Highlights

- The evidence could not be clearer that kids are far more likely to flourish when they have the privilege of being raised by their own married parents. Post This

- Bruenig’s argument about work obscures an important point: single moms were more than 8 times less likely to be working in 2022 compared to married parents. Post This

- Utah’s youth deserve to know the proven pathway to a better life: the success sequence. Post This

The science could not be clearer: On average, the children of married parents are more likely to experience happier, healthier and more successful lives. Brookings Institution scholar Melissa Kearney powerfully underscores this truth in her new book “The Two-Parent Privilege,” writing, “The decline in the share of U.S. children living in a two-parent family over the past 40 years has not been good — for children, for families, or for the United States.”

But for policymakers in Utah, what are the practical implications of this truth? That is, what can they do to keep families strong and stable across the state?

As I have written previously with others, a big step Utah could take is to educate its young people about what is known as the success sequence. This three-pronged sequence encourages young adults to get at least a high school degree, work full time in their 20s, and marry before they have any children. Our recommendations include incorporating the success sequence into public school curricula in Utah, including it in premarital educational information and broadcasting PSAs about it.

But the success sequence — especially its incorporation of marriage — is not without its critics. Leftists like Matt Bruenig, president of the People’s Policy Project, claim that all that really matters is having a full-time worker in the household — that there is no special magic about marriage when it comes to protecting families from poverty. He says, “Work does all of the work” in accounting for the sequence’s effect on poverty. Others, like Nicole Sussner Rodgers, the executive director of Family Story, argue that marriage does not provide any unique advantage for the welfare of children.

These criticisms, however, could not be more unmoored from the latest social science. It could scarcely be clearer that marriage per se matters for families’ economic well-being, contra Bruenig, and for the well-being of children, contra Rodgers.

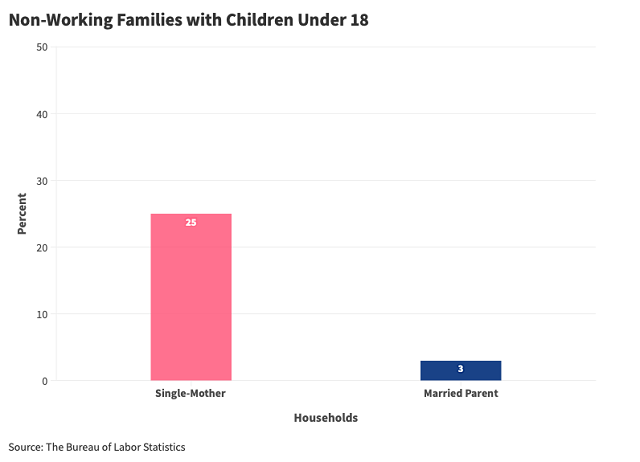

Let’s take money first. Research shows that millennials who follow the success sequence are 60% less likely to experience poverty and have twice the odds of achieving the American dream, even controlling for their work history. Moreover, Bruenig’s argument about work obscures an important point. The latest data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us that single moms were more than eight times less likely to be working in 2022 compared to married households. This means it’s easier for married couples to support a worker, which is one big reason they are much less likely to be poor than families headed by a single parent. Not surprisingly, families headed by single moms are five times as likely to live in poverty as married-couple families.

When it comes to child well-being, let’s consider stability first. We know that kids thrive on stable routines with stable caregivers, and married parents typically provide a much more stable environment than cohabiting or single-parent households. For example, kids born to married parents are twice as likely to still live with both parents at age 10, compared to their peers whose parents cohabited. Cohabitating parents who aren’t married when their child is born are two to four times more likely to separate than couples who are married.

Changes in family structure also often come with changes in housing, and kids are more likely to have difficulty in school and life if they move from one home to another frequently. Single and stepparents are twice as likely to move their family as married couples. Frequent moving explains 18% of the academic underperformance of kids with single parents, and 29% of the disadvantage for kids in stepfamilies. These vulnerabilities, in turn, help explain why children from nonintact families are about half as likely to graduate from college and twice as likely to land in prison. There’s no question that Rodgers is off the mark here in discounting the link between marriage and the welfare of children.

All of this isn’t to denigrate the sacrifices and successes of single parents. Many single parents across the nation put in long hours and tiring days, working selflessly for their children. I was raised by a single mother and turned out OK — and the same could be said for figures like Barack Obama and Jeff Bezos. But as a sociologist, I can also tell you the evidence could not be clearer that kids are far more likely to flourish when they have the privilege of being raised by their own married parents.

While it is no secret that many Americans end up in a family environment different from what they want, the response of well-meaning voices to suggest single parenthood yields no differences in child outcomes, or that the only thing children need to thrive is love and money, apart from marriage, is deeply misguided.

Those raised in single-parent households, including this author, can still love and appreciate their own parents and families while recognizing that the data is clear: On average, marriage matters to our kids.

It’s for that reason the best pro-family approach for policymakers in Utah is to continue to figure out ways to reinforce the state’s outstanding record as the state where the married family is strongest. And one of the best ways to achieve that end is by promoting the success sequence. Utah’s youth deserve to know this proven pathway to a better life.

Brad Wilcox, a professor of sociology at the University of Virginia and director of the National Marriage Project, is the Future of Freedom Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies and a visiting scholar at the Sutherland Institute.

Editor's Note: This article appeared first in The Deseret News. It has been reprinted here with permission.