Highlights

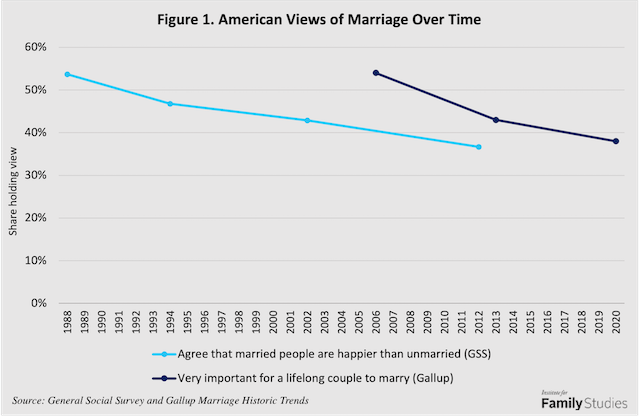

Does getting married make you happier? The proverbial wisdom of many societies has been that marriage was an essential part of a good, happy life. But, in modern societies, this is more debated. Gallup polls and the General Social Survey (GSS) alike show that fewer Americans believe marriage is key to happiness, or that it’s important for lifelong romantic partners to marry, as shown below in Figure 1.

What makes these trends especially galling is that they are in some cases empirically wrong. Indeed, married people are happier than unmarried people: across nearly five decades of surveys, data from the GSS shows that 36% of people who have ever been married (including divorced, separated, and widowed people) say they are “very happy” while just 11% are “not too happy,” compared to 22% and 15% for people who have never married. Despite changing public views, the truth is married people really are happier.

But there’s a more charitable way to interpret the views of the growing number of people who are skeptical of the benefits of marriage. Maybe married people are happier, but it’s not because of marriage. Indeed, maybe happy people are just more likely to get married! There is some strong empirical evidence for this view. One very influential paper showed that in several decades of German longitudinal data, self-reported happiness began to rise just before getting married, peaked in the year of marriage, then declined within a year of marriage, with larger effects for women than men. Other papers have built on this, such as a prominent recent paper which compared cohabiting and married people, and found that higher happiness in marriage was due to other contextual factors, not marriage itself. These findings and others like them have led many people to discount the happiness benefits of marriage as just a product of bias and selection: happy people get married; marriage itself doesn’t make people happy. This research, however, turns out to be even more pessimistic than it sounds: the same methods that suggest marriage doesn’t impact happiness also tend to suggest that many other life experiences like unemployment and widowhood also don’t impact happiness much. In other words, this research implies that the reason poor, unemployed, lonely, or disabled people are less happy isn’t that bad things happened to them: they’d be unhappy no matter what.

Other recent research, however, has challenged this pessimistic view. Data from a large British panel survey show that marriage increased long-run happiness, suggesting that “selection” isn’t the whole story. Perhaps marriage doesn’t make Germans happy, but it does seem to make the English happy. Likewise, a paper using panel data from Taiwan has found somewhat more durable positive effects of marriage (though this there was a lot of variety in happiness trajectories, and Christians might get more happiness from marriage than other people).

However, research on happiness is bedeviled by a problem: there are only a few datasets which track people over time and measure their happiness. Many longitudinal surveys (like the National Longitudinal Surveys of Youth in the United States) don’t ask about happiness at all. Indeed, the United States has proved to be a major blind spot in happiness literature, as there are few longitudinal surveys in America that ask about happiness.

Luckily, since 2006, the GSS has included a longitudinal follow-up component. Because the GSS asks about happiness and marital status, this data can be used to see how happiness changes around key family events, in particular marriage, divorce, and widowhood. With several rotating panels of respondents totaling about 9,600 two-year-change observations, the GSS provides a fairly small sample size with a fairly short follow-up period, so can’t provide an exhaustive test of the effect of marriage on happiness. Within that overall sample, there are just a few hundred changes of marital status. But some respondents, about 4,300, were followed for four years rather than two, making longer-term analysis possible.

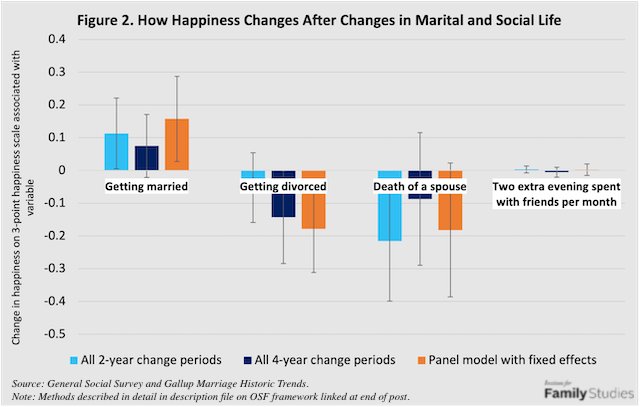

Despite the small sample size and short time window, the GSS is a longstanding survey with high data quality, and as one of the few U.S. surveys with any longitudinal happiness data, it provides an invaluable window into whether married might boost happiness in the U.S. as it does in Taiwan and the United Kingdom and in the short run in Germany. Figure 2 shows the estimated effect on happiness (on a scale ranging from 1 to 3) of four changes in family and social life. It shows results from three models: first, a model looking at all two-year changes in happiness individually, so showing short-run changes in happiness after marriage; second, a model looking at all four-year changes in happiness individually, so showing slightly longer-run changes in happiness after marriage; and third, a more technical model using “fixed effects” which estimates effects of marital status on happiness within individuals across multiple time periods. All models also show the effect of any person spending about 2 more evenings a month hanging out with their friends, estimated among the same respondents. Because the frequency of spending time with friends changes a lot more than marital status, results for social time with friends are estimated more precisely.

Effects for major family changes are all estimated imprecisely, with wide error ranges. Nonetheless, some important conclusions can be reached. Getting married significantly increases happiness within a 2-year time frame, and while the effects at the 4-year window are somewhat diminished and no longer statistically significant given the smaller follow-up sample, the estimated coefficient seems broadly similar. The overall effect, an increase of around 0.05 to 0.1 points of happiness on a three-point scale, may seem small, but the average happiness change was just 0.02, and a change of 0.1 points is similar to the effect of a decade of aging. Happiness on a 3-point scale just doesn’t change all that much. The panel model finds larger and more significant effects. In other words, “newlywed” happiness boosts are very clear, but even in the longer run, it seems like being married is associated with a person being happier than before marriage.

Moreover, there are other reasons to think being married might boost happiness. The fact that all models indicate negative effects of divorce and spousal death, sometimes quite significantly so, is striking. If exiting marriage makes people less happy, it stands to reason that being in the marriage was a component of happiness.

While there is some attenuation of effect over time, the central estimate of marriage’s impact on happiness at four years is much larger than was found in, for example, the German data described above. The Taiwanese example found significant happiness effects around 2 years, but noisier effects beyond 3 years, similar to what I find in the GSS, suggesting that marriage in the U.S. has effects more similar to the positive cases of Taiwan and the UK.

One other change should be mentioned: friendship. One reason many people today believe marriage is not vital for happiness is the rise of “chosen family” and the idea that a close circle of friends can substitute for more traditional kinds of relationships. The GSS provides no support for this idea. When people reported increased frequency of “social evenings spent with friends,” even large increases, there was essentially no associated change in happiness. This doesn’t mean that friendship is irrelevant for happiness, of course, especially since “social evenings spent with friends” is a very crude measure of true friendship. But this does suggest that, at the high level, filling your life with game nights and book clubs and outings with friends is unlikely to yield as much happiness as marriage. There simply is no substitute for marriage.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Note: All data and code used for this analysis are available at the associated OSF page. For the two-year sample, GSS respondents observed at the initial, +2, and +4 intervals are treated separately at the +2 and +4 intervals. GSS variables “happy,” “socfrend,” “marital,” “sex,” “year,” and “age” are used. “Age” is used as a discrete control variable for the age at the initial observation period. The dependent variable is the change in the variable “happy,” ranging from +2 to -2. Change in marital status is identified from changed responses to “marital” at the initial and follow-up periods. For each persona and period, the appropriate 1-2 or 1-2-3 wave weights are used. “Socfrend” at initial and follow-up periods is converted into an index estimating the number of social evenings implied per year by the categorical response given, with changes between initial and follow-up periods identifying the change in estimated number of evenings spent with friends per year.