Highlights

With the explosion of children born outside marriage or experiencing parental divorce, unprecedented numbers of children born today will spend time living with one parent and that parent’s sexual partner. (More than half will see their parents break up or divorce by the time they reach eighteen.)

As families move outside the confines of marriage, the law becomes deeply schizophrenic, sometimes treating relationships between adults and the children in their care as families and other times, as no more than legal strangers.

In times past, marriage supplied all the legal linkages needed for adults and children to be considered a family. The adults were related by marriage, and the children were connected to them by biology, adoption, or a presumption of legitimacy. To determine who was a legal family, the state looked no further than an adult’s marriage.

Not so easy today. For a child, is a parent’s new spouse a family member? What about a parent’s live-in partner? How about the parent's romantic interest, whether long-term or fleeting? The law classifies all these situations very differently, and it gives very different answers depending on the legal issue at hand.

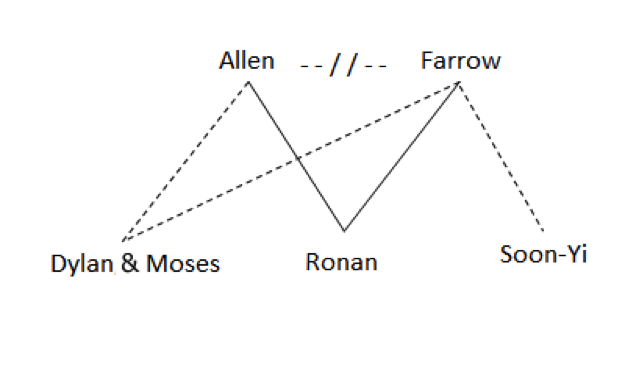

The perfect illustration? The “strangest entry on [the] love triangle list”—Woody Allen, Mia Farrow, and Soon-Yi Previn—again in the news after fresh allegations of child molestation by Dylan Farrow, Woody and Mia’s adopted child. A family diagram will help:

Solid lines show a relationship by biology; dotted lines, adoption.

Recall that in 1992, Woody and Mia ended a twelve-year relationship, during which they kept separate homes across Central Park (in addition to Mia’s other home in Connecticut) and never married. Woody and Mia adopted two children, Dylan and Moses, and had a third, Ronan, the old-fashioned way (although Mia intimated in a 2013 Vanity Fair interview that Ronan may be the child of her first husband, Frank Sinatra). Rounding out this “family” were six other children living with Mia, including her adopted daughter from another marriage, Soon-Yi Farrow Previn. Woody never adopted Soon-Yi or lived with her.

Soon after the couple split, Mia discovered nude pictures of Soon-Yi, then an adult, reportedly taken by Woody. Five years later, in 1997, Woody and Soon-Yi married. Last month, Dylan published graphic descriptions of “sexual assault” by Woody beginning when she was seven years old.

In this mish-mash, who counts as family?

First, the easy part. Dylan, as Woody’s adopted child, receives the protections accorded to family members under the law. If whatever happened injured or caused substantial risk of harm to her, violated “penal law” (as sexual abuse does), and was committed by her adoptive parent, Woody (a “family or household member”), then Dylan would be a “victim of domestic violence”—bringing to bear important remedies.1 When something goes terribly wrong in a family, New York law authorizes protective orders and emergency shelter, counseling and other services.2 Those who suffer sexual abuse at the hands of a non-family member may not have access to those resources, and the protective order would come from a different court.

If Mia had experienced violence at Woody’s hands (no one alleges that she did), she would count as a domestic violence victim, too—both because she and Woody have three children in common3 and, independently, because they had an “intimate relationship,” which can occur “regardless of whether [they] lived together.”4

Soon-Yi’s relationship to Woody poses a tougher question. Again, no abuse has been alleged, but Soon-Yi would qualify for the statute’s protection only by virtue of an “intimate relationship” with Woody, which can be found in the absence of sexual relations or living together.5 But there is no assurance that a judge would make that call.

So some kids definitely get domestic violence protection; others may not.

The law should speak with a single voice: a child is an adult’s family member for every purpose, or none at all.

The law treats the same kids differently in other contexts. Consider New York’s incest statutes. New York law makes sexual acts between an “ancestor” and “descendant” a felony6 and bars incestuous marriages between relatives, whether related by “the whole or the half blood.”7 So under New York law, Woody could not marry Ronan because of consanguinity—assuming Woody is Ronan’s father. But adopted children, like Dylan, and stepchildren appear nowhere in the incest prohibition. Some other states have construed incest statutes to give adopted and stepchildren the same protection under law as biological ones. But no state would bar a marriage between Woody and the child of Woody’s former romantic interest, Soon-Yi, whose mother he never married and with whom he never lived—although many today would see Soon-Yi as Woody’s “social child.” Should social children receive the same protections as other children?

True, incest restrictions are designed to prevent hereditary diseases in the children of closely related individuals. But just as compelling, incest restrictions prevent predatory behavior by adults with unique power over any child—biological, adoptive, or social—who sees the adult as a parent, by taking sexuality and sexual relationships off the table. In essence, by bracketing sexuality, children can develop close relationships with parental figures without questioning the meaning of a hug or other physical contact.

As the American family continues to morph, the law should speak with a single voice: a child is an adult’s family member for every purpose, from sexual abuse and incest to protective orders in cases of family violence, or none at all. If the need to protect a child in the adult’s care is so compelling that the domestic violence statutes apply, then incest restrictions and other legal protections need to keep pace.

Robin Fretwell Wilson is the Roger and Stephany Joslin Professor of Law at the University of Illinois, where she directs the Family Law and Policy Program.

1 N.Y. Soc. Serv. Law, Article 6-A: Domestic Violence Prevention Act available here; See also Part 5 of the Article 1 of the Family Court Act; N.Y. Fam. Ct. Act § 812 (defining family the same way for the purposes of family court jurisdiction).

2 N.Y. Soc. Serv. Law, Article 6-A: Domestic Violence Prevention Act available here.

3 N.Y. Soc. Serv. Law § 459-a(2)(d).

4 Id. at (2)(f).

5 Id. Failing that, a catch-all protects “individuals deemed to be a victim of domestic violence as defined by the office of children and family services in regulation.” N.Y. Soc. Serv. Law § 459-a(2)(g).