Highlights

Decision making about sexual practices and family formation has become complex for those who identify with counter-cultural and sub-cultural groups (or who simply ascribe to traditional views about sexuality and family life). The widening gap between modern and traditional family norms and values has created an internal dissonance between societal and group specific beliefs about many aspects of sex, marriage, and family.

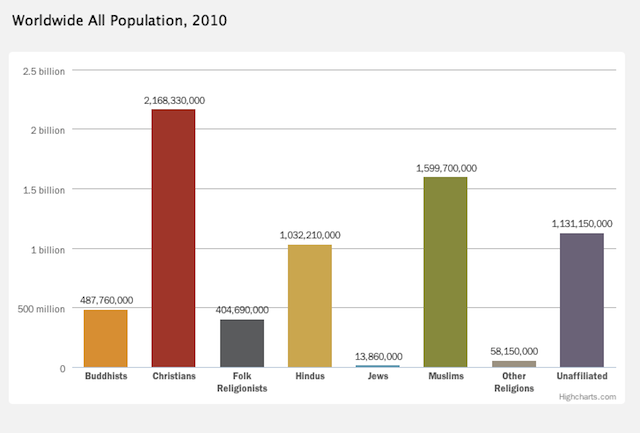

The majority of the world’s population, however, still identifies with a religious group and 80 percent of young adults hold marriage to be an important part of their life plans, even as practices such as cohabitation have become normative. This suggests that there is a dissonance between many young adults professed beliefs and goals and their practices. It is unclear, for example, how many young people and adults know how cohabitation could impact their future marriage. Presently, it has been found that cohabitation increases a couple’s chances of breaking up or not marrying. If they do marry, it decreases the quality of their marriage, while increasing their risk of divorce. Greater awareness about both the benefits and consequences of the current normative practices in the realm of sexuality and family life, and about the ways religious beliefs influence adherents’ family formation decisions will be vital in assisting individuals to meet their relationship and marital goals.

Source: The Global Religious Futures project

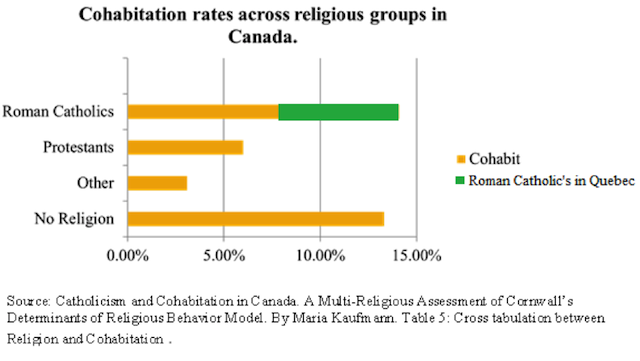

I have devoted the majority of my professional and academic pursuits to examining how one’s professed religious belief influences family formation patterns (specifically individual’s likelihood of cohabitating). In my own research, I have examined the cohabitation patterns of Catholics, Protestants, and those who identified as having no religion, in Canada. Ultimately I found that although Catholics held the most firm beliefs regarding the behaviors encompassed in cohabitation (extra-marital sex and possibly contraceptive usage), they did not exhibit lower rates of cohabitation than other religious groups (in this case Protestants and those who do not affiliate with a religion). What is more, Catholics’ odds of cohabitation were at times among the highest of the religious groups observed or occasionally similar to that of respondents of no religion.

Why was this case? Why was the only group with established doctrine about the behaviors encompassed in cohabitation (as something not beneficial and immoral), similar to individuals that don’t affiliate with a religion in practice?

First, my results were specific to Canada’s unique cultural factors and regional factors. Canada’s figures are largely skewed by the many Quebeckers that identify as Catholic (almost half of the Catholics in my sample resided in Quebec) but don’t live religious lives. Second, mirroring trends in the global decline of religion, individuals in Canada may be developing more liberal views of religion. So while many may report religious affiliation, few exhibit religious behavior in all areas of their lives.

Beyond my own research on the subject, much of the past and current research about religion and family formation indicates that religious factors have a significant influence on adherents’ behavior in matters of sexuality and family life and that often religion decreases positive attitudes towards cohabitation and deters progressive family formation practices (such as cohabiting).[1]

Among more recent findings, a report about the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth by Goodwin, Mosher, & Chandra found that “60% of non-Hispanic white women for whom religion was ‘very important’ in their daily lives were currently married, compared with 36% of white women for whom religion was ‘not important’. Similar patterns in marital or cohabiting status by importance of religion were found for non-Hispanic men and women, black men, and Hispanic men and women.” Similarly, Eggebeen and Dew found that Catholics who attended Church regularly and displayed “fervor” were actually less likely to cohabit than “devout” Conservative Protestants. Furthermore, Thornton, Axinn, and Xie found that the higher the religiosity of one’s family, the greater the likelihood of marrying and the lower the likelihood of cohabiting: “Young adults who are from more religious families and are more religious themselves” they found, “have substantially higher marriage rates and lower cohabitation rates than young adults who are less religious and come from less religious families.” Finally, Gault-Sherman and Draper found that religious networks and communities and the religiosity of one’s geographic location influences union formation negatively, and that the degree at which religion influences union formation patterns varies by geographic location and religious group. Evangelicals were less likely to cohabit and being a Southerner and Christian influenced union formation patterns the most.

Given that past literature on the topic suggests that religion has a notable influence on adherents’ family formation practices and that religion is associated with more traditional attitudes and family formation structures, going forward it will be particularly important to assess what specific qualities of religious factors contribute to the noted consistencies between adherents’ beliefs and behavior. For instance, in the case of Eggebeen and Dew’s finding about the religious factors that point to the different cohabitation rates between Catholics and Conservative Protestants (see above), what about displaying “fervor” aids individuals to behave counter-culturally? How does religious fervor come about? Research models that include the greatest number of religious measures, such as Cornwall’s model, which consist of: “Group involvement, belief-orthodoxy, religious commitment, religious socialization, and socio-demographic characteristics,” could allow scholars to determine the most accurate results about the role that multiple facets of religiosity have on people’s lives. Additionally, given that the Catholic Church is not the only religious group that does not view the behaviors encompassed in cohabitation as beneficial, [2] future studies should aim to include as many religions as possible and should differentiate Protestants groups by denomination. Doing so could help to clarify how the specific religious beliefs of a group influence their behavior.

As cohabitation and other changing practices in the realm of sexuality and family life, become more prevalent in Western countries, further research about the association between religion and family formation will be of great importance for both scholars who study culture, religion and family, and for the many groups that hold norms, values, and beliefs that are in opposition to these societal trends. A greater understanding of the ways members of religious groups respond to the dichotomy between societal and group-specific beliefs and their own family formation practices could enable religious leaders to assess modes of aiding their members in reconciling the contradictions they face daily between larger society and their beliefs (for instance: program development to help their adherents understand why their group upholds their specific norms, values and beliefs), and could empower individuals with the information they require to make informed decisions about their sexuality, marriage, and family life.

[1] Wu, Z., & Balakrishnan, T. R. (1992). Attitudes towards Cohabitation and Marriage in Canada. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 23(1), 1- 12.

Ellison, C.G., Wolfinger, N.H., & Ramos-Wada, A.I. (2012). Attitudes Toward Marriage, Divorce, Cohabitation, and Casual Sex Among Working-Age Latinos: Does Religion Matter? Journal of Family Issues, XX(X), 1-28.

Thornton, A., Axinn, W. G., & Hill, D. H. (1992). Reciprocal effects of religiosity, cohabitation, and marriage. American Journal of Sociology, 98(3), p. 628-651.

[2] A couple of Protestant churches, such as: some Baptist and Evangelical Lutheran churches, and other religions, such as: Islam and Mormonism also do not view the behaviors associated with cohabitation as favorable.