Highlights

This month, millions of high school seniors across America are making important decisions about which college they will attend for the next four years of their lives. Based on my professional experience talking to high school students considering attending the University of Virginia, where I teach sociology, many of these seniors seem unaware of how much the sacrifices of their parents matter for their odds of taking home a college diploma four years from now.

But matter they do. The practical, emotional, and financial sacrifices parents have made and will make for their children, and for their college education in particular, are enormously important. This brief focuses on one particular dimension of these parental investments: paternal involvement in high school. I find that young adults who as teens had involved fathers are significantly more likely to graduate from college, and that young adults from more privileged backgrounds are especially likely to have had an involved father in their lives as teens.

Family scholars from sociologist Sara McLanahan to psychologist Ross Parke have long observed that fathers typically play an important role in advancing the welfare of their children. Focusing on the impact of family structure, McLanahan has found that, compared to children from single-parent homes, children who live with both their mother and father have significantly lower rates of nonmarital childbearing and incarceration and higher rates of high school and college graduation. Examining the extent and style of paternal involvement, Parke notes, for instance, that engaged fathers play an important role in “helping sons and daughters achieve independent and distinct identities” and that this independence often translates into educational and occupational success.

The Difference Dads Make

Likewise, a US Department of Education study found that among children living with both biological parents, those with highly involved fathers were 42 percent more likely to earn A's and 33 percent less likely to be held back a year in school than children whose dads had low levels of involvement. But little research has examined the association between paternal involvement per se and college graduation.

I investigated that association by using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a study of a nationally representative sample of adolescents who were in grades 7–12 in the 1994–95 school year. The Add Health data indicate that young adults who had involved fathers when they were in high school are significantly more likely to graduate from college.

Specifically, 18 percent of teens reported that their fathers were not involved in their lives. I relied on a scale of adolescent-reported paternal involvement—measuring such activities as playing a sport, receiving homework help, or talking about a personal problem with their biological, adoptive, or step fathers—to divide the remaining portion of teens into roughly equal groups of adolescents with somewhat involved, involved, or highly involved fathers.

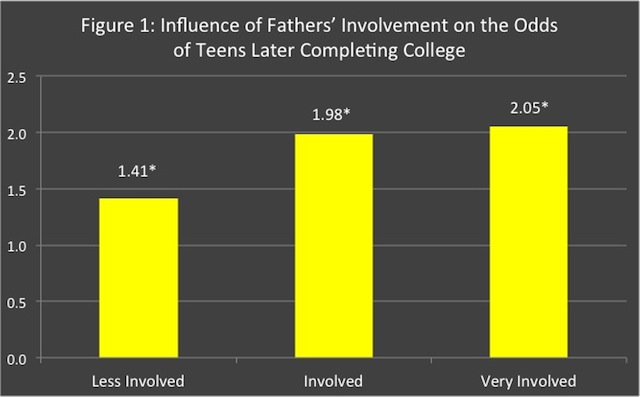

Source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.

Notes: This figure is adjusted for the factors listed below. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) between the group and teens who indicated no relationship with their father, controlling for respondent’s age, race or ethnicity, level of mother’s education, and household income as a teen.

Compared to teens who reported that their fathers were not involved, teens with involved fathers were 98 percent more likely to graduate from college, and teens with very involved fathers were 105 percent more likely to graduate from college (see Figure 1, which adjusts for background factors such as family income, race, ethnicity, parental education, and age). Clearly, young women and men with more engaged fathers are more likely to acquire a college diploma than their peers without such a father.

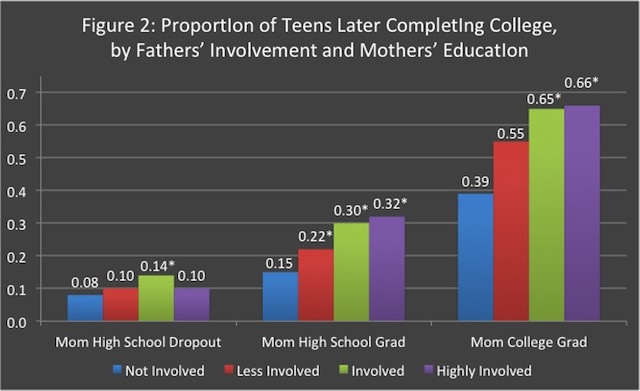

How does this story vary by young adults’ socioeconomic background? Using maternal education as a proxy for socioeconomic status, Figure 2 indicates that, unsurprisingly, young adults from less-educated homes are markedly less likely to acquire a college degree. Nevertheless, this figure—which does not adjust for background factors—also shows that young adults whose mothers were at least high school educated appear to benefit more consistently from having involved fathers in their lives than young adults whose mothers were high school dropouts. In particular, Figure 2 suggests that when it comes to college graduation, though father involvement matters for most young adults, it seems particularly important for young adults from moderately and highly educated homes.

Source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.

Notes: This figure is unadjusted. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) between the group and teens who indicated no relationship with their father, controlling for respondent’s age, race or ethnicity, and household income as a teen.

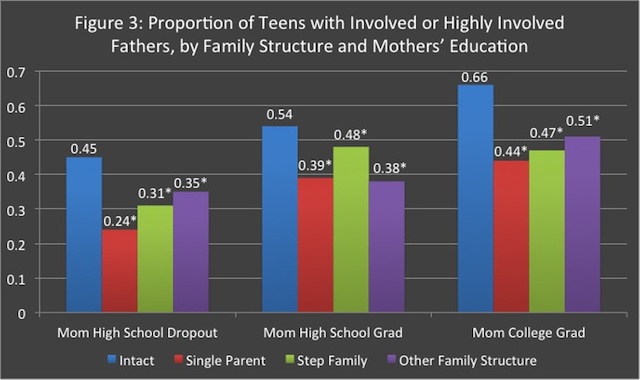

If paternal involvement is important for higher education completion in America, what kind of family structure seems most likely to facilitate such involvement? Figure 3, which does not adjust for background factors, indicates that adolescents are much more likely to report an involved or highly involved father if their biological parents are married. That association between paternal involvement and family structure holds true for families of all education levels. In other words, an engaged approach to fatherhood is more common for adolescents living in an intact, married family, regardless of parental education attainment. But note that the most involved fathers are generally found in homes where the mother is college educated.

Source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.

Notes: This figure is unadjusted. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) between the group and teens from intact families, controlling for respondent’s age, race or ethnicity, and household income as a teen.

Although this brief does not explore in depth the mechanisms that account for the link between paternal involvement and college graduation, four mechanisms seem particularly likely. First, involved fathers may provide children with homework help, counsel, or knowledge that helps them excel in school. Second, involved fathers may help children steer clear of risky behaviors—from delinquency to teenage pregnancy—that might prevent them from completing college. Third, involved fathers may help foster an authoritative family environment (characterized by an appropriate mix of engagement, affection, and supervision) that is generally conducive to learning. Finally, involved fathers may be more likely to provide financial support to children seeking a college education.

However, some other unmeasured factor such as a high-quality marriage or a child’s personality traits may account for the association documented here between high levels of paternal involvement and the odds that a young adult graduates from college.

Conclusion

In today’s global economy, a college diploma has emerged as an increasingly important ticket to achieving the American Dream. Among today’s millennials between ages 25 and 32, every year college graduates earn on average about $17,500 more than their peers with only a high school diploma. A recent Brookings Institution study found that, over a lifetime, a college degree provides an income premium of about $570,000—what this study calls a “tremendous return” on this education investment.

This brief shows that young men and women with involved fathers are significantly more likely to earn a college diploma. Specifically, compared to their peers whose fathers are not involved, young adults with involved fathers were at least 98 percent more likely to graduate from college. Moreover, paternal involvement is especially prevalent among young adults from college-educated homes, and these young adults are also more likely to live in an intact family. This means that young adults from such homes tend to be triply advantaged: they typically enjoy more economic resources, an intact family, and an involved father.

The good news about paternal involvement is that fathers have almost doubled the average amount of time they spend with their children each week, from 4.2 hours in 1995 to 7.3 hours in 2011. The bad news is that partly because fewer adolescents are living in intact, married families, a large minority of the nation’s teens—especially ones from poor and working-class homes—are not experiencing today’s ethic of engaged fatherhood. Thus, if we wish to increase the odds that all young adults have a shot at the higher education of their choice and—by extension—the American Dream, one thing we need to do is figure out how to bridge the fatherhood divide between children from college-educated and less-educated families.