Highlights

When a biological father joins a lone-mother family after his child is born, what impact does his presence have on child well-being, and how does this compare to a stepfather joining the family instead? Moreover, if the biological father joins the family but then leaves, what impact does his exit have on the child? These are some of the questions considered in a recent study that followed the family trajectories of about 1,000 children born to lone mothers in the United Kingdom.

As co-authors Elena Mariani, Berkay Ӧzcan, and Alice Goisis of the London School of Economics acknowledge, a large body of research has examined the impact of family stability and structure on children to find that children do poorly when a biological father is absent. But most of these studies compare children in single-mother families to those in stable, two-parent families. What their study offers is a look at how four common trajectories of lone-mother families in the UK compare to one another, which, they say, is the first study to do so outside of the United States. They show that how these children fare on key health indicators during the first seven years of life depends, in part, on whether their biological father or a stepfather joins the family.

The authors relied on data from the UK Millennium Cohort Study (MCS), following MCS children born to lone mothers for seven years to measure how they did on three health indicators based on their family trajectory. Importantly, they defined “lone mother” as one who “was neither married nor cohabiting when the child was born.”

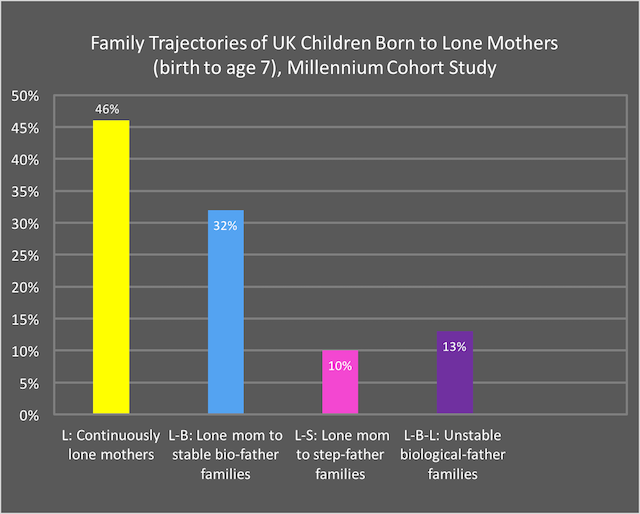

The study sample included a total of 7,330 children from the MCS divided into two groups: 1) children born to lone mothers (a total of 1,169), and children born to stable biological parents, who served as the comparison group. The children in the lone-mother group were then divided into four groups that represent 82 percent of the family trajectories in the UK for lone mothers, according to the authors (see figure below). They then measured child well-being by three outcomes at age 7: health (child obesity); cognitive development (math and reading skills); and socio-emotional well-being [internalizing (anxiety, depression) and externalizing behaviors (attention deficit, uncooperative)].

Source: Table 1 in E. Mariani, et al., "Family Trajectories and Well-Being of Children Born to Lone Mothers in the UK," May 2017

The study found that children born to lone mothers enjoy the best outcomes when their biological father joins the family—if he stays. Indeed, compared to the children of continuously lone mothers, children who went from lone mother to stable biological-father families fared nearly as well as children born and raised in intact biological-parent families on every outcome in the study except for one (the externalizing scale). On the other hand, children who lived with a stepfather or children whose biological father entered but then exited the family experienced similar outcomes to the children of continuously lone mothers.

Obesity. Similar to other studies linking single-parent families to child obesity, such as this recent one from Australia, the UK study found a strong negative association to child obesity from living with a biological father either in a stable or unstable union. Stepfathers did not have a similar influence on reducing child obesity—a finding the authors speculate might be related to a biological father’s ability to better set and enforce rules.

Reading Skills. When it came to reading skills, stability and structure were key. Children in unstable biological-father families and children in stepfather families had worse reading skills than both children raised by continuously lone mothers and those in stable biological-father families (who had the highest reading skills of all the lone-mother family groups).

Depression/Anxiety. The study found only “small differences” in socio-emotional well-being for children in stepfather families compared to those in continuously lone-mother families. In fact, the only family trajectory for the children of lone mothers where there was a positive association for children’s internalizing behaviors (i.e., less anxiety and depression up to age 7) was in stable biological-father families. “This result is consistent with a stable increase in family resources associated with the entry of a biological father, especially in terms of emotional support to the mother and the child,” the authors note.

Behavior. Finally, children born into biological-parent families had the fewest behavioral problems compared to all the children born to lone mothers in any trajectory. However, the study found no “variation” in behavioral problems between the children in the different lone-mother families. “In other words,” the authors explain, “the positive association between behavioral problems and living with a lone mother holds, regardless of whether a father figure subsequently enters or exits the household.”

This finding appears to be inconsistent with other studies, such as a U.S. study by Colter Mitchell, Sara McLanahan, and others, which found that the entrance of a biological father is associated with “lower anti-social behavior among boys,” while the entrance of a stepfather is linked to “higher anti-social behavior for boys with certain genetic variants.”

In many ways, the UK study confirms what we already know—that the best family structure for children is to grow up in with both their biological parents in a stable union. It also provides us with further evidence of the unique and irreplaceable role of biological fathers in fostering child well-being—even when he joins a family after a child is born.

Still, the study contains at least one noteworthy weakness: it groups cohabiting and married mothers together, which the authors explain they did to "maximize" their sample size and because cohabiting unions are more “marriage-like” in the UK. This means we do not know whether the biological fathers who joined and then exited the families were married to or cohabiting with the mothers at the time. It’s an unfortunate omission since married parenthood offers children the best chance at a stable family life. As the 2017 World Family Map showed, married-parent families are more stable than cohabiting parent families—even in the UK where this study was based. Likewise, research shows that fathers tend to parent better within marriage.

Despite this flaw, the study makes an important contribution to our knowledge of the different paths that lone-mother families can take after a child is born, and how each path can positively or negatively influence child well-being. As co-author Dr. Berkay Ӧzcan noted, the results underscore “the important positive influence a biological father can have on his child’s life if he joins and stays with the family unit” (emphasis added). Of course, that outcome is more likely to occur with marriage, which is still the best instrument we have for connecting fathers to their children.