Highlights

Many studies have found that young people raised in single-parent families show more achievement and behavior problems than those who grow up with both their biological parents. Family sociologists often attribute these developmental problems to the meager financial resources that single parents command, and the less adequate supervision they can exercise over their offspring. But research has also shown that childhood disturbances are linked to conflict between parents, especially when the conflict is intense or prolonged. My analysis of recent national survey data here shows that children of divorced and never-married parents are far more likely to have been exposed to domestic violence than children in married two-parent families.

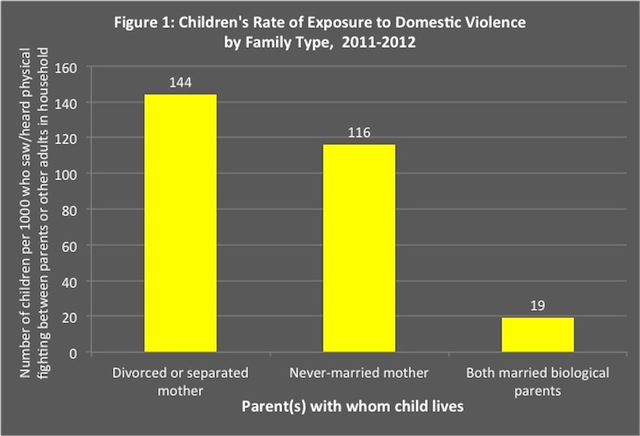

In the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health, conducted by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, parents of 95,677 children aged 17 and under were asked whether their child had ever seen or heard “any parents, guardians, or any other adults in the home slap, hit, kick, punch, or beat each other up.” Among children living with both married biological parents, the rate of exposure to family violence was relatively low: for every 1,000 children in intact families, 19 had witnessed one or more violent struggles between parents or other household members. By comparison, among children living with a divorced or separated mother, the rate of witnessing domestic violence was seven times higher: 144 children per 1,000 had had one or more such experiences. (See Figure 1.) These comparisons are adjusted for differences across groups in the age, sex, and race/ethnicity of the child, family income and poverty status, and the parent’s education level.

Source: Zill, N. (2014). Analysis of public use microdata file from 2011-12 National Survey of Children's Health, National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

One might suppose that women who had never married would be less likely to get into violent arguments with the fathers of their children than separated or divorced mothers. Yet the rate of witnessing domestic violence among children living with never-married mothers was also elevated. It was 116 per 1,000, six times higher than the rate for children in intact families. (Some of these fights involved subsequent partners or boyfriends of the mother, rather than the father of the child.) Even children living with both biological parents who were cohabiting—rather than married—had more than double the risk of domestic violence exposure as those with married birth parents: 45 out of 1,000 of these children had witnessed family fights that became physical. Note also that a child’s family structure was a better predictor of witnessing family violence than was her parents' education, family income, poverty status, or race.

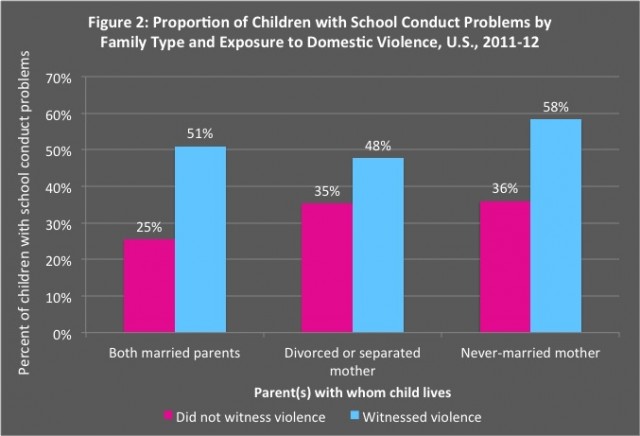

Experiencing family violence is stressful for children, undercuts their respect and admiration for parents who engage in abusive behavior, and is associated with increased rates of emotional and behavioral problems at home and in school. For example, among children of never-married mothers who had witnessed family violence, 58 percent had conduct or academic problems at school requiring parental contact. The rate of school behavior problems for those who had not been exposed to family fights was significantly lower, though still fairly high (36 percent). Likewise, among children of divorced or separated mothers, nearly half of those exposed to family violence—48 percent—had had conduct or academic problems at school. Even among the small number of children in intact families who had witnessed family violence, just over half—51 percent—presented problems at school. This was twice the rate of school problems among students from intact families who had not witnessed domestic violence. (See Figure 2.) These figures are also adjusted for differences across groups in age, sex, and race/ethnicity of children, family income and poverty, and parent education levels. Children experiencing domestic violence were also more likely to have repeated a grade in school and to have received psychological counseling for emotional or behavioral problems. This was true in intact as well as disrupted families.

Source: Zill, N. (2014). Analysis of public use microdata file from 2011-12 National Survey of Children's Health, National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Why are children in disrupted families more likely to experience domestic violence? Physically aggressive behavior on the part of one partner sometimes leads to the couple divorcing or not getting married in the first place. But the dynamics of the divorce process tend to increase the probability of one or both partners becoming frustrated and angry. The legal system encourages combat rather than cooperation between litigants. The “loser” in a custody dispute may be prevented by court order from seeing his or her children as often as he/she would like. Or the child support judgment may impose onerous financial obligations. It is a well-established psychological principle that extreme frustration leads to aggression, particularly in individuals with low impulse control and aggressive tendencies to begin with. Sexual jealousy may play a role as well, as one or both parents develop new intimate relationships. Such relationships are rarely symmetrical. There is almost always more lingering hurt, resentment, and feelings of loneliness or abandonment on the part of one member of the original couple than the other.

In the case of parents who never marry, a new boyfriend or girlfriend frequently assumes a step-parental role, whether formally or informally. This can lead to conflict over the legitimacy of the substitute parent’s authority over the children, differences in parenting styles or willingness to tolerate disobedient behavior by the children, or the non-resident biological parent feeling that he or she is being displaced. Cases of child neglect and abuse often involve a boyfriend or girlfriend caregiver who does not have biological ties to the child victim.

Despite increases in the proportion of young people being raised in single-parent families, rates of domestic violence have actually fallen in recent decades. Less tolerant public attitudes about partner battering, more stringent enforcement of domestic abuse laws, and the greater financial independence of women have likely played a part here. The NSCH data provide another insight into the trend: Children born to mothers who were teenagers or young adults (ages 20–24) at the time of the child’s birth were more likely than those born to older mothers to have witnessed family fights that became physical, and there has been a steep decline in the numbers of children born to teen and young adult mothers. But no matter the age of the mother, children in intact families are less likely to have witnessed domestic violence than those in disrupted families.

Nicholas Zill is a psychologist and survey researcher who has written on indicators of family and child wellbeing for four decades. Prior to his retirement, he was the head of the Child and Family Study Area at Westat, a social science research corporation in the Washington, D.C., area.