Highlights

I’d be surprised if anyone actually supports a federal income tax code that penalizes parents if they get married. Yet marriage penalties in the tax system exist, especially for low-income families eligible for the earned income tax credit (EITC). The EITC is an important anti-poverty program, reducing the number of people in poverty by roughly 6 million in 2013. As a refundable tax credit for working families and individuals, it supplements low wages by up to $5,548 for a family with two children and $503 for childless workers as of tax year 2015.

Few proposals aimed at eliminating marriage penalties are taken seriously, because fully remedying penalties is costly, some people don’t believe penalties actually affect marriage decisions, and others simply don’t believe that the penalties are very large.

This debate is made more difficult because of data limitations. A good deal of existing research highlights potential marriage penalties (in the EITC and the tax code more broadly) by applying tax code provisions to various hypothetical scenarios of couples and their earnings. These efforts tell us potential penalties, but do little to illustrate actual penalties real couples face. Assessing real-life situations is difficult, because surveys that link parents who are not married and not living together are rare.

But in a recent study, I analyzed data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, which does link unmarried parents, to identify the actual EITC penalty parents in urban areas might face if they choose marriage. The Fragile Families Study is a longitudinal survey of parents who had a child between 1998 and 2000 in urban areas. It oversampled unmarried parents and as a whole is representative of this group in cities with a population of over 200,000.

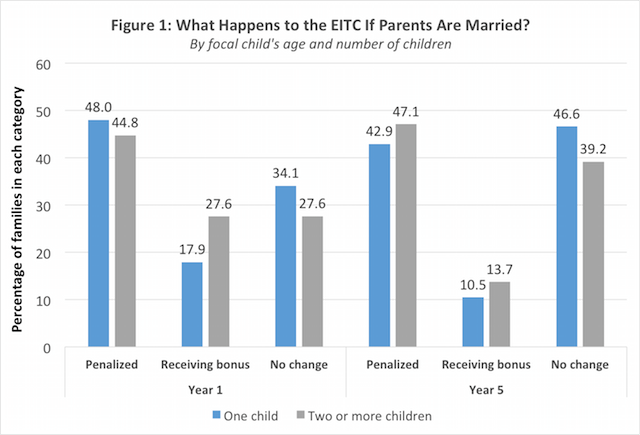

Although the analysis remains speculative, the results suggest that more low-income parents face an EITC penalty than a bonus if they choose marriage. The figure below shows that between 40 and 50 percent of parents with a one-year-old faced a penalty; about half as many would experience a bonus. And when the child who was the focus of the study was five, even fewer experienced a bonus. This was consistent for families with one child and two or more children.

Source: Author’s calculations of Fragile Families data wave two and wave four. Marriage implications related to the EITC were estimated for all couples, no matter their marital/living status. This means that married couples in the Fragile Families data were also assessed to determine the penalty/bonus that they faced because of their marriage. For year one, n = 3,253 and for year five, n = 2,923.

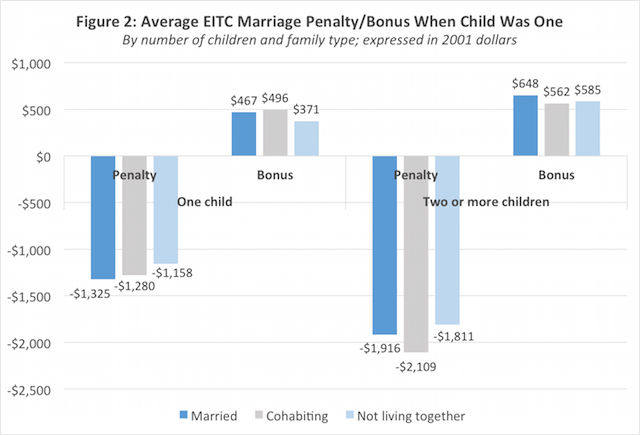

The analysis also revealed that the penalties were quite large. The figure below shows that when the child was one, penalties ranged from $1200 to $2100 depending on the number of children and living situation (in 2001 dollars). Marriage bonuses, for the smaller subset of families who received them, ranged from about $400 to $500. And when the child was five, a similar pattern was seen with penalties and bonuses roughly the same sizes.

Source: Author’s calculations of Fragile Families data wave two. Marriage implications related to the EITC were estimated for all couples, no matter their marital/living status. This means that married couples in the Fragile Families data were also assessed to determine the penalty/bonus that they faced because of their marriage.

For low-income families, $1,000 to $2,000 can obviously represent a fairly large portion of household income. I also analyzed whether expanding the EITC currently available to childless workers (workers not living with children) would make marriage penalties worse. Not surprisingly, they do, but by fairly small amounts.

These results demonstrate that EITC marriage penalties have real implications for the finances of low-income families. We don’t know the extent to which parents factor the EITC into their decisions around marriage. Qualitative work suggests the answer is not very much. But EITC penalties send the wrong message and may contribute to a culture that minimizes the importance of marriage. That seems like the wrong role for our federal income tax system.

Angela Rachidi is Research Fellow in Poverty Studies at the American Enterprise Institute, where she studies the effects of public policy and existing support programs on low-income families.