Highlights

Imagine you’re a divorce lawyer—and indeed you may be. Now imagine that every time one of your clients comes to see you to finalize their divorce papers, you routinely ask them a couple of questions about the state of their marriage. Six months to a year before the divorce, you ask, how happy were you with your relationship? And how often did you quarrel? I’m guessing that you’d expect most of your clients to say either that they were “unhappy,” or that they quarreled “a lot,” or both.

The reality may surprise you. It certainly surprised me.

Together with Professor Spencer James from Brigham Young University, Marriage Foundation analyzed data on 22,000 UK men and women who were living as a couple, either married or unmarried. Each person was interviewed at least twice over a period of four years for Britain’s biggest ongoing household survey, Understanding Society. Some of the married people subsequently divorced. Some of the unmarried people also split up. But in the year before they separated, they answered exactly the questions I posed above. The difference was that this was what they felt at the time. So there is no danger of rewriting of history in the aftermath of a divorce or separation.

Our findings are published in a new study for Marriage Foundation and reported in The Sunday Times.

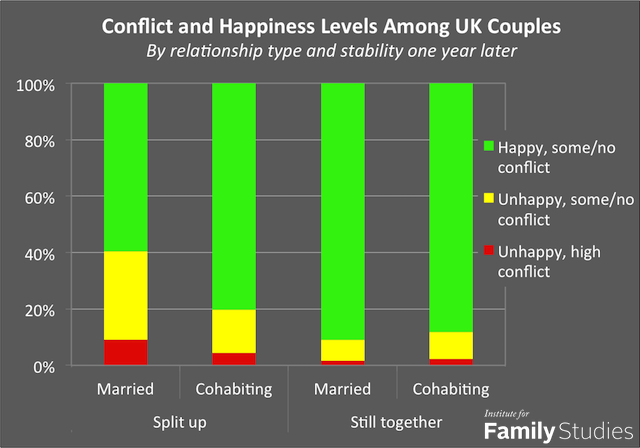

Here’s what we found. Couples who were headed for divorce one year later fell into one of three categories while they were still married.

- High-conflict couples: 9 percent of UK divorces were preceded by both unhappiness and a lot of quarreling.

- Unhappy couples: 31 percent were preceded by unhappiness but only some or no quarreling.

- Low-conflict couples: 60 percent were preceded by both happiness and only some or no quarreling.

It’s easy to see why high-conflict couples divorce. Their unhappiness comes out in frequent quarrels. The atmosphere at home is miserable for both the couples themselves and any children they have. Divorce comes as a huge relief to everyone. The big surprise, however, is how few divorces fall into this category: just one in ten.

It’s also easy to understand the unhappy couples. They don’t argue much, if at all, perhaps because they’ve already given up and mentally left anyway. But they’ve stopped communicating and probably give each other the silent treatment. The atmosphere at home is frosty. For the unhappy partners, at least, if not their kids, divorce also comes as a relief. That’s one in three divorces.

But what about the low-conflict couples? Astonishingly, they make up the majority of all those who divorce. Among unmarried couples who split up, it’s even higher at 80 percent. So most people who are going to split up, whether they are married or not, are neither unhappy with their relationship nor quarreling especially often. In fact, they looked little different from the vast majority of couples who stay together, mostly happy and mostly not quarreling too much.

So why on earth do so many apparently happy couples split up? Remember that these are not people who might be happy with life but just not with their relationship. They are specifically asked about their relationship. If they were unhappy, secretly or not, there is a box marked unhappy. They could tick that if they wanted, but they don’t. They tick one of the happy boxes.

For some of these spouses, divorce will be a genuine bolt from the blue. One person is deeply unhappy and the other hasn’t a clue. That happened to me many years ago (I was the clueless one), although mercifully we managed to turn things around and make a whole new and better marriage. Or maybe one person is having an affair and the other doesn’t see it coming. The ignorance of one spouse in an asymmetric marriage can certainly explain part of the 60 percent who are low-conflict divorces.

But this doesn’t feel anywhere like an adequate explanation. For the rest, I can only defer to my coauthor Spencer James, who found an almost identical situation among U.S. couples headed for divorce. Just 15 percent of U.S. couples headed for divorce could be described as high-conflict, while 66 percent were low-conflict. His explanations for the happy divorcees were down to a decline in the idea of marriage as a permanent lifetime commitment, changing norms about sticking with a difficult relationship, and a consumer attitude that now extends to marriage.

Whatever the reasons, it’s clear that a majority of divorces—and the vast majority of splits among unmarried couples—come out of the blue. If this is how adults see it, the effect will be magnified for any children involved.

The bad news is that most families who split were neither fighting nor unhappy in the months preceding the break-up. I’ve often highlighted that it’s the low-conflict divorces that are most damaging to children, because they don’t see it coming. It comes out of the blue.

The good news is that this gives me hope that family breakdown is way higher than it need be. If most couples who are headed for divorce look near enough identical to couples who stay together, then this strongly suggests that a great deal of family breakdown is a lot more preventable than previously thought.

If norms and social attitudes can change towards divorce, then they can also change towards marriage.

Harry Benson is Research Director of the UK-based Marriage Foundation. An earlier version of this post appeared on the Marriage Foundation blog.