Highlights

- The events of the last 18 months have motivated partisans on both sides to lean into their prior social models: Republicans by becoming even more familistic and marriage-minded, Democrats by becoming more cautious about these life decisions. Post This

- COVID-19 may in fact nudge different racial and ethnic groups slightly closer together in terms of their marriage behaviors. Post This

Editor's Note: The following essay is excerpted from the new AEI/IFS/Wheatley report, The Divided State of Our Unions: Family Formation in (Post-) COVID-19 America.

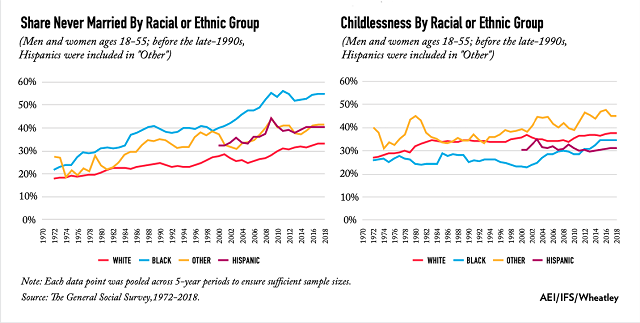

To put attitudes toward family formation in historic perspective, we also calculated the share of men and women ages 18-55 (the same age range as the surveys in this report) who reported never having had any children or never having been married in the General Social Survey from 1972 to 2018. In some areas, there have been growing divides across the same social and cultural gaps identified in our survey, and thus COVID-19 appears likely to intensify the process of cultural polarization of the family. In other cases, the pandemic may end up moderating some differences.

Trends in Marriage and Childlessness, by Partisanship and Religious Attendance

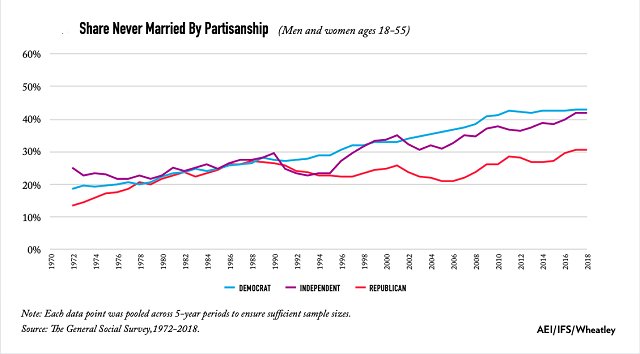

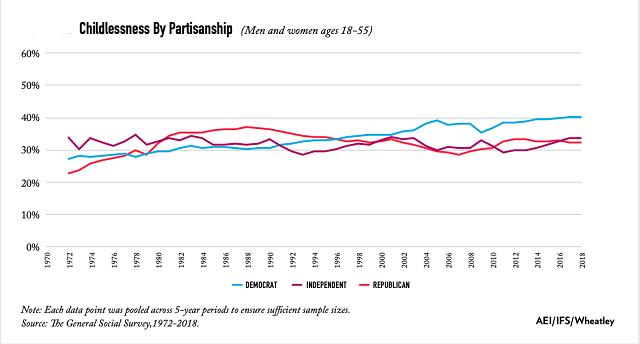

When it comes to partisanship, there has been a persistently growing divide in marriage and childbearing between Democrats and Republicans. Over time, Democrats are getting married later and less, and have become less likely to have children. Republicans, on the other hand, have seen their marriage and childbearing rates remain largely stable. These trends match the reported changes we found in our two survey waves: Republicans had more positive desires for marriage and childbearing as a result of COVID than Democrats.

Thus, it seems likely that COVID will intensify family-model differences across political lines. The events of the last 18 months have motivated partisans on both sides to lean into their prior social models more heavily: Republicans by becoming even more familistic and marriage-minded, Democrats by becoming more cautious about embarking on these life decisions.

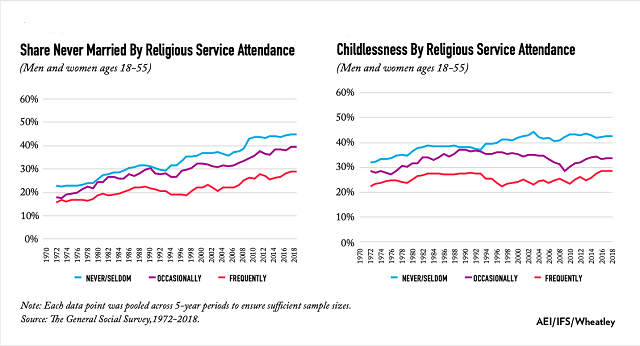

Turning to religion, there is evidence of a similar intensification of pre-existing trends. For decades, there have been large differences in marriage and childbearing behavior between Americans with different religious behaviors, with those differences growing larger recently. More religious people get married earlier and are more likely to have ever been married later in life. They also tend to have more children. In the 1970s and 1980s, these differences were much smaller than they have been since 2000. Our survey indicates these differences are likely to get even larger, as religious people respond to the challenges of the last 18 months by doubling down on the stable-in-times-of-chaos bonds of marriage and family, even as more secular Americans usually see chaotic times as bad times to start a marriage or family.

Trends in Marriage and Childlessness, by Education

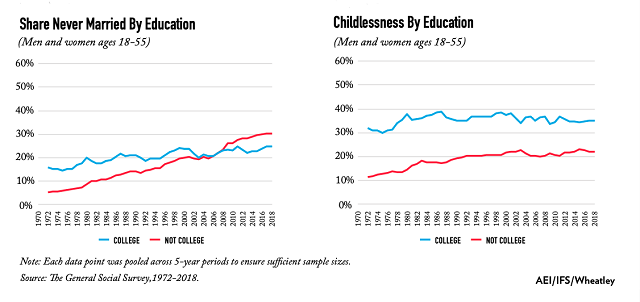

Whereas we found increasing polarization along religious and partisan lines, we find a more mixed story along educational or class lines. Since the 1970s, working-class Americans have changed from being more likely to marry to becoming less likely to marry than college-educated Americans. COVID-19 may intensify that divide, as Zoom-class workers use their newfound flexibility to start married lives, while “essential workers” on the frontlines deal with deteriorating work environments and greater risk of infection. But college-educated Americans have also tended to have fewer or no children. Still, childlessness has almost doubled among the less educated from the 1970s to the present, and the fallout of COVID-19 seems more likely to drive childlessness higher among those with the least resources. This might further reduce the parenthood gap between blue-collar and digital workers.

Trends in Marriage and Childlessness, By Race and Ethnicity

Finally, when it comes to racial and ethnic divides, the story may be one of reduced polarization. Black and Hispanic women are most likely to report that COVID-19 increased their desire to wed, and they are also among the most likely to have never been married. COVID-19 may in fact nudge different racial and ethnic groups slightly closer together in terms of their marriage behaviors. In terms of childbearing desires, Hispanics had the largest decline due to COVID-19, but also already had the lowest childlessness, which could again serve to reduce the gap in childlessness between Hispanics and Americans of other ethnic groups.

Thus, COVID-19 likely intensified family differences between religious and political groups that have been growing in recent decades. But the story is more complicated when we turn to class, race, and ethnicity. Across socioeconomic class, marriage differences seem likely to grow in line with recent history, while differences in childbearing may shrink. But among racial and ethnic groups, COVID-19 may have ended up reducing the extent of difference in family aspirations. Broadly, these changes speak to the extent to which American society is realigning itself, with disputes about essentially cultural, religious, or ideological views becoming more socially salient. By contrast, differences along racial, ethnic, and class lines may be muddying.