Highlights

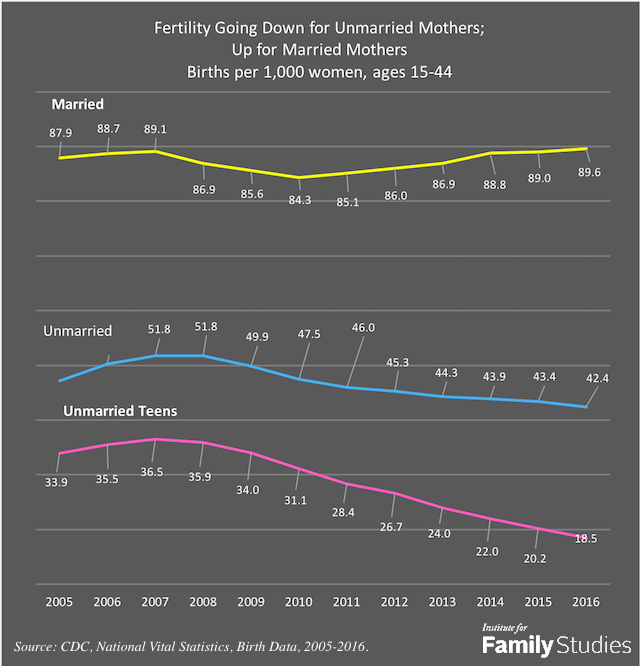

Americans are having fewer children than ever before, with the general fertility rate (meaning the number of births in a given year per 1,000 women aged 15-44) hitting a historic low in 2016. Less well reported is that fertility among married women has actually increased, with the recent overall declines driven entirely by unmarried women. Not since the late 1980s has the fertility rate among unmarried women, particularly teenagers, been so low.

While policy attempts to reverse fertility declines have received most of the attention, these marital status dynamics—declining births to unmarried teens in particular—should be kept in mind. Government policies that reverse progress on unmarried fertility, however well-intentioned, would be a mistake.

Demographers point to delays in childbearing and marriage as the cause for recent declines in U.S. fertility. As cultural messages against early, unplanned childbearing get stronger, delays in both marriage and childbearing are perhaps unsurprising.

This presents a policy paradox: On one hand, fewer children born to unmarried women, especially ill-prepared teenagers and young adults, is a welcome sign. Poverty is more common among these families, and research suggests that fewer children born into unmarried families (even when the biological parents cohabit), makes poverty reduction easier.

On the other hand, if the overall general fertility rate in the U.S. keeps declining, a number of challenges emerge. European and Asian countries concerned about economic growth and caring for an aging population have long warned about declining fertility. The idea that the same problem might exist in the US is looking increasingly likely. And if low fertility in the US slows economic growth, poverty becomes more likely.

American policymakers are starting to heed concerns, too. Republicans, who are typically against new government expenditures, have increasingly supported pro-natalist policies even though they can be expensive, often selling them as a way to help working families. Perhaps this stems from bipartisan fears that the aging of the population without replacement moves the nation closer to insolvency.

Late last year in The Atlantic, Emma Green wrote about the growing push from Republicans:

These are the seeds of a nascent pro-natalist movement, a revived push to organize American public policy around childbearing. While putatively pro-family or pro-child policymaking has a long history in the U.S., the latest push has a new face. It’s more Gen X than Baby Boom. It’s pro-working mom. And it upends typical left-right political valences: Measures like the Child Tax Credit find surprising bipartisan support in Congress. Over the last year or so, the window of possibility for pro-natalist policies has widened.

To navigate this paradox, lawmakers must be careful to design policies that balance pro-natalism with an emphasis on marriage and preventing teen pregnancies. The child tax credit is one example of a policy that promotes both marriage and having children, mainly because income eligibility is high enough that discouraging marriage is not much of a concern. But failing to address the marriage penalties in other government programs might actively work against family-formation efforts.

When thinking about pro-natalist policies, one area that is perhaps ripe for reform is reducing marriage penalties across government programs for low-income families. Many poverty scholars have recommended reducing marriage penalties in various safety net programs. Yet the extent to which government programs actually delay marriage and having children remains largely unknown. If these programs discourage marriage (or encourage unmarried childbearing) they should be reassessed in light of the positive relationship between child well-being and living with two married parents.

It’s not too hard to imagine a young couple finding marriage and childbearing economically challenging, preferring to wait or avoid them entirely. And any help from the government for low-income families disproportionately benefits those who are unmarried, mainly because when determining eligibility for assistance the income of both spouses is considered. When couples realize that the majority of low-income public support goes to unmarried parents, marriage might seem ultimately unattainable, unnecessary, or counterproductive.

Congress has the ability to change programs in ways that support fertility without hurting marriage, but that will require tough choices. A good first step is to further reduce the marriage penalty in the earned income tax credit by expanding income eligibility and increasing the credit for married couples. Future efforts should include making the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, child care, and housing assistance more generous for low-income families who are married, which is the opposite of what happens now.

Family-friendly workplace policies can also play a role. Married women have greater access to paid parental leave and childcare because they tend to be more educated and have higher incomes than their unmarried counterparts. Establishing a causal link is difficult, but it’s possible that this access has contributed to increasing fertility rates among married women, while lower-educated unmarried women have experienced the reverse. Enacting paid leave and childcare policies that reach low-income couples might help boost both marriage and fertility.

Finally, cultural norms and messaging are important. In 2015, the AEI-Brookings working group on poverty and opportunity recommended promoting“delayed and responsible childbearing” through cultural means as a way to reduce poverty, along with messaging that raising children jointly with the other parent leads to better child outcomes. Perhaps this message is getting through but to the detriment of overall fertility. Messaging around the values of marriage and marital childbearing might be needed to counteract declines in unmarried fertility.

Although no one policy will entirely reverse a deeply cultural phenomenon like declining fertility rates in the U.S., making marriage and marital childbearing easier deserves a serious look. Reducing penalties in safety net programs, making marriage more attractive and easier through family-friendly workplace policies, and paying close attention to public messaging around marriage and childbearing is a good place for policymakers to start.

Angela Rachidi is a research fellow in poverty studies at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where she studies poverty and the effects of federal safety net programs on low-income people in America.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.