Highlights

- Living together outside of marriage is now accepted by most Evangelicals. For those under 45, most have cohabited, plan to do so in the future, or are open to the possibility. Post This

- Among Evangelicals who have ever cohabited, only 49% of first cohabitations culminated in marriage by the time they were surveyed. Post This

Most of us are used to seeing well-known Evangelicals who live together outside of marriage celebrated in the news media—without any suggestion of a contradiction between their claims to be Bible-believing Christians and their choice to cohabit. Recent examples include top-rated Kansas City Chiefs Quarterback Patrick Mahomes and A-list Hollywood actor Chris Pratt.

Pratt and Mahomes are not anomalies; living together in sexual union outside of marriage is now accepted by most Evangelicals. Among those under 45, most have practiced cohabitation, plan to live together in the future, or are open to the possibility. As I document in a recent article in Christianity Today, cohabitation is a “new norm among young, professing evangelicals.” It is stunning that this has quietly come to pass among adherents to a form of Christianity that emphasizes radical obedience to an inerrant Bible, forbids all sex outside marriage, and emphasizes being distinct from “the world.”

A Pew Research Center study in 2019 documented the acceptance of cohabitation among most Evangelicals. Specifics that I received directly from the authors showed that 58% of white Evangelicals say they believe that cohabiting is acceptable if a couple plans to marry. In this survey, younger cohorts were far more liberal. In fact, by 2012, the General Social Survey (GSS) revealed that only 41% of evangelicals ages 18 to 29 disagreed with the claim that cohabitation was morally acceptable even if the couple had no express intention to marry.1

Here, I examine some key data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), combining the separate male and female respondents. First, I compare evangelicals with other Christian religious groups as well as those of no religious affiliation (“Nones”), using the most recent cycle of the NSFG (2017–2019). Then, I combine the last three cycles to examine variation within evangelicals by church attendance and the self-identified importance of religion2 to daily living.3

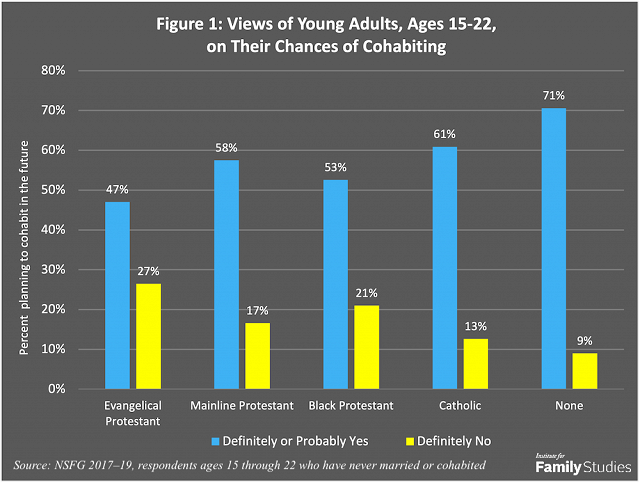

The NSFG asks respondents who are not currently cohabiting or married if they think they are likely to cohabit in the future. Because I wanted to focus on young people’s views, I narrowed my focus to only those respondents who were 15 to 22 years of age who had never been married or cohabited . The results are shown in Figure 1. Evangelical Protestants are clearly the least likely to say it is likely they will cohabit someday and are the most likely to have ruled cohabiting out. Still, only about one in four gave the “Bible answer” of “definitely not,” and close to half are planning on or leaning toward it.

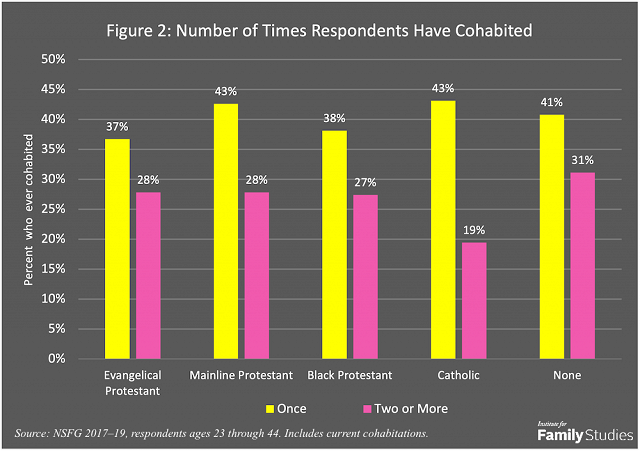

Next, I considered whether respondents had engaged in cohabitation and if so, if they had done so more than once. This is summarized in Figure 2, which focuses on ages 23 to 44.

Evangelical Protestants are not as different as we might expect: 65% have cohabited, essentially the same as Black Protestants (66%) and Catholics (63%).

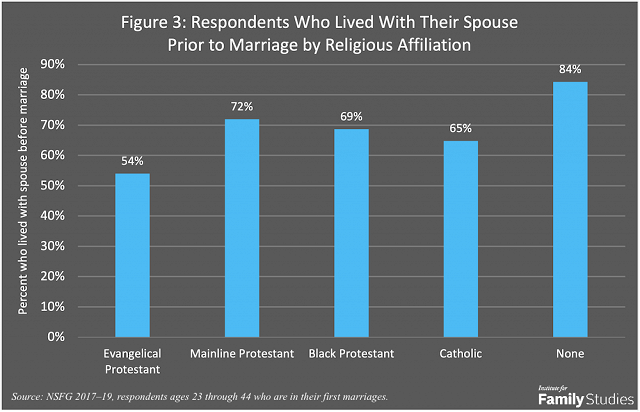

Figure 3 shows the percentages who lived with their spouse prior to marriage for all respondents between the ages of 23 and 44 who are currently in their first marriage. The Evangelical percentage is substantially lower than those for other religious identities. Still, in 54% of intact, first evangelical marriages, the couple had lived together first.

Plans to Marry

In Evangelical circles, the argument sometimes is that evangelical cohabitation is different from “worldly” cohabitation because it is overwhelmingly tied to impending marriage. But the facts suggest otherwise. Among Evangelicals who have ever cohabited, only 49% of first cohabitations culminated in marriage by the time they were surveyed.4 Evangelicals are not very different from Catholics (45%) and Mainline Protestants (who get married slightly more often—53%) on this issue. Among female Evangelicals who have ever cohabited, only 18% were formally engaged when they moved in with their first cohabiting partner, and another 18% had definite plans to marry; thus, only 36% combined had serious marital intent.5 Formal engagement upon the commencement of first cohabitation was higher for female evangelicals (the closest being Catholic at 15%). However, if we combine percentages for formal engagement and definite plans, Evangelicals are essentially the same as Black Protestants (37%) and Catholics (34%).

Among the currently cohabiting, only 55% of cohabiting Evangelicals were certain they would marry their partners—less than Mainline Protestants (59%), but more than the other religious groups. Of these Evangelicals, 13% were living with partners they had no clear intention of marrying; about the same as for Catholics (12%).6

There is solid research that suggests that those who do not move in together until they already have firm plans for marriage, and especially are formally engaged, may not have higher risk of divorce compared to those who choose not to live together until after they are married. They certainly have much lower risk of divorce than those who marry following cohabitations that were not preceded by wedding plans. However, this does not describe most Evangelical cohabitation.

Religious Commitment

What role does religious commitment play among Evangelical plans and practices related to cohabitation? I addressed this question by combining the last three cycles of the NSFG. Specifically, I looked at church attendance, and whether respondents regarded their religious faith as “very” or only “somewhat” important to their daily lives.7 Examining young people’s thoughts about future cohabitation and older respondents’ experience with it seemed sufficient for this brief report.

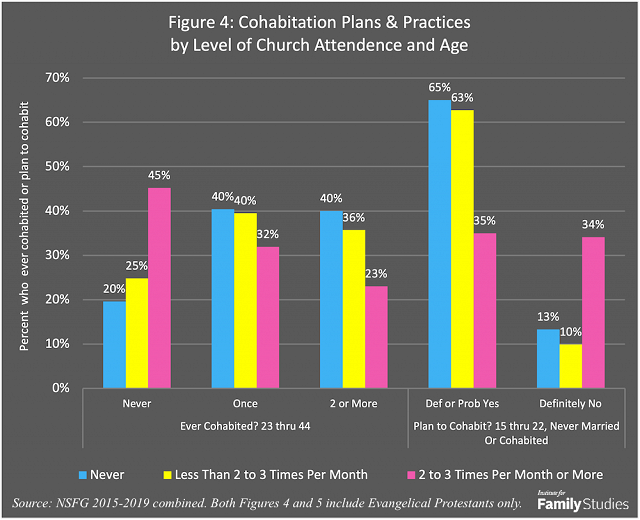

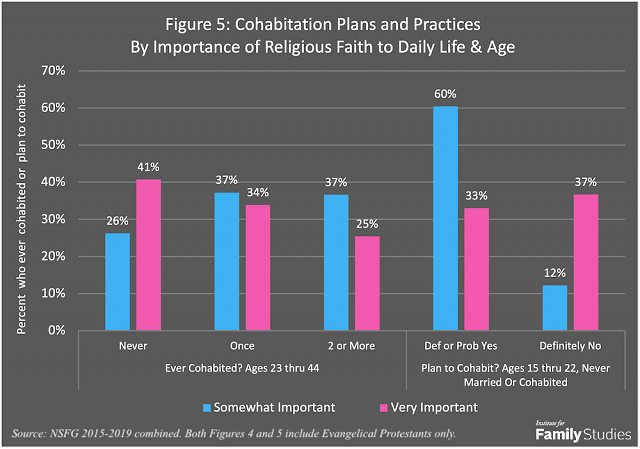

As Figures 4 and 5 show, both church attendance and self-identified importance of religious faith are strongly related to plans to cohabit among younger evangelicals and to having actually done so—among those who are older. This was not only true overall, as shown in these figures, but held for men and women separately.8

On the one hand, Evangelicals who are the most committed to their faith have cohabitation plans and practices that are much more likely to be in line with accepted Evangelical positions. On the other hand, even among these “ideal” Evangelicals, most respondents ages 15 to 22 are not determined to forego living together until marriage, and most respondents ages 23 to 44 have cohabited. In fact, roughly one-quarter of those who attend church regularly have cohabited two or more times, and most have done so at least once.

The rise in cohabitation over the past few decades has been sharp across the developed world, including the United States. Despite the teaching of their faith, Evangelicals have not proven to be much of an exception. If Evangelical leaders wish to turn this ship around, they will need to explore fresh approaches to addressing this issue.

David Ayers is a Professor of Sociology in the Department of Economics and Sociology at Grove City College. He is author of the forthcoming Beyond the Revolution: Sex and the Single Evangelical (Lexham, 2021) as well as Christian Marriage: A Comprehensive Introduction (Lexham, 2019).

1. In both the General Social Survey and the National Survey of Family Growth, I use the highly regarded “RELTRAD” schema for classifying Christian denominations. The NSFG uses this directly. For the General Social Survey, I used the Stetzer and Burge syntax from the syntax repository at the Association of Religion Data Archives. Please note that the designation “Black Protestant” refers to a group of denominations that are historically black, such as the National Baptist Convention and the African Methodist Episcopal Church, not simply to Protestants who are African Americans. This is part of the RELTRAD schema.

2. When combining the NSFG male and female respondent files, females exceed males 54% to 46% for the 2017—2019 cycle. When combining the last three cycles (2013—2015 through 2017—2019) the difference was 55% to 45%. A weight variable was applied in both cases to correct for this. I do not look at respondents older than 44, to maintain consistency since ages 45 to 49 have only been included in the last two cycles of the NSFG.

3. All overall differences between religious groups and—among evangelicals—between levels of church attendance and self-identified importance of religious faith, in cohabitation plans and practices, that are discussed in this report, are statistically significant unless indicated otherwise.

4. Whether or not it subsequently ended in divorce.

5. The manner in which males were asked about engagement to former cohabiting partners is not exactly comparable, so I focus only on females here.

6. These differences among religious groups were not statistically significant.

7. Among evangelicals the numbers who answers “not important” are too small to analyze here.

8. Both Figures 4 and 5 include Evangelical Protestants only, and combine the NSFG for 2015–19.