Highlights

- Since the late 1990s in particular, the increasing cost of raising children, high unemployment rates for the youth, and low wages for college graduates have resulted in the postponement of marriage and childbearing in Taiwan. Post This

- Despite the government’s recent pro-natal efforts, Taiwanese fertility is unlikely to recuperate in the near future. Post This

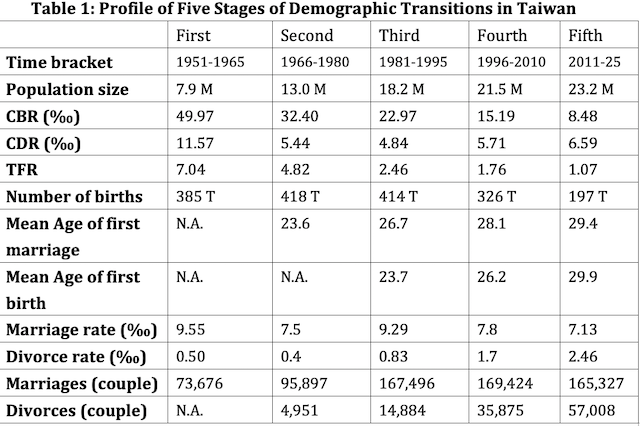

Taiwan has experienced rapidly declining fertility since 1950. The total fertility rate (TFR) was 7 in the early 1950s and fell to the replacement level of 2.1 in 1984. Surprisingly, the TFR dropped again quickly in the first decade of the new century and a new historic low emerged of 0.9 in 2010. Although there was a rebound in the next five years, the TFR dropped again (see Figure 1 below). In 2018, the TFR was 1 and only 182,000 babies were born.

Note: The birth numbers shown on the red line are during the year of the Tiger and Dragon. The TFRs

on the blue line are the beginning of each stage. Source: Dept. of Household Registration Affairs, Ministry of the Interior.

The theory of demographic transition (DT) was proposed by Warren Thompson for describing the decline of fertility and mortality from high to low levels. The driver of these changes, which primarily occurred after World War II, was industrialization, which resulted in the increase in the survival chances of children and their living costs to parents. The speed and time of the changes might differ among countries; however, this theory seemed inevitable and irreversible.

The second demographic transition (SDT) was coined by Lesthaghe and van deKaa more than 30 years ago for examining a new scenario of the population in recent decades. The SDT theory depicted the continuous declining of fertility to replacement level and the prevalence of some demographic features particularly occurring in the western world. First, the weakening of marriage resulting from high divorce rates and a rise in cohabitation. Second, a shift in family relations from king-child to king-couple. Third, a shift from preventive contraception to self-fulfilling contraception. Fourth, the uniform conjugal family starts giving away to more pluralistic forms of families.1

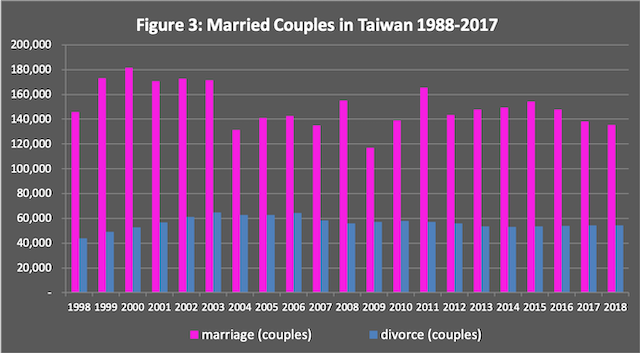

With these socio-economic and political factors in mind, I grouped Taiwanese demographic transitions into five stages for the period from 1951 to 2025. Each stage covers 15 years of the time frame (see Table 1 in the Appendix). I discuss the fourth and fifth stages in relative detail because of the demographic challenges happening in the new century.

1. Self-adjusted Childbearing Stage (1951-1965)

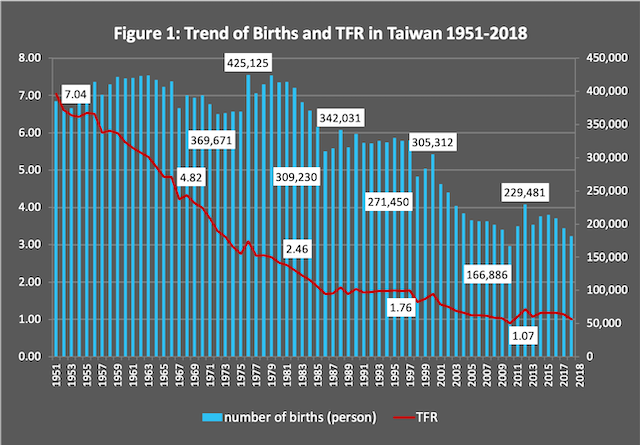

In 1951, the TFR in Taiwan hit the mark of seven persons and took a continuous dive, dropping to 4.5 in 1965. The average of 400,000 babies born annually during this stage were dubbed the “Taiwanese Baby Boomers.” The reason for more children in the 1950s mainly reflected the parents' childhood experiences of high mortality rates during the early decades of the 20th century. Improvements in sanitation and medicine and the concurrent diminishing of contagion diseases (i.e. malaria) resulted in the decline of infant mortality, in particular. Therefore, additional childbearing was not needed for the supplement of early deaths. Women began to reduce unnecessary births mainly by ending childbearing at ages 35 or above, as shown in Figure 2.

Source: Dept. of Household Registration Affairs, Ministry of the Interior.

This stage coincided with SD theory. The crude death rate (CDR) rapidly dropped from 11.6 per thousand to 5.5, while the crude birth (CBR) rate also declined from 50 per thousand to 33. The gap between CBRs and CDRs were still significant and resulted in high natural growth rates of more than 30 per thousand. The total population size thus increased from 7.9 million to 12.6 million during this stage.

2. Family Planning Stage (1966-1980)

Just a few years before 1969, when the Taiwanese government decided to stipulate family planning into policy guidelines, some contraception programs had already been carried out island-wise.2 "Two kids just right for a family" was the major slogan advocated by the government. The government also carried out economic plans toward industrialization and expanded compulsory education from six to nine years in 1968. The increasing chances of being able to obtain schooling and enter the labor market made late fertility more rational for a better life.

Facing a global oil crisis in 1974 and 1978, the government was valiant and bravely launched the big-ten constructions, which lasted for more than a decade. In addition, Taiwan had also experienced diplomatic defeats during this stage, such as withdrawing from the United Nations in 1971, and breaking off the relations with the UK and Japan the next year, followed by the United States in 1979. This stage was characterized as the most turbulent period for the government and the people of Taiwan.

As a result, the TFR dropped from 4.5 to 2.6 and the decline occurred in all childbearing ages. The population growth began to slow down; however, the total population still experienced a 5 million person increase during this stage.

3. Modernization Stage (1981-1995)

In Taiwan, economic growth took off in the late 1970s and persisted for around 20 years. The average economic growth rate was over 8% annually in the 1980s with the decline of income inequality—the so-called “Taiwanese Economic Miracle.” Accompanied by industrialization, urbanization resulted in the migration of youth from rural areas to cities, where they were likely to get jobs and to get married. Due to the rising cost of child rearing, a family of two working parents with one or two children was more welcome for new generations, especially in cities. With the prevalence of the nuclear family, the TFR continuously dropped to replacement level in 1984 and further fell to under replacement level during this time.

It is worthwhile to note that the government terminated martial law (initiated in 1949) in 1987. Freedom and autonomy on college campuses became one of the popular catchwords of that time. The government expanded higher education rapidly due to the growing economy, the upgrading labor market, and the rise of the college-aged population in the 1990s.

The college net enrollment rate was 20% in 1980, and it climbed to 50% in 2000. Thus, young people spent more time in school, which delayed getting married and having children. Besides, the government policy began to shift from a family-centered one to a government-centered one, and some important welfare acts were promulgated during that time. The ideas of gender equality and feminism also become prevalent on college campuses.

4. The Lowest-low Fertility Stage (1996-2010)

Not surprisingly, the TFR dropped to 1.47 in the tiger year of 1998, and it rebounded to 1.68 in the Millennium dragon year. In 2003, the TFR dropped to 1.24, which was below the threshold of "lowest-low fertility rate."3 In 2010, the TFR even dived to a historic low of 0.9 with less than 170,000 births.

According to SDT theory, the postponement of childbearing has emerged as a crucial determinant among developed countries.4 The reasons for such rapid delay of childbearing include ideational change, the rise of women’s education, and the increasing uncertainty during young adulthood, and the emergence of “latest-late” transition to adulthood.5

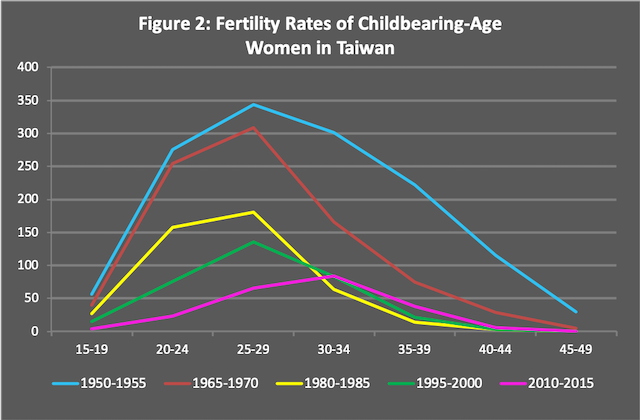

What happened in 2010 in Taiwan? In the second half of 2008, the bankruptcy of the Lehman Brothers engulfed the world in a global financial crisis and the depression lasted for a few years. Unfortunately, the Typhoon Morakot also lashed Taiwan in August 2009, which worsened the economic situation of the country. All these events resulted in fewer marriages in 2009 and fewer births in 2010. According to Chinese zodiac heritage, births also fell because people were unwilling to get married and have children in the year of the Tiger (see Figure 1 above and Figure 3 below).

Source: Dept. of Household Registration Affairs, Ministry of the Interior.

Modernization effects, as the SDT theory described, occurred in Taiwan during this stage. In addition, despite the declining college-aged population that began in 2000, the government still expanded higher education in the early twenty-first century. A large share of the youth enrolled in higher education and experienced rising unemployment due to the economic depression. The new generation (i.e. the Millennials) was not only spending more time on higher education but also learning progressive ideals such as individualism.

In this stage, the mean age at first marriage moderately increased among Taiwanese females by 1.3 years, from age 28.1 to 29.4, and the mean age at first birth significantly increased by 3.7 years, from age 26.2 to 29.9. Unlike countries in the West where nonmarital births were high, Taiwan, like Japan and Korea, had a low rate of nonmarital births (less than 4%), although it slightly increased in this stage.

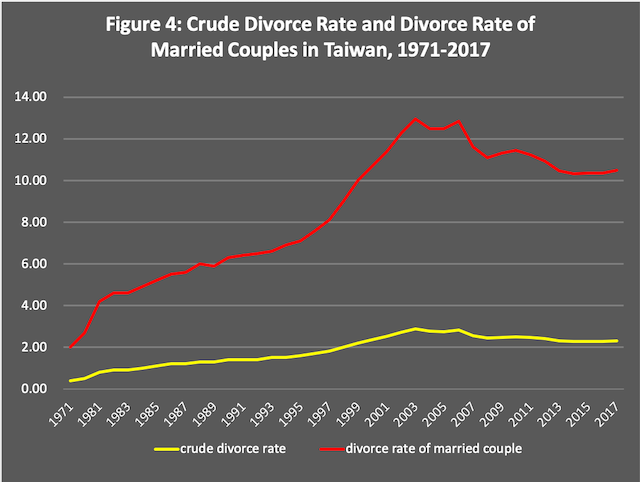

On the other hand, divorce rates dramatically increased, as Figure 4 shows. The crude divorce rate was below 2 per thousand in the third stage and it rose to 2.8 per thousand—a record high—in 2002, surpassing the average divorce rate in OECD countries, and it dropped to 2.1 in 2010.

Source: Dept. of Household Registration Affairs, Ministry of the Interior.

Thus, new groups emerged from these unstable marital relationships, such as the increasing number of single-parent families.

Despite being listed as one of the lowest fertility countries by the U.N. since 2004, the government hesitated to boost fertility mainly due to concerns about a high-density population (650 persons per square kilometer) in Taiwan. Even by the year 2010, some cabinet members continued to welcome our falling population size for the sake of limiting the land usage and energy consumption.

5. The Time-to-Change Stage (2011-2025)

Beginning in May 2008, when Kuo Min Tang(KMT) took power, the government launched some pro-natal measures. These measures included: a 6-month parental leave policy with 60% payment for both parents, a tax reduction for families rearing children ages 0 to 5, a nursing and childcare subsidy, sound daycare and babysitting systems, education privileges or subsidies, and low-interest housing loans or rent subsidies for new parents, and more—all enacted in or after the year 2010.

Between 2011 and 2015, the TFR in Taiwan rebounded to 1.2 and the number of births soared to 210,000, on average. Although Taiwan's TFR was still listed as one of the lowest in the world, the bounce back showed some important explications for Taiwan with respect to the long-term decline of fertility. The policy also emphasized the value of family and might result in the decline of divorce rates between 2011 and 2015.

As Figure 3 illustrates, the number of marriages rapidly dropped from 155,000 couples in 2008 to 117,000 couples in 2009, the year of Taiwan’s abysmal depression, which resulted in very low fertility in 2010. The government, therefore, encouraged young people to get married when the economic situation began to show signs of recovery, which successfully resulted in over 21,000 more marriages in 2010 than in 2009, plus an additional 26,000 marriages in 2011. Of special importance was the increase in marriages in both 2010 and 2011 that resulted in recuperating births in both 2011 and 2012. In sum, the recuperation of fertility during 2011-2015 could be attributed to the recovery from the economic depression and the implementation of pro-natal measures, as well as the influence of Chinese traditional culture (such as the dragon year in 2012).

To some extent, Taiwan completed the first demographic transition in the 1980s and soon fell into SDT in the 1990s. Unfortunately, the trend of declining fertility in Taiwan seems to have no end in sight in the near future. For instance, compared with females of the 1960 cohort and 1980 cohort, of the former 83% married and having 1.9 birth by age 30 but only 60% married and having 0.8 birth for the latter.

The SDT theory might not correctly apply to Taiwan in the new century; nevertheless, the lowest-low fertility was indeed associated with the rapid postponement of marriage and childbearing. Since the late 1990s in particular, the increasing cost of raising children, high unemployment rates for the youth, and low wages for college graduates have resulted in the postponement of marriage and childbearing in Taiwan. Finally, and maybe more importantly, the individualism and couple-focused thought and lifestyles have undercut the traditional family values that once emphasized conjugal-and-natal responsibilities. Despite the government’s recent efforts, Taiwanese fertility is unlikely to recuperate in the near future.

James C.T. Hsueh is a professor in the Department of Sociology at National Taiwan University.

1. Zaidi, Batool and S. Philip Morgan 2017. "The Second Demographic Transition Theory: A Review and Appraisal." Annual Review of Sociology43:473-492.

2. Chang, Ming-Cheng 2003. "Demographic Transition in Taiwan." Journal of Population and Social Security (Population), Supplement to Volume 1, 611-628.

3. Kohler, H.P., F.C. Billari and J.A. Ortega 2002. “The Emergence of Lowest-Low Fertility in Europe During the 1990s.” Population and Development Review28(4):641-680.

4. Billari, F.C. and H.P. Kohler 2004. “Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe.” Population Studies 58(2):161-176.

5. Billari, Francesco C. 2008, " Lowest-Low Fertility in Europe: Exploring the Causes and Finding Some Surprises." The Japanese Journal of Population6(1):2-18.

Appendix