Highlights

- A new paper suggests that religious connection is an important limiter of risk for a death of “despair.” Post This

- The decline of social capital writ large has almost certainly made the situation of the white working class worse, including their risk of death. Post This

- Frequency of church attendance (in the General Social Survey) is correlated with death-of-despair rates at the state level. Post This

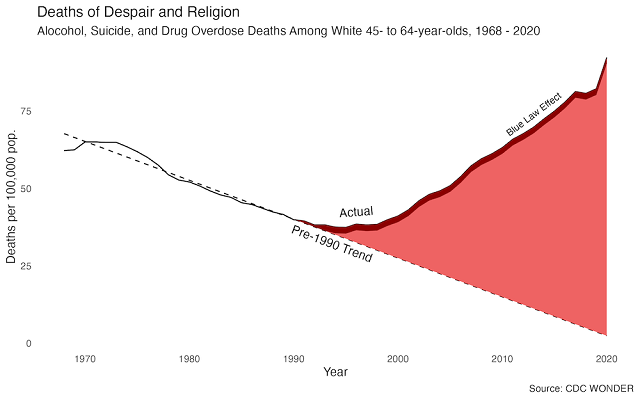

The precipitous rise in “deaths of despair”—the collective term of-late assigned to suicide, alcohol, and drug overdose deaths—among middle-aged, poorly educated whites, has been covered at length since Anne Case and Angus Deaton first drew attention to it in 2015. Commentators, drawn in part by evocative terminology, have linked this increase to a host of social and spiritual ills.

I’ve been skeptical of both Case and Deaton’s work and the more general idea that “deaths of despair” names a single underlying crisis, rather than several discrete increases in cause of death categories. That said, much analysis of the social determinants of these crises remains undone. We know that pharma over-prescription seeded the drug portion of the crisis, and that worsening economic conditions in the heartland exacerbated it. But how do changing social conditions shape it?

A recent working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research offers some insight into this question, and particularly into the role that declining religious affiliation has played in the increase. While its results are modest, it suggests that religious connection (and social capital more generally) is an important limiter of risk for a death of “despair.”

Declining religious affiliation should not be news to IFS readers. Relative to the early 1990s, Americans are much more likely to identify as religious unaffiliated—roughly 30% of the population as of the most recent data. The NBER paper begins with the observation that this decline began around the same time as the increase in suicide, drug, and alcohol mortality among middle-aged, less-educated whites, also a group that has grown significantly less likely to be affiliated with a particular religion. Observationally, the paper shows, frequency of church attendance (in the General Social Survey) is correlated with death-of-despair rates at the state level. So maybe there’s a connection!

But how to know if that connection is causal? That is to say, how can we determine whether a reduction in religious involvement caused an increase in deaths of despair, rather than a third, omitted variable causing both, or even the increase in deaths of despair causing the decrease in religious involvement? To address this question, the new paper exploits a well-established instrument: the repeal of blue laws, which prohibit commercial activity on Sundays. Repeal, in turn, increases the opportunity cost of attending church, reducing religious involvement at the margins.

The paper exploits the staggered roll-out of blue law repeals to construct a standard difference-in-difference analysis—essentially, comparing church attendance and death rates in places with and without blue laws, before and after the repeal went into effect. It replicates the conventional finding that blue law repeals reduce church attendance, cutting the share who go weekly by 5 to 10 percentage points. Further, blue law repeal increases the rate of deaths of despair by two per 100,000 people.

The obvious question, of course, is “how big is two deaths per 100,000?” By way of comparison, the paper’s authors note that it’s equivalent to a 4% increase over the average mortality in that age group, 51 per 100,000 in their data. But, they suggest, this is a particularly large effect in the pre-1996 period, when white middle-aged deaths were deviating from their pre-1990 trend by about 5 per 100,000.

Still, it’s worth putting their claim in context, as I do in the chart above. The dashed line represents the (linear) trend in pre-1990 data; the solid line is the actual death rate. My numbers are slightly different from the paper’s (I think because of slightly different data sets used), but the trend is the same. Light red shading captures the difference between the two, while dark red is what 2 per 100,000 looks like. What should be clear is that the religion effect is not that big in the aggregate—the increasing availability of synthetic opioids like fentanyl, in particular, explains a much larger share of the deviation from trend.

There’s one other caveat to the paper’s finding. Measuring “religiosity” is challenging: Does it mean religious belief? Religious practice? Involvement in a religious community? The measures that the authors use—frequency of attending a religious service and self-identified strength of religious “affiliation”—both measure social connection at least as much as they measure, for example, strength of religious belief. The authors acknowledge this, writing, “the mechanism at work in our results potentially pertains to attendance and participation in organized religion, rather than personal spiritual habits.”

Certainly, religious attendance is linked to better outcomes across a variety of measures. But its use as the paper’s main metric suggests the authors may simply be measuring not so much the effect of religion per se as the effect of access to social capital via church more generally. If personal connections moderate risk of death from alcohol, drugs, or suicide, then the form they take—church, work, the much-mourned bowling league—may be less important than their existence at all.

All of this is not to say, of course, that religious engagement does not necessarily play a role in the rise of these deaths. It probably does, like many other social factors. But that role is probably smaller than increases in the supply-side availability of drugs—or of means of suicide, for that matter—and similar to non-religious engagement. The decline of social capital writ large has almost certainly made the situation of the white working class worse, including their risk of death.

Charles Fain Lehman is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a Contributing Editor of City Journal.