Highlights

- A recent study documented that children being reared in cohabiting unions in 27 African and Latin American countries were at a decided advantage across five different outcomes. Post This

- It is striking that even in contexts where married couples are disadvantaged, there are hints that marriage itself may be helpful for children. Post This

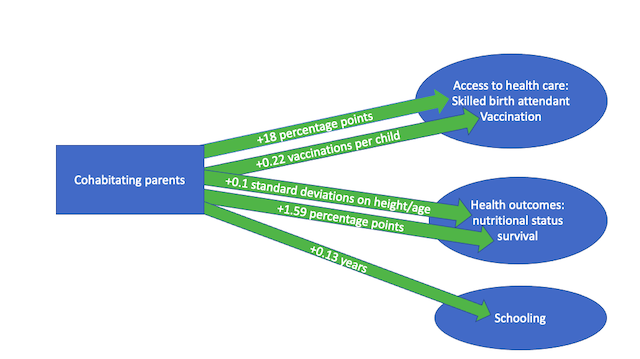

Hayley Pierce and Tim B. Heaton compared children's outcomes across cohabiting and marital unions in 27 African and Latin American countries. Their recent study documented that children being reared in cohabiting unions in these countries were at a decided advantage across five different outcomes. They were more likely to: have a skilled attendant at their birth, have received more vaccinations, have had better nutritional status, to survive to age five, and to have received more schooling.

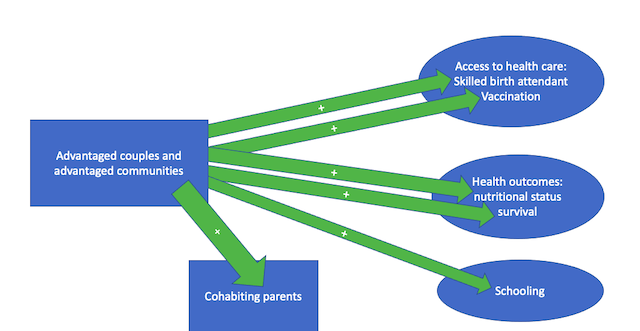

Pierce and Heaton expected that the advantages accruing to children of cohabitants could be explained by the characteristics of their parents and the community context, rather than being explained by cohabitation per se. In other words, they hypothesized that this positive association was spurious. Something more like this:

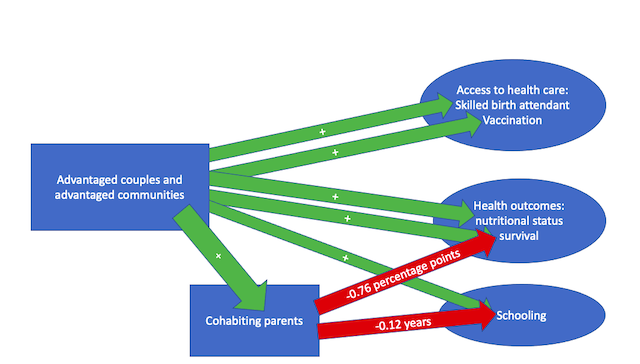

So, they anticipated that when they tested for direct relationships between cohabitation and the children's outcomes, there would be none. This is what they found:

The positive association between having cohabiting parents and three of the outcomes—having a skilled attendant at birth, vaccination, and nutritional status—was fully explained by cohabiting parents having advantageous characteristics (e.g., being less likely to condone domestic violence, being more likely to live in an urban area). The positive association between having cohabiting parents and the other two outcomes—surviving to age five and number of years of schooling—was also explained away in the same manner. Therefore, Pierce and Heaton concluded that children with cohabiting parents are at no clear advantage compared to children of married parents.

I interpret their results differently. It looks to me like their hypothesis was right for three of the outcomes (no remaining association after including couple and community characteristics), but that they underplayed the disadvantage associated with cohabitation for child survival and schooling.

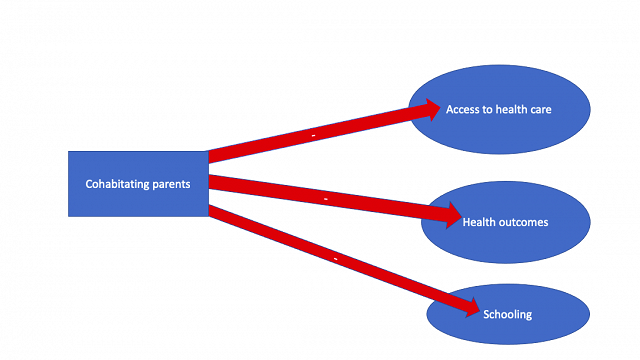

In Europe and the United States, cohabitation has been described as a "poor man's marriage" because it often occurs within a context of poverty and instability, unlike in the countries Pierce and Heaton studied where it is often correlated with advantage. Therefore, parental cohabitation is associated with the following negative child outcomes. But these negative associations could be spurious, driven by the fact that advantaged couples are more likely to marry.

The disadvantageous child outcomes associated with parental cohabitation can sometimes (though not always) be explained away by controlling for couple and neighborhood characteristics. But Pierce and Heaton's discourse departs from that commonly found in studies of Northern countries. Instead of remaining focused on the gap in child outcomes associated with cohabitation, they devote more attention to the narrative of Developmental Idealism, which focuses on the attitudinalchanges that accompany growth in national income, urbanization, and other indicators of development, like thinking that small families are good and that women should have rights. The idea that whether to cohabit or marry is an individual choice accompanies this package.

Thus, Pierce and Heaton emphasize that where Developmental Idealism spreads, cohabitation will become more common, and that the whole package will produce better child outcomes. I agree. They explained:

Children living in informal unions have other advantages. Their households are smaller, and more urban. Compared with children of mothers in formal marriages, children of mothers in informal unions have more educated mothers, a smaller age gap between parents, mothers with more involvement in decision-making, longer intervals between births, and mothers less tolerant of domestic violence.

But better overall child outcomes do not mean that every part of the package has helped. In fact, Pierce and Heaton seem to disregard their own evidence that children of married parents are more likely to survive and attend school longer than children of cohabiting parents. They say "descriptive analysis suggests that informal unions are a positive context for child health and education in less developed countries" without considering that this positive context could coexist with cohabitation itself having a negative causal effect.

I am not arguing that Pierce and Heaton's results demonstrate a causal advantage to marriage; data from Southern countries generally do not have the characteristics necessary to support causal inference.1 Nonetheless, it is striking that even in contexts where married couples are disadvantaged, there are hints that marriage itself may be helpful for children. These should not be ignored.

Laurie DeRose is a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the Catholic University of America, and Director of Research for the World Family Map Project.

1. For instance, the negative association between current cohabitation and years of schooling could result from past marital instability that disrupted schooling and also resulted in a new union. In that case, past marital instability could be a common cause of both current cohabitation and compromised schooling.