Highlights

- There could be a small subset of people who are on their way to divorcing who do not acknowledge their full unhappiness (to themselves or to others) until they see the ground coming up fast. Post This

- Many people who reported being happy in their marriage on the day surveyed by the GSS will end up divorced. Post This

- Some marriages are "good enough" to provide many benefits to adults and children but not good enough to be ideally protected from turbulence, mechanical difficulty, or pilot error. Post This

While many couples divorce, most people report being happily married when surveyed. Those facts seem at odds. There are some simple and complex methodological explanations for this, but I have long thought about the explanation using a metaphor of an airplane in flight. That is what I present here.

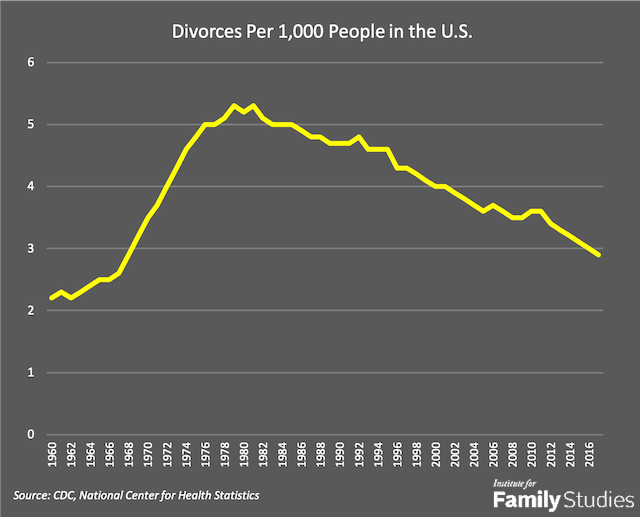

The divorce rate was comparatively low for many years. University of Utah sociologist and IFS contributor Nicholas Wolfinger tells me it has been going up for over 500 years. But I am focusing on a much shorter period of history. In the U. S., divorce started to really take off in the 1960s.1

By the 1980s, demographers were arguing that 50% of couples who married would end up divorcing at some point in life.2 There is room for quibbling about this number because it is a projection. However, the chart above is based on hard numbers (the crude rate per 1000), and it nicely portrays the change. (For more on the complexity of divorce rates, see this article.)

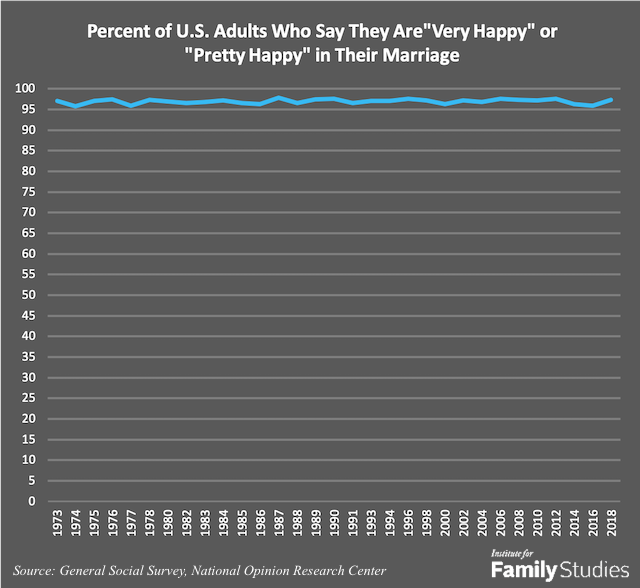

This next chart portrays the percent of married people who said that their marriage was happy when asked, in data from the U.S. General Social Survey.3

The actual question was, “Taking things all together, how would you describe your marriage? Would you say that your marriage is very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?” The chart depicts the percent of people who reported being either “very happy” or “pretty happy” in their marriage. If I presented only the line for the percent saying their marriage was very happy, it would average around 63% (you can check for yourself right here).

The divorce data and happiness data are quite different (and not merely because the data I could most easily retrieve on divorce go back further in time than the happiness data). The divorce data are official statistics for the entire country; they are population-level data of couple outcomes. The marital happiness ratings are individual-level data from cross-sectional surveys that reflect sentiments at the moment surveyed. There are vast methodological and conceptual differences in these types of data. My focus here is on the sense of a paradox presented by the two facts—facts represented by the shape of these lines. To many people, it is not immediately obvious how divorce can be so common while most people report being happily married.4

Ponder those charts above, especially from 1985 onward. Divorce had really taken off by then. Boomers were at the forefront of this change, and they are still going at it.5 Sociologist Susan Brown and colleagues have written extensively about the grey divorce revolution, and the boomers are a big part of it.6 But even couples marrying now still have a substantial lifetime probability of divorce, perhaps somewhere a bit under 40% for first marriages. That could be high or low. (Again, I wrote an article on that if you want to think more about it.)

I have a metaphor for addressing the paradox. Metaphors can be useful, within boundaries.

Taking Flight

Airplanes fly high above the clouds most of the time. Some crash, but most planes, most of the time, are flying somewhere above 30,000 feet (at least, passenger airlines are). You could poll pilots during flights, and your reports will average out at high elevations. That does not represent the trajectory of entire flights, nor is the happiness chart above showing trajectories of happiness across time in marriages. Many people who reported being happy in their marriage on the day surveyed by the GSS will end up divorced. That’s really the primary cause of the paradox, I think.

I have long imagined marital trajectories as airplane flights. Researchers have, of course, considered trajectories in more sophisticated ways.7 In my metaphor, altitude is happiness and a crash is a divorce. Of course, some divorces may be better typified as landings short of the original destination, but let’s keep things simple for the metaphor. Here, a crash pertains to the marriage being over.

Long flight, high altitude, no major malfunctions, safe landing. That’s a long-term, happily married couple completing the flight plan most every marrying couple hopes to fly. The plane may have to fly around a thunderstorm or two, but it’s mostly steady, level flying. Paul Amato and Spencer James published a paper in 2018 that describes these couples pretty well, showing that most marriages that last are quite happy over the long haul. Not all couples, of course, but most. In contrast, they showed that those flying ahead of an eventual crash, were, over time, increasing in discord, spending less leisure time together, and were declining in happiness.

Short flight, low and fluctuating altitude, with a crash shortly after take-off. That’s a couple who blows apart early in a marriage. There could be many reasons why. Some of the planes had a major problem that was overlooked before taking off. Here, just note that the early years of marriage are the time of the highest risk for divorce,8 not unlike how the time just after take-off is the highest risk for airplanes.

Long flight, lower altitude, high turbulence, but no crash. While most flights are above 30,000 feet at any given moment, some planes never get above 10,000. There are not really many commercial airplane flights like this, but there are marriages like this. If we just tracked the elevation for such a flight over time, it may fluctuate between 200 and 10,000 feet. There would also be more turbulence because the plane is flying lower to the ground. This is a couple who likely was pretty happy at some point, but, for most of their marriage, they are not too happy. However, they stay together either by determination or because of high constraints.

Long flight, mostly at high altitude, with a sudden loss of altitude and a crash. This is the couple that seemed to be doing fine until something massively destabilizing happened. A wing came off, the engines failed, or a rapid and catastrophic decompression resulted from a door falling off. Something emergent overcame the static dynamic of a smooth, level, high-altitude marriage: an affair, cancer and its soul-sucking stress, or the death of a child. Hard stuff where there was not enough elevation to stay in the sky. Among these higher-flying marriages, some come to an end in what seems a moment, and others will steadily lose altitude for a longer period of time before the end, but much of the flight before that seems to have been at a reasonably high elevation. If the GSS folks had asked such a couple to check their altitude, just by probability, they would have been more likely to get asked about their happiness while the plane was high than when it was coming down, because they were most likely happier in their marriage for a longer period of time.

These are a sampling of many possible trajectories for how a marriage goes. You can see how they reflect the difficulty of reconciling the two types of data.

A lot of people are very happy in their marriages. Many will stay that way with only a few ups and downs. Others will experience a slow or rapid loss of what holds them together. Some will have emergency descents and recover.

Complexities

Dynamics within relationships tend to be stable.9 Matthew Johnson at the University of Alberta puts it this way: “Stability seems to be the norm, and when change happens, it’s usually not for the better.” While there will be many exceptions, marriages with challenging dynamics at 10 years likely had evidence of those dynamics before the couple got married. Ted Huston and colleagues labeled this phenomenon, “enduring dynamics.” For example, some couples were never able to fly smoothly or at high elevation because of difficulties in communicating or being emotionally supportive. Relationships have stable characteristics, and so do the individuals in them. Psychologist Dan Wile has observed,

When choosing a long-term partner, you will inevitably be choosing a particular set of unsolvable problems that you’ll be grappling with for the next ten, twenty or fifty years.

That seems right in that it’s real. No one gets perfection, and no one is offering it.

There is a strong corollary to the stability of overall happiness in life. People are remarkably likely to hover around a particular set point. Even after consequential life events, for better or for worse, people tend to return to a level of happiness much like where they were beforehand. This has been called the hedonic treadmill. A lot of the things that matter in life are pretty stable within the lives of individuals. (I hope that is good news for you.)

That there were plenty of people surveyed by the GSS who reported that their marriage was pretty happy (34%) but not very happy (63%) reminds me of Paul Amato’s concept of “good enough marriages.”10 These are marriages good enough to provide many benefits to adults and children but not good enough to be ideally protected from turbulence, mechanical difficulty, or pilot error. These marriages are beneficial, but they are also at greater risk of abrupt contact with the ground.

When marriages do come apart, people give various reasons. Their stories may not be the most accurate data in the world, because individuals may be a little biased and spouses may not agree, but this information is still useful. However, just like with airplanes that have crashed, the best information would come from continuously-recorded data during flight—kind of like the black boxes used in airplanes. In social science, that means longitudinal data at close enough intervals to answer questions about what happened and when. Such research is expensive, and further complicated by the complexity and assumptions of analyses.11 I started this piece with data that are fundamentally very simple.

There is one other element to ponder here. My colleague Galena Rhoades and I have noticed a pattern in various surveys gathered over the years in the lab projects we are overseeing with our colleague, Howard Markman at the University of Denver. Across various studies, the number one item we see left blank is the single-item asking about how happy one’s relationship is—very much like the item used in the GSS. We suspect—but have not tested this— that some people are psychologically defended against acknowledging their true level of relationship (un)happiness, so they leave the question blank. That could be protective for some people and a risk for others. The idea behind this may be relevant here, in that there could be a small subset of people who are on their way to divorcing who do not acknowledge their full unhappiness (to themselves or to others) until they can do nothing other than see the ground coming up fast.12 Because of all these complexities, divorce is a much more definitive measure than marital happiness, but both are obviously important.

Let’s Land

A lot of people are very happy in their marriages. Many will stay that way with only a few ups and downs. Others will experience a slow or rapid loss of what holds them together. Some will have emergency descents and recover. The paradox I started with is explained by the fact that, at any given time, the planes currently flying are mostly all pretty high or very high in the sky. A survey like the GSS is not optimal for sampling plummets.

For those making the trip. While there are known factors associated with which marriages are most likely not to make it, the ability to predict divorce for any given couple is over-rated.13 If it were easy to predict who would crash, no one would ever board some of the planes that take off. Still, there is a lot of information about what makes it more or less likely that a couple will struggle with happiness and/or divorce. Years ago, I wrote a piece that gets into this, including advice to singles for lowering their risks. Humans do not change easily, but there are some strategies for working to change one’s level of risk. If your plane is well into its flight, I wrote something for married couples, too.

Here, I have tried to explain the paradox of how so many couples divorce while so many people report being happy in their marriages. Did I succeed? You be the judge. How happy are you with my metaphor? Would you say you are “very happy,” “pretty happy,” or “not too happy”?

* * *

Postscript: Want to take another flight with me? Here’s a favorite piece of mine that hovers around the nature of happiness in marriage and family, focused on the transition to parenthood. I discuss how measures of happiness may miss something deeper about meaning. And it’s also about airplanes: Cleanup on Aisle 9 at 35,000 Feet.

Scott M. Stanley is a research professor at the University of Denver and a fellow of the Institute for Family Studies (@DecideOrSlide).

1. There are various metrics for this. I am using the crude number of divorces per 1000 people from U.S. data, mostly from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/marriage-divorce.htm. I made this chart from data easily found online. If you are a demographer and feel like it is off somehow, just let me know. These data are only as good as state collection and reporting, and you can see in footnotes at the link above. In some years, various states did not get their numbers in or such numbers were not available. If you want more on the complexity of the divorce rate and trends, a gift that keeps on giving to family social science, here you go: https://ifstudies.org/blog/what-is-the-divorce-rate-anyway-around-42-percent-one-scholar-believes.

2. I originally thought that Paul Glick was the first to make the more sophisticated projection of the likelihood of divorcing in 1984, but Phil Cohen recently noted on Twitter that the first projection of this sort was likely this one by Samuel Preston (in 1975). These and subsequent projections made by the CDC and others were based on careful consideration of the likelihood of divorcing at various ages and stages of marriage/life. Contrary to a myth, they were not based on the observation that, year after year, there are about twice as many marriages as divorces. You might quibble with 50%. Many people have. I think the projections were likely pretty good, and that the projected probability of divorcing was, indeed, around 50% for years. It’s come down some, and the subject is complex.

3. I used the GSS Data Explorer to get these numbers: https://gssdataexplorer.norc.org/trends/Gender%20&%20Marriage?measure=hapmar

4. There are a number of works that highlight conceptual or empirical differences between marital happiness (an indicator of relationship quality) and divorce (an indicator of stability), including these: Wolfinger, N. H. Understanding the divorce cycle: The children of divorce in their own marriages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).; Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (1992). Assessing commitment in personal relationships. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54, 595-608.

5. Conflict of interest statement. I am a Boomer, but on the trailing edge. That’s why I look so young.

6. For more on the boom in divorce for older Americans, here you go: https://www.bgsu.edu/arts-and-sciences/sociology/Research/Gray-Divorce.html

7. For example, Anderson, J., Van Ryzin, M. J., & Doherty, W. (2010). "Developmental Trajectories of Marital Happiness in Continuously Married Individuals: A Group-Based Modeling Approach," Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 587-96. See also an example of the emerging emphasis on thinking about trajectories in relationship development, here: Eastwick, P. W., Keneski, E., Morgan, T. A., McDonald, M. A., & Huang, S. A. (2018). "What do short-term and long-term relationships look like? Building the relationship coordination and strategic timing (ReCAST) model," Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147 (5), 747-781.

8. It has been surprisingly difficult to find the single best citation for this fact. Here is a minimal note about this on my blog, with some helpful data from Nick Wolfinger, that he dug out of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). You can also see how this is true in a table provided in the following paper, but it is not optimized to make this point: Raley, R. K., & Bumpass, L. (2003). "The topography of the divorce plateau: Levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980," Demographic Research, 8, 245-260.

9. For example, Huston, T. L., Caughlin, J. P., Houts, R. M., Smith, S. E., & George, L. J. (2001). "The connubial crucible: Newlywed years as predictors of marital delight, distress, and divorce," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 237-252.; Lavner, Justin & Bradbury, Thomas. (2019). "Trajectories and maintenance in marriage and long-term committed relationships," Journal of Family Psychology; Williamson, H. C., Nguyen, T. P., Bradbury, T. N., & Karney, B. R. (2016), "Are problems that contribute to divorce present at the start of marriage, or do they emerge over time?" Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33 (8), 1120–1134. Markman, H. J., Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., Ragan, E., & Whitton, S. (2010). "The premarital communication roots of marital distress: The first five years of marriage," Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 289-298.

10. Amato, P. R. (2001). "Good enough marriages: Parental discord, divorce, and children's well-being," The Virginia Journal of Social Policy & the Law, 9, 71-94.

11. If you are a researcher who has gotten this far, you’ll recognize that a critical aspect in this is having ways to get at both between group differences and within-person changes over time.

12. It adds to the complexity in all this that happiness is individually rated and divorce is dyadically experienced. They are not the same in this and many other ways.

13. This is brilliantly addressed in a piece by colleagues I much admire, Rick Heyman and Amy Smith Slep: Heyman, R. E., & Smith Slep, A. M. (2001). "The hazards of predicting divorce without cross-validation," Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 473-479.