Highlights

- Parents and married adults are also more likely than childless or unmarried adults to do regular favors for their neighbors. Post This

- Married couples and parents relate to their neighbors in different, and perhaps richer, ways. Recommitting to our neighborhoods may begin with recommitting to marriage and family life. Post This

- Rebuilding civil society will also require a recommitment to our first institution: marriage and the family. Post This

The Joint Economic Committee, which I chair, has released a new report—“The Space Between: Renewing the American Tradition of Civil Society,” which discusses empirical findings about the state of four of civil society’s mediating institutions (the formal and informal social organizations we create to achieve common goals in our interactions with one another): neighborhoods, churches, schools, and voluntary associations. The report is a product of the JEC’s Social Capital Project, a multi-year research effort investigating the evolving nature, quality, and importance of our associational life. In the following post, I highlight some of our report's findings, as well as some of the Project’s further analysis of how marriage and family life relate to civil society.

Though inherited wisdom to many, the symbiotic relationship between marital life and social life has come under heavy scrutiny. In a 2019 essay in The Atlantic, for example, writer Mandy Len Catron argues that traditional marriage offers a false promise of belonging and security that is better found elsewhere in non-traditional arrangements. “Social alienation,” Catron insists, “is so fully integrated into the American ideology of marriage that it’s easy to overlook.” To opt-in to marriage, so the story goes, is to opt-out of community.

The Social Capital Project, however, finds in our new report that we may have reason to see not only the inherent value in marriage, but measurable social value, too—benefits that accrue to spouses and their children, as well as cul-de-sacs, congregations, classrooms, and entire communities. A short march through our mediating institutions helps to highlight its importance.

Neighborhoods

Our report finds that we do less with our neighbors than we once did: we don’t talk as much, we spend fewer evenings together, and we do fewer favors for each other. While some groups report higher levels of neighborliness than others—for example, college-educated adults spend more time with neighbors than do those who do not graduate high school—the overall trend is one of decline.

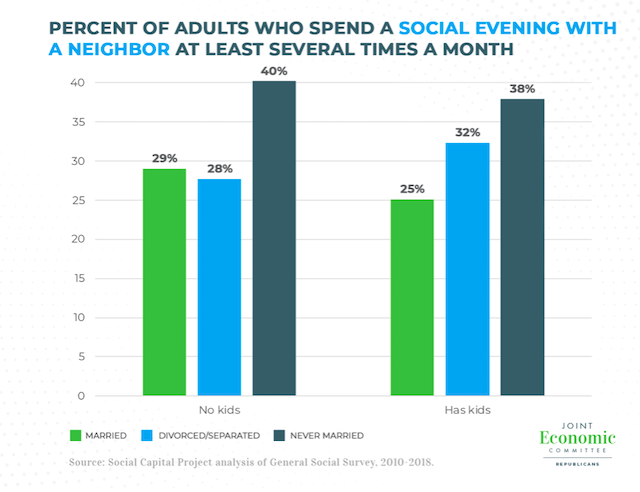

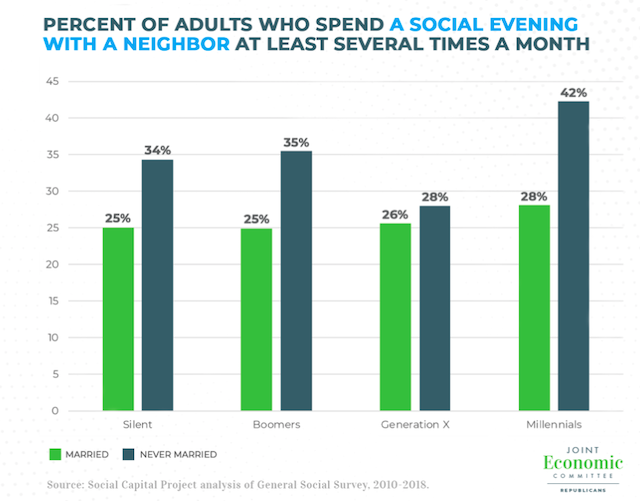

The health of marriage as an institution also appears to shape the way Americans interact with their neighbors. For example, recent data from the General Social Survey (GSS) show that single parents—both divorced and never-married—are more likely than married parents to socialize regularly with their neighbors. Childless, never-married adults are, perhaps unsurprisingly, the most likely to spend several social evenings with neighbors each month. Married parents are the least likely to do so.

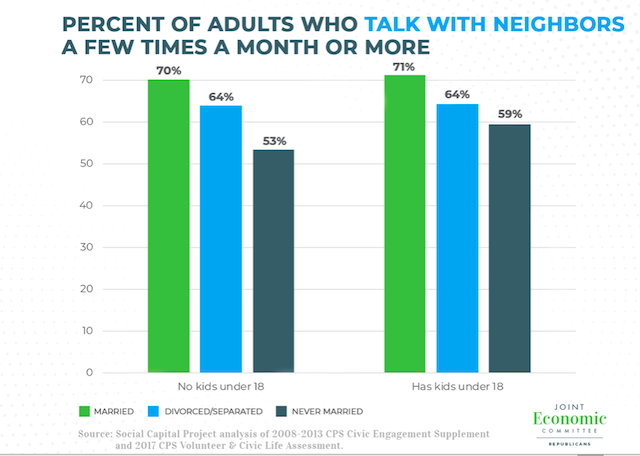

Married adults, however, appear to belong to their neighborhoods in different ways. Recent data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) show that adults who are or have been married are more likely to talk with their neighbors at least a few times per month. Whether they have children appears to have little to no effect on Americans’ likelihood of talking regularly with their neighbors.

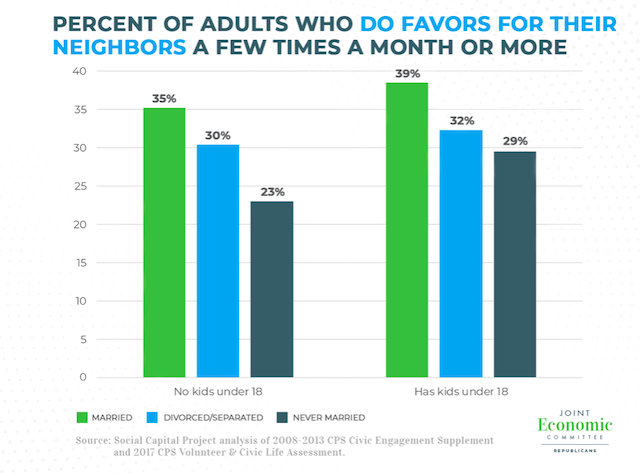

Parents and married adults are also more likely than childless or unmarried adults to do regular favors for their neighbors. Regardless of marital status, parents are more likely than childless adults to assist their neighbors with a favor.

These results may reflect generational and lifecycle differences. The same data show that Millennials (those born between 1981 and 1996) are half as likely as Boomers and Gen Xers to be married. Married adults, for instance, may spend fewer evenings socializing with their neighbors because they spend more time with their spouse. Millennials generally may be more inclined to socialize in the evening than older generations. And it’s possible that chatting with and doing favors for neighbors are interactions that occur more naturally for married couples.

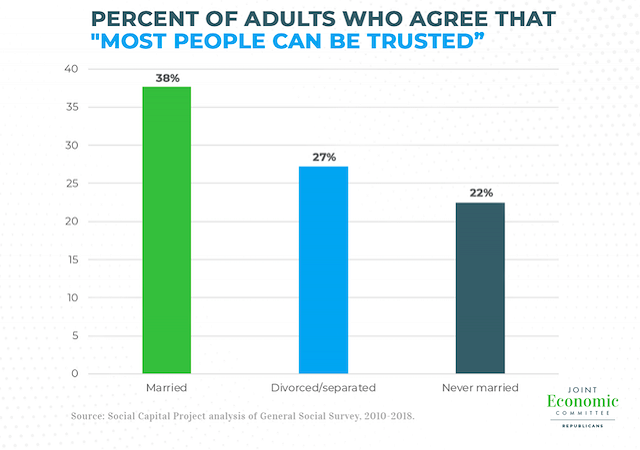

But the results may also indicate a difference in the way that married and unmarried adults see their neighbors. Married couples may see their neighbors less as social companions for a night out than as partners in the project of building a common, family life. Indeed, married couples have consistently been more trusting of others than unmarried adults according to the GSS.

Whether this is a by-product of marriage itself or a happy correlation, the data show that married couples and parents relate to their neighbors in different, and perhaps richer, ways. Recommitting to our neighborhoods may begin with recommitting to marriage and family life.

Churches

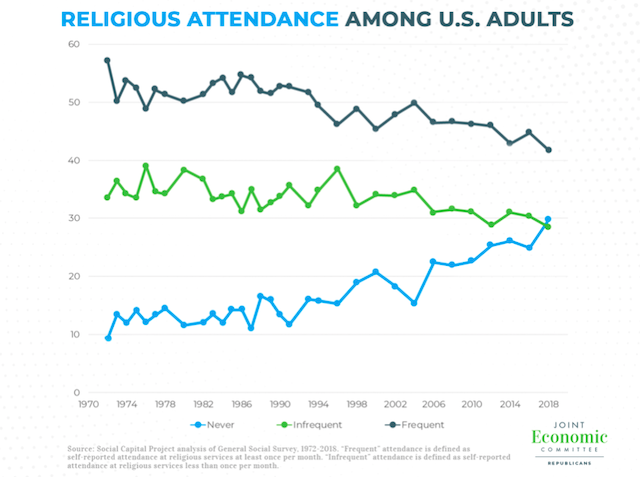

Alexis de Tocqueville described Americans’ religion as “the first of their political institutions,” and much of Americans’ civic engagement still flows through churches today.1 Americans who frequently attend church tend to be happier, healthier, and better spouses and parents, but Americans are, by and large, becoming less attached to houses of worship. The Social Capital Project finds that the share of adults who attend church at least monthly has declined since the early 1970s, while the share of adults who never attend has tripled over the same period.

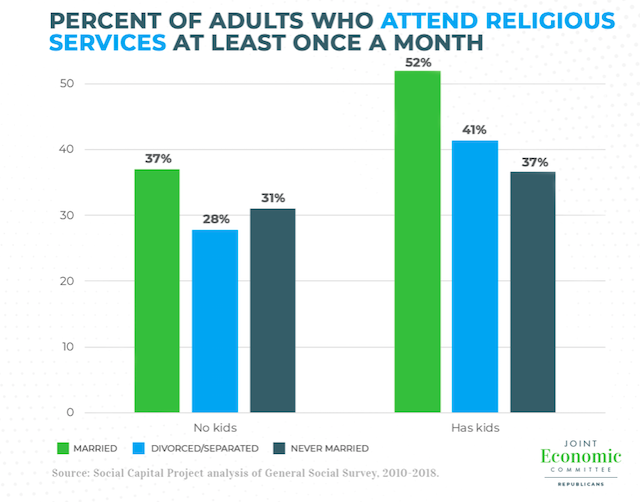

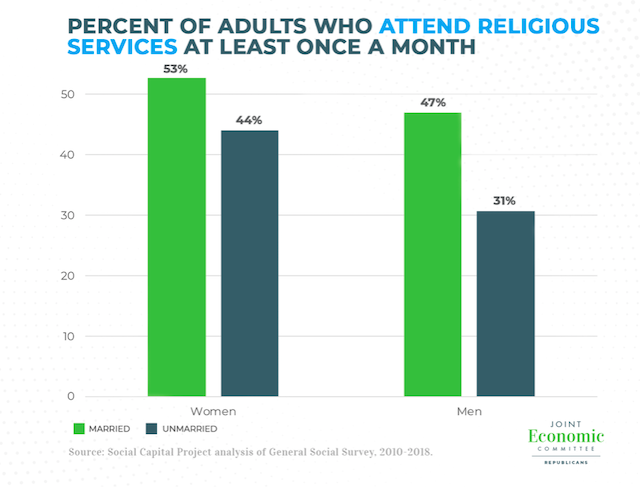

Growing irreligiosity and deinstitutionalization have affected virtually all demographic groups, including both married and unmarried adults. Married adults, however, are most likely to attend church frequently. Being a parent is associated with higher levels of church attendance regardless of marital status.

Women attend church more regularly than men. As IFS Research Fellow Lyman Stone has shown, male church attendance has fallen for all major U.S. religious groups. Yet marriage makes a difference across gender lines—and especially so for men.

Secularization and deinstitutionalization are long-term trends with deep-seeded causes. Marriage, however, remains one of the best predictors of religious membership. Those committed to the institution of marriage tend to be committed to institutions of faith as well.

Schools

Schools constitute a critical part of the community fabric for many towns and neighborhoods across America. Beyond the classroom, schools often serve as a nexus of community life and deliver social services and other goods. Research has shown that the benefits students receive from meaningful civic engagement in school persist into adulthood. Parental involvement matters, too, and is associated with higher school quality and better student outcomes.

Data from the U.S. Department of Education show that parents and guardians have become more actively involved in their children’s schools over the last two decades. These patterns reflect recent trends in child-rearing and family formation. American parents may have become more involved in their children’s education, as academic achievement more strongly determines one’s socioeconomic prospects in a meritocratic system. They may also have more time to invest in their children more generally as the typical American family shrinks.

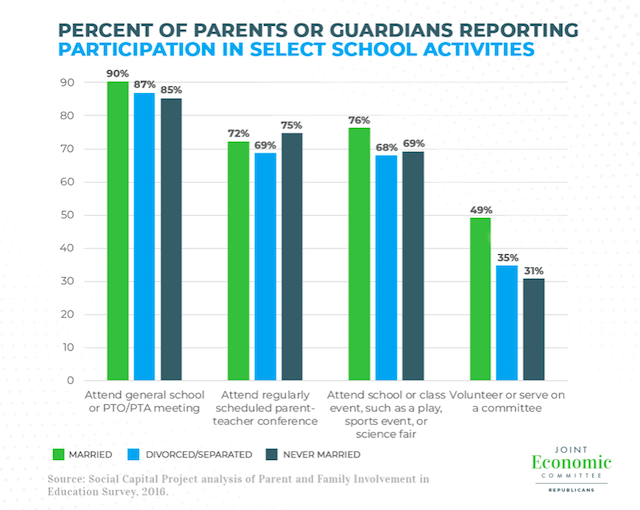

Marital status does not appear to have much effect on participation in less intensive activities associated with children’s academic performance—school meetings, parent-teacher conferences, and the like. Married adults, however, are much more likely than divorced, separated, or never-married parents to fulfill time-intensive roles, such as volunteering or serving on a committee. This suggests that married parents may be either more able or willing to partner with schools as institutions, assuming functions or membership rather than just oversight.

Voluntary Associations

A portrait of American civil society would be incomplete without voluntary associations—the clubs, charities, leagues, and societies that were once a staple of our common life. These local groups offer a diversity of functions and flavors, but they have conventionally secured both communal benefits of membership and solidarity as well as the tangible benefits of mutual aid and material support to those in need.

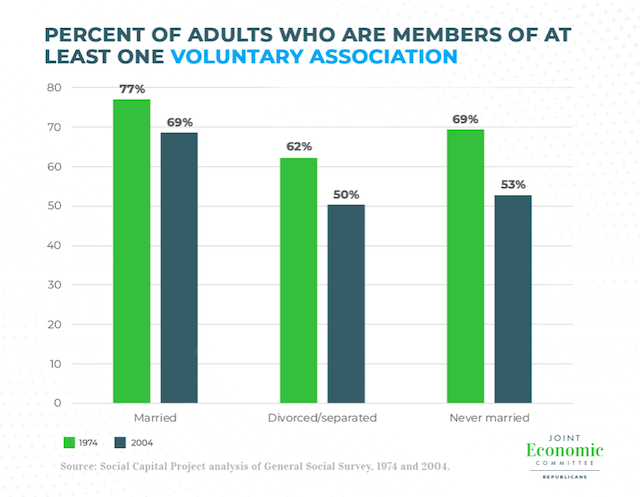

For the last half-century, membership in these largely chapter-based organizations has fallen with the concomitant rise of national, professionally managed ones. Data from the GSS show that formal membership in at least one of sixteen types of voluntary associations fell from 75% to 62% from 1974 to 2004, the most recent year of available data. The decline has been especially pronounced among fraternal organizations, veterans groups, and labor unions.

The decline has also been more pronounced among divorced, separated, and never-married adults. Married adults have been and continue to be the most likely to belong to at least one voluntary association. From 1974 to 2004 the share of married adults who belonged to at least one voluntary association fell by 8 percentage points. Meanwhile, over the same period, membership among divorced or separated adults fell by 12 percentage points, among never-married adults by 16 percentage points.

Recent data suggest that these trends have not improved. For instance, the Civic Engagement Supplement to the CPS indicates that, by the late 2000s, the share of American adults who never attended club meetings had risen to three-fourths.

The steady erosion of membership in voluntary associations has been too widespread and protracted to be attributed to a single cause. The trend among married adults, however, is suggestive: as with neighborhoods, churches, and schools, adults committed to the institution of marriage may also be more committed to this mediating institution, reflecting either a greater willingness or ability to make sacrifices for, and partner with, others.

Conclusion

Understanding more fully the decline of our mediating institutions will require further study. This Social Capital Project report seeks to deepen that understanding. The plight of American civil society is attributable to a number of causes—some social, some cultural, some economic, and some political. The public policies necessary to address it are similarly multifaceted. It will require a change in both the disposition and focus of policymakers at all levels of government. Our report outlines four principal objectives—addressing crowd-out, spurring local innovation, empowering local decision-making, and rebuilding the mediating institutions—as well as specific policy reforms to support them.

But as the trends described above indicate, rebuilding civil society will also require a recommitment to our first institution: marriage and the family.

U.S. Senator Mike Lee (R-Utah) is Chairman of the Joint Economic Committee and author of “Our Lost Constitution: The Willful Subversion of America's Founding Document.”

1. Out of convenience and given the predominance of Christianity in America, the Project uses the common term “church” as shorthand for any house of worship.