Highlights

- In 2016, the share of babies born to unmarried moms fell below 40%, the first time it has been that low since 2007. Post This

- Virtually the entire decline in unmarried births can be explained, compositionally, by Americans becoming more educated, not by people of a given educational class having less unmarried motherhood. Post This

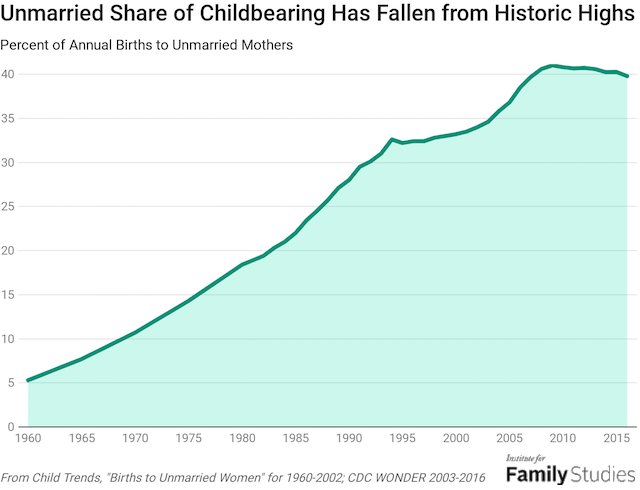

The share of children born to unmarried moms rose steadily from just 5% in 1960 to about 41% in the late 2000s: then it stopped rising and even declined. While a recent report from Child Trends highlights how high current levels are versus 1990, we are actually approaching a decade of falling births to unmarried moms. Of course, as I’ve argued before, these changes in marital status and childbearing are also driving the fertility rate lower for the whole country. Today, births to unmarried moms have declined enough that they are back below 40% of all births.

In 2016, the share of babies born to unmarried moms fell below 40%, the first time it has been that low since 2007. This is a large social change. Social and family policy in the post-war period incorporated a set of assumptions about what problems would be facing society in the future, particularly rising single-parenthood. The latter half of the twentieth century saw many single-parent-oriented benefits (like the EITC, which is more generous for single parents), aimed at addressing or alleviating the social and economic ills of fragmented families and kids with just one parent.

Today, while progress is slow, that problem is receding. A rising share of kids are born into two-parent homes. This is important for the child, as having two parents in the home is good for child outcomes, but also for adult parents, as being able to share childrearing and work reduces the economic and personal burdens of parenting.

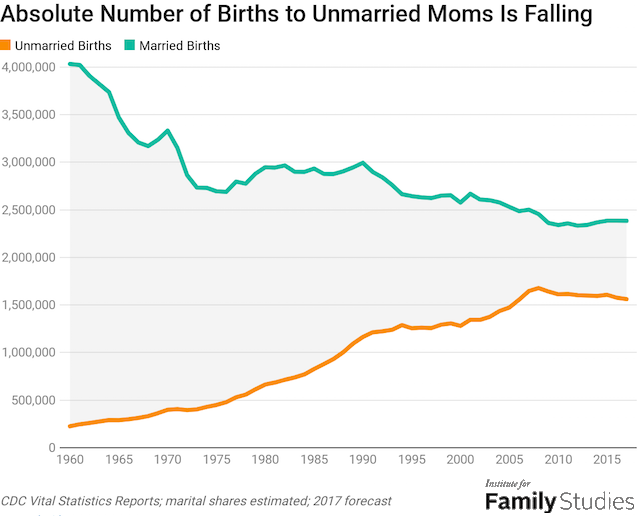

Crucially, this isn’t just about the share of births to unmarried moms. The absolute number of such births is falling.

Since the recession, unmarried births have fallen, while births within wedlock have risen slightly. If the share of children born to unmarried moms were falling simply because of more married births—but unmarried births were still rising—then it wouldn’t be quite correct to say that unmarried childbearing is on the outs. But with absolute numbers falling, it seems clear that we are genuinely enjoying a period where unmarried parenting is in decline.

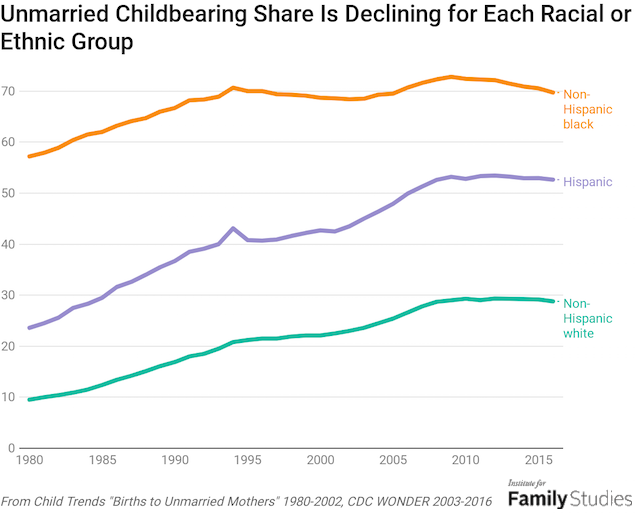

Crucially, this holds up across racial and ethnic groups.

African American women have seen the largest declines in the rate of unmarried childbearing since 2009; indeed, going back to the mid-1990s, unmarried motherhood basically has not risen among African Americans, while it has risen sharply for non-Hispanic whites and for Hispanics. But for both of those groups, we’ve also seen declines in the share of births to unmarried moms. Early evidence suggests these declines probably continue into 2017 as well.

In other words, the decline in unmarried motherhood is broad-based, and occurring across racial groups.

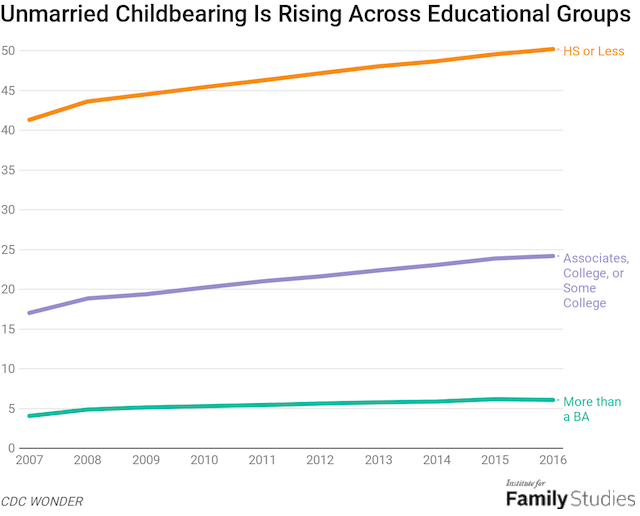

But the story across socioeconomic classes is quite different. We can assess changes in unmarried childbearing by educational attainment using CDC data since 2007.

Strangely, unmarried childbearing is actually rising within each educational group! This phenomenon, where the aggregate trend of falling single motherhood masks each subgroup having an opposite trend, is a mathematical curiosity called Simpson’s Paradox. And to be clear, this trend is even more true, if we control for the life-cycle-biased nature of educational estimates and restrict the sample for analysis to women over 25 or over 30, so women who have completed their educational course.

In other words, virtually the entire decline in unmarried births can be explained, compositionally, by Americans becoming more educated, not by people of a given educational class having less unmarried motherhood. Whenever the march of educational progress slows down, aggregate unmarried childbirth rates could start rising again.

The society-wide move away from a married two-parent family norm is continuing: for each educational group, more kids are born outside of marriage. It’s only the rapid increase in educational attainment that is forestalling this effect. And until we see educational-status-controlled rates of nonmarital childbearing start to fall, it will still be the case that unmarried childbearing is becoming more normalized within each strata of American society, no matter what the national average numbers may say.

In other words, the recent downturn in nonmarital childbearing may only be a temporary reprieve.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies. He blogs about migration, population dynamics, and regional economics at In a State of Migration.