Highlights

- “I’m all about me / so I rock that free BC,” goes a song for Delaware's pregnancy prevention ad campaign, “I bought myself roses / don’t need no snotty noses.” Post This

- The glossy tone of Delaware's ad campaign frames birth control as an expansive way of life, rather than a response to a narrowing of a woman’s options. Post This

- Behind the PSAs, the advisories for doctors are more candid about how LARCs fit into a culture that disempowers women. Post This

Bright lipstick, short skirts, fresh manicures. The singers in the music video for Delaware’s public service campaign advertising free contraceptives are polished and bright. The ad, which was a finalist for a Shorty Social Good award, was a project of DelCAN (Delaware Contraceptive Access Now). It directed viewers to a site where they could find clinics offering free, same-day appointments for contraceptive services in their neighborhoods.

The DelCAN program aimed to remove barriers for women seeking contraception, with a particular emphasis on providing long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs). The specially commissioned song put its emphasis on the way that a child could be a barrier to achieving one’s best life. Instead of having a baby, the song exhorted listeners to “be your own baby,” indulging in the kind of self-care and attention that would be impossible if someone else depended on you. “I’m all about me / so I rock that free BC,” one singer declares, while another sings, “I bought myself roses / don’t need no snotty noses.”

The song, intended by DelCAN to be “fun” and “empowering” for women ages 18-29, is out of step with most women who worry about unintended pregnancy and may seek abortions. The majority of women who seek abortions are already raising children, and about one-third of these women have two or more. Three-quarters of women who seek abortions say they are doing so because of financial instability. They are not keeping their options open and treating themselves; they are struggling to stay afloat.

The glossy tone of the ad camouflages this reality, framing birth control as an expansive way of life, rather than a response to a narrowing of a woman’s options. But behind the PSAs, the advisories for doctors are more candid about how LARCs fit into a culture that disempowers women.

Part of the case for LARCs, as explained by the Maryland Health Department, is that vulnerable women have only limited access to health care. Pregnancy and the immediate post-partum period might be the only time that vulnerable women can afford to see a doctor, since their pregnancy makes them eligible for Medicaid. The coverage lasts only two months post-partum, so the window for follow-up care is narrow. A woman who expresses a wish for a LARC at her six-week follow up may have only two weeks to receive it before her coverage lapses. Significant proportions of mothers do not make it to their six-week visit at all.

Thus, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommendation is to take advantage of the moment when “the woman and clinician are in the same place at the same time.” The ideal, according to ACOG, is to place the IUD “within 10 minutes of placental delivery in vaginal and cesarean births.” In some hospitals, that may mean the IUD preventing future births is placed before the present baby has been handed to his or her mother. The ACOG notes that IUD placement immediately post-partum has a higher failure rate (where the IUD is expelled) than placement later after birth. But they estimate that a poorer success rate is better than a purely hypothetical higher success rate. If a later appointment is impossible, then the success rate is nil.

The ACOG covers some possible counterindications and topics for discussion with women considering post-partum IUDs or implants. But they do not suggest doctors ask the question: “Do you have a plan for obtaining care to remove your IUD or implant when you are ready?”

A woman who relies on barrier methods for contraception can immediately return to trying to conceive—her fertility has always been intact; she and her partner simply skip applying the condom. A woman who uses the Pill can discontinue contraception on her own, though it may take three months or longer for her fertility to return.

But a woman who relies on an IUD depends on a doctor to be able to have children again. If IUDs are specifically recommended to women who have difficulty accessing medical care, these will also be the women who face the most obstacles to being able to conceive the children they want.

A woman who relies on an IUD depends on a doctor to be able to have children again.

Over a six-month period immediately following IUD insertion, seven to 15% of women surveyed in a study tracking patients in four states considered discontinuing their IUD use. Of the 45 women in the study who considered getting their IUDs removed but did not ultimately desist, 14 women said they were unable to get their IUD removed because they could not get an appointment or because their doctor actively discouraged them when they did come into the clinic.

A qualitative study interviewed family medicine practitioners in the Bronx about their reactions to patients who sought early removal of their IUDs. Many of the doctors interviewed said they tried to steer patients to IUDs, which are more effective at preventing pregnancy than oral contraceptives or barrier methods. The researchers found that the doctors were often reluctant to accede to patient requests. “It’s a negotiation,” said one doctor, who urges patients to try to stick it out a few more months.

Some doctors were dismissive of patient concerns about bleeding and discomfort. One doctor told the researchers, “I think [the symptoms are] more annoying than anything else. I don't think it's because they're worried they're bleeding out, or they're worried that something's not working.” Some providers felt a sense of personal failure if they couldn’t convince women to stick with the method that the doctor felt best suited their reproductive plans.

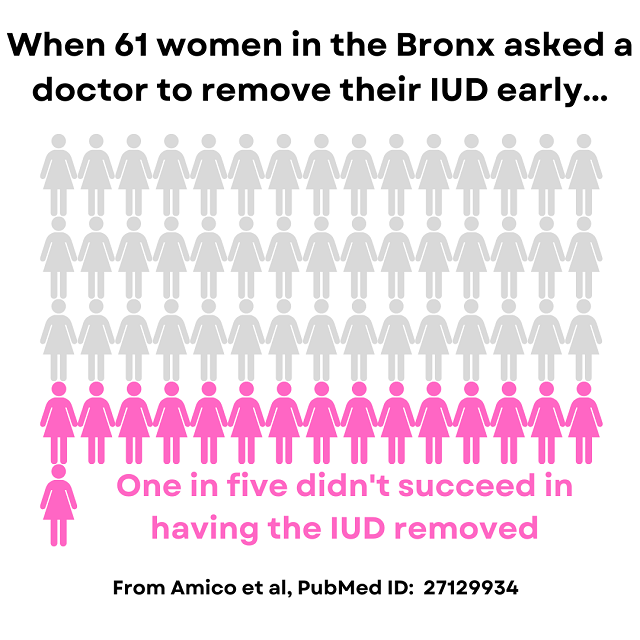

On the other side of the experience, a qualitative study of 61 women who sought early IUD removal in the Bronx in 2013-14 found that many of the women were told by their doctors to stick with the IUD. Doctors told their patients that their symptoms (pain, bleeding) were within the range of normal. That news was reassuring to some patients in the study, who worried that their experiences meant that something was wrong, but for others, it seemed like the doctor was more committed to their IUD than to them. One woman told the researchers, “You know, I was hoping that she was gonna side with me rather than the foreign object in my body.”

Other women felt that their doctors dismissed their symptoms or tried to blame them on the women, rather than the IUD. One woman made five successive appointments with different providers, but every doctor she saw would not remove her IUD.

To ameliorate these concerns, ANSIRH carried out an unusual study to discover whether it was possible for women to remove their own IUDs. Best practices are for women to have an IUD removed in a clinical setting. But just as ACOG recommends the less reliable IUD placement immediately post-partum, ANSIRH’s researchers wanted to consider whether a less-than-ideal IUD removal would represent a better option for women who couldn’t obtain help from a doctor.

Only a fifth of women who attempted to remove their IUDs were successful. But simply making the attempt and knowing it might be possible made women more likely to recommend an IUD to a peer. (The major determinant of success was the length of the removal threads.) Women were much more likely to request early removal of their IUD due to problems with bleeding (41%) and pain (36%) than because they were trying to become pregnant (22%).

Notably, 13% of the women who were interested in attempting to remove their own IUD said that one of their reasons was that “I thought it would hurt less than if a doctor/nurse did it.” Six percent said simply, “I did not want the doctor or nurse to do it.” It may seem strange to expect that a medical procedure would be less painful when done by an amateur at home rather than in a clinical setting by professionals, but these women’s expectations may have been shaped by their experiences in getting the IUD originally. Ignoring women’s pain is woven into the IUD experience, starting with the placement of the device.

For about one-sixth of women who have never given birth, having an IUD placed causes profound, agonizing pain. Some women describe it as worse than breaking a bone, or simply the most painful experience of their lives to date. Pain management offered is minimal (often the suggestion is to take an Advil prior to the procedure).

A meta-analysis of different pain management techniques did not identify a single, clear best practice, but some doctors are changing their practice to take a more aggressive and proactive approach to pain management, as the result of listening to their patients. Women may come up with their own solutions—at one workplace, a colleague of mine offered to share prescription medication with another coworker who was planning to get an IUD. Both expected the doctor would not offer adequate medication for the procedure. Increasing a woman’s access to medicine is only a partial victory if the doctor she sees has only a narrow view of her needs and her health.

The DelCAN project was carried out in partnership with Upstream, an organization that aims to reduce barriers to contraception by looking at every point in the medical process that might deter a patient or provider. The “Be Your Own Baby” campaign was intended to get women in the door, and it succeeded. DelCAN estimates that visits to Title X clinics rose by as much as 20% due to the ads. But Upstream knows that making an appointment is only part of the issue. They tried to identify and ameliorate speedbumps in the clinical setting like an office not knowing how to code a procedure correctly, a practitioner being reluctant to recommend options (like an IUD) that he can’t personally place, etc. The holistic approach appears to get results—in Delaware, the rate of unplanned pregnancies and the rate of abortions fell in tandem.

Upstream acknowledges the history of reproductive coercion and forced sterilization for vulnerable women in America. Some states have apologized for their eugenic programs, though few have paid reparations to their victims. Despite Upstream’s stated commitment to reproductive justice, it can still feel like they’re only offering the path to one choice. In a video featured on their results page, one doctor talks about her clinic’s shift in how they counselled patients. All patients are asked, “Do you plan a pregnancy in the upcoming year?” and if a woman says no, she is asked “What is your birth control method, and are you comfortable with it?”

The question presumes the only good pregnancy is a planned one, but many young women have more ambiguous feelings. In a study of women ages 18-24 in San Francisco, women reported both wanting to avoid pregnancy and that they weren’t using reliable contraception methods. They understood the risk and saw a possible pregnancy as somewhere between planned and unplanned. They didn’t feel ready to affirmatively try to conceive, but they felt comfortable leaving the door open to a child. After all, as the researchers put it, “they might never realistically reach a point where planning [pregnancy] would be possible.”

The doctor on Upstream’s site describes encountering a woman with these in-between feelings. When she says she feels open to whatever happens, the doctor describes, proudly leading her through Socratic questions about her future plans until the patient opts for birth control. Like the doctors who are reluctant to remove IUDs, she is clearly motivated by concern for the patient’s well-being, but her questions are asked without regard for a patient who might want to make the “imprudent” choice because structural factors seem to place the “prudent” one out of reach.

The DelCAN program succeeded at connecting women with IUDs and other forms of contraceptives because it recognized how many small factors might stand in a patient’s way. But the women of Delaware and elsewhere are still waiting for a program that would take the same comprehensive approach to the barriers that prevent women from having their own baby not being their own baby.

Leah Libresco Sargeant is the author of Building the Benedict Option and runs Other Feminisms, a substack community.

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.