Highlights

- Having married parents typically means that children live in families with more resources, including more time with their parents, and with greater stability. Post This

- There are roles for both policy and civil society in promoting and supporting marriage. Post This

- Study after study shows a strong correlation between marriage and a wide array of positive outcomes, and also shows that the benefits of marriage are larger than would be predicted by economic factors alone. Post This

Editor’s Note: What follows is a chapter from Rebalancing: Children First, a new report from the AEI-Brookings Working Group on Childhood in the United States.

Our working group agrees that the research evidence indicates that, on average, children who have (a) two parents who are committed to one another, (b) a stable home life, (c) more economic resources, and (d) the advantage of being intended or welcomed by their parents are more likely to flourish. In general, we believe that evidence suggests that marriage is the best path to the favorable outcomes highlighted above. Marriage is of course not the only path that allows children to succeed; many children raised by single parents and cohabiting parents thrive in life. Even so, in the United States marriage continues to be the institution most likely to combine the four benefits outlined above for the sake of children.

Marriage matters to children. Having married parents typically means that children live in families with more resources, including more time with their parents, and with greater stability. While these factors in themselves point to a range of improved outcomes for children, the benefits of growing up in a family with married parents is more than a sum of these parts. Yet a long, steady decline in marriage rates over the past five decades means that more children are growing up in single-parent families. Today about one in four children ages 0–12 does not have married parents. While the decline in marriage has occurred across all demographics, more than one in three children whose mother has an education level of less than a college degree does not have married parents.1

Of course, marriage does not guarantee an environment in which children get what they most need—a secure and stable environment with engaged and nurturing caregivers. But, in our review of the evidence, the working group concludes that marriage offers the most reliable way to promote these ends. We underline that the differences in outcomes we have been discussing are primarily the rates at which children experience adversities; most children from single, step, and cohabiting families do well or average on most outcomes (D’Onofrio and Emery 2019; Eggebeen and Licher 1991; Hetherington and Kelly 2002). In other words, many children from nonintact families thrive.

There are roles for both policy and civil society in promoting and supporting marriage, including targeted reductions of marriage tax penalties, improved economic opportunities that will in turn promote marriage, and communication of clear public messages about the importance of marriage for children.

Family Structure and Stability in the U.S. Context

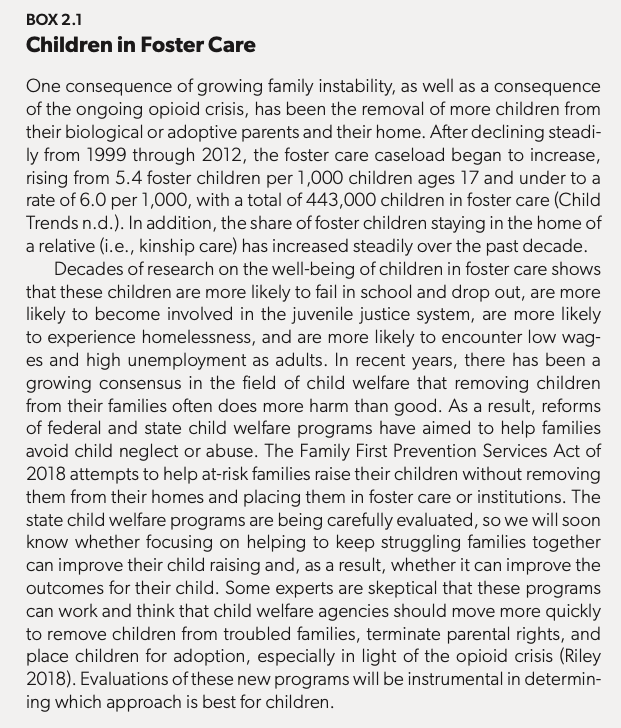

Over the past half century, marriage has become less likely to anchor the lives of American families, leaving more and more children to experience family instability and single parenthood. As shown in figure 2.1, the percentage of children (ages 12 and under) living in households with married parents (with spouse present) declined from 83 percent in the mid-1970s to 71 percent in 2019. This decline in children living with two parents was accompanied by a steady increase in the percentage of children living with only their mother. This trend was entirely driven by a rise in the share of children living with never-married mothers, which increased from 3 percent in 1976 to 18 percent in 2019. The share of children living with divorced mothers held relatively steady over this period at 6 percent (Cherlin 2009; Cohen 2019).

Changes in family life have not affected all children equally. Children with less-educated parents and Black and Hispanic children have been disproportionately affected. Over the past 40 years nonmarital childbearing rose the most for families in these two groups (Cherlin 2009; Wilcox and Marquardt 2010). As shown in figure 2.1, two-thirds of children ages 12 and younger with mothers with less than a college degree had married parents in 2019, down from more than 80 percent in 1976. The decline in marriage has been much less steep for college-educated mothers, dropping from 93 percent in 1976 to about 90 percent in 2019. Among mothers with a college degree, 14 percent of the decline in marriage rates is explained by an increase in divorce, 75 percent is explained by an increase in never-married mothers, and the remainder is explained by an increase in the small share of mothers that are separated or widowed.

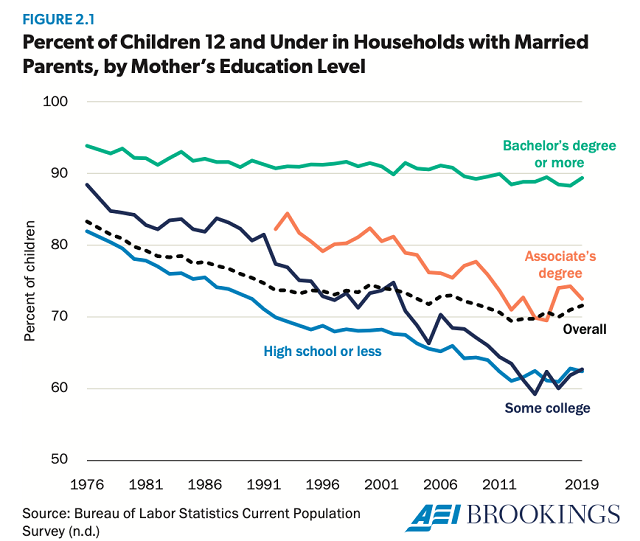

Today, when it comes to both socioeconomic status and race, American family life is deeply unequal (figure 2.2). Much of the difference across racial and ethnic groups likely reflects group differences in economic conditions, including differences in wages and employment opportunities (Sawhill 2013), differences in wealth including home ownership rates (Schneider 2011), as well as differences in educational attainment (figure 2.1). An increasing share of children across all groups lived with a never-married mother in 2018. In 2018 more Black children lived with never-married mothers than with married parents. Fewer than two in five Black children lived with married parents in 2018, compared with two in three Hispanic children and 82 percent of white children. After rising for most groups between 1976 and 2000, the proportion of children living with separated, divorced, or widowed parents in 2019 is about the same as it was in 1976: 6 percent of Hispanic children and 6 percent of white children, and 8 percent of Black children ages 12 and under.

Since the Great Recession, declines in marriage rates have halted—at least from the perspective of children. Divorce has fallen by more than 20 percent since the onset of the Great Recession, nearly returning to 1970 levels (Payne 2018). The share of children living with married parents has edged up by a percentage point since 2011, driven by a decline in the share living with divorced parents; in addition, nonmarital childbearing declined by a percentage point since 2009 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2019). Especially striking about this modest reversal is that it has been largest for Black and Hispanic children. In other words, in recent years the share of children in married-parent families is rising faster for Black and Hispanic children than it is for white children, though the gaps in levels remain large. So even though stark inequalities still exist, American families have become somewhat less unequal in the past decade.

Evidence That Family Structure and Stability Matter for Children

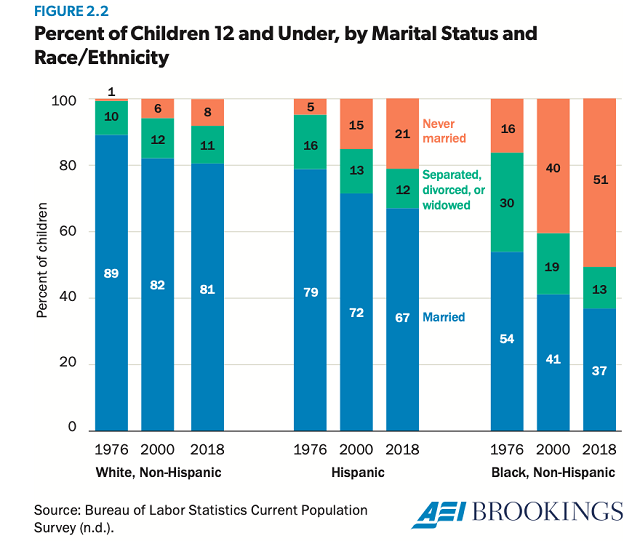

The family divide in America has many roots, but it has been largely driven by changes in our economy and in our culture that have made marriage less attainable and less required for poor and working-class Americans (Cherlin 2009; Ellwood and Jencks 2004; Wilcox, Wolfinger, and Stokes 2015; Wilson 1987). Nevertheless, this divide matters because children are, on average, more likely to thrive when they are raised in a stable, two-parent home. Compared to cohabitation, for instance, marriage in the United States is markedly more likely to bundle commitment, nonviolence, and stability (Kenney and McLanahan 2006; Musick and Michelmore 2018; Nock 1998; Wilcox and DeRose 2017). Figure 2.3, which displays the likelihood that children will see their parents break up before age 12 by parental education and marital status, shows a big gap between cohabiting and married parents (Wilcox and DeRose 2017). Other research indicates that children born to cohabiting couples who never marry are almost twice as likely to see their parents break up, compared to children whose parents are married, even after controlling for a range of confounding factors, such as parental education, race, and income (Musick and Michelmore 2018).

There are many reasons why children raised by married parents are more likely to flourish compared to children raised in single-parent families. For example, children in married-parent families have access to higher levels of income and assets, more involvement by fathers, better physical and mental health among both parents, more family stability, and many other factors (Ribar 2015). Most of these individual factors have been shown to have a positive impact on children’s well-being. David Ribar’s recent study of the impacts of marriage on children investigated the effects of these specific mechanisms. Even after accounting for these factors that are correlated with marriage, he finds that children with married parents have better outcomes. This means that, even given equal levels of parental attention, income, family stability, and other factors, children in married-parent families tend to end up better off than those living in other types of family arrangements. The advantages of being raised in a married-parent family appear to be more than the sum of the inputs. As Ribar concludes, “The advantages of marriage for children’s wellbeing are likely to be hard to replicate through policy interventions other than those that bolster marriage itself” (Ribar 2015, 11).

We will not attempt to summarize the voluminous literature on family structure and child well-being, but outcomes related to education, economic security, and health suggest links between stable families and children’s well-being. For example, children raised in stable, married-parent families are more likely to excel in school, and generally earn higher grade point averages (Harker 2007). The effects of family structure are even stronger for social and behavioral outcomes related to schooling, such as school suspensions, whether a school contacts parents about a child’s behavior, and whether a child drops out of high school (Autor et al. 2016; Kearney and Levine 2017; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994). Children who live in homes with married parents are more likely to attend and graduate from college (Kearney and Levine 2017; Lerman and Wilcox 2014). Research from Melissa Kearney and Phillip Levine indicates that the effects of marriage on high school and college completion are larger for children from less-educated homes than for children from homes with college-educated parents (Kearney and Levine 2017). In other words, children are more likely to acquire the human capital they need to later flourish in adulthood when they are raised in stable, married-parent families. We note that the effects of family structure vary by outcome, race, and financial status. Some of the effects of family structure are modest, such as on academic test scores; other effects of family structure seem larger, such as high school graduation rates (McLanahan, Tach, and Schneider 2013).

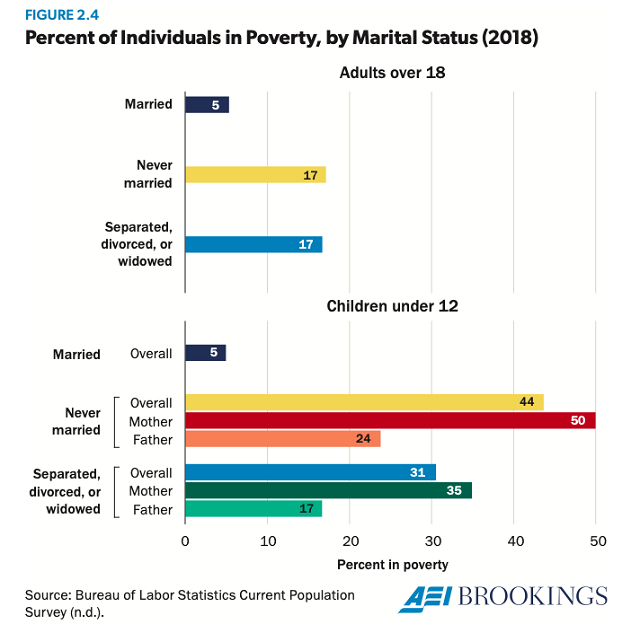

Because families that have two parents are more likely to have two earners, children in stable, married-parent families enjoy markedly higher income and lower risks of poverty and material deprivation (Lerman, Price, and Wilcox 2017). Figure 2.4 shows that children under age 12 living in single-parent homes are much more likely to be in poverty than children in married-parent families. Child poverty would be markedly reduced if the marriage rate was the same as it was in 1970 (Lerman 1996; Thomas and Sawhill 2005).

Obviously, much of the association between family structure and family income is about selection: married parents tend to be better educated and to be employed in better-paying jobs, even before they marry (Cherlin 2018). But part of the employment effect seems to be causal, as well. That is, marriage increases the odds that families have access to two earners, reduces the odds that households go through costly family transitions such as a divorce, engenders more support from kin, and fosters habits of financial prudence, including more savings (Eggebeen 2005; Lerman 2002).

The links between family structure and children’s economic well-being also extend over the life course. A recent study by Richard Reeves and Chris Pulliam found that upward economic mobility is much higher for the children of married parents. Among those who were in the bottom income quintile as children, four out of five who were raised by married parents throughout their childhood rose out of the bottom quintile when they reached adulthood. In contrast, those raised by a single parent throughout childhood had a 50 percent chance of remaining in the bottom income quintile (Reeves and Pulliam 2020). Another study, this one by Raj Chetty and coauthors, found sharp differences in upward mobility across geographic areas (Chetty et al. 2014); the strongest single predictor of rates of upward mobility in a particular area was the share of single-parent families. This factor was much more predictive than other measures tied to economic well-being, such as parents’ education levels, income, or race. To be sure, these studies report correlations and do not necessarily reflect the causal impact of marriage. But study after study shows a strong correlation between marriage and a wide array of positive outcomes, and also shows that the benefits of marriage are larger than would be predicted by economic factors alone.

Furthermore, regarding race, family structure can have a larger effect on some outcomes for white children than for Black children (Dunifon and Kowaleski-Jones 2002; Manning and Brown 2006). This differential impact across races and ethnicities may reflect greater support from kin or community organizations, such as churches, for Black and Hispanic children when they experience adversity related to family instability (Brown 2010; Putnam 2015). On the other hand, Black children are more likely to face other challenges, such as poverty, that compound disadvantages and increase the relative impact of family instability for them (Iceland 2019).

We also acknowledge that the quality of family life is crucial for the well-being of children, and not just the structure and stability of their family lives. Children do better when they receive high levels of affection, attention, and consistent discipline from their parents (Baumrind 2012). By contrast, children exposed to authoritarian and abusive parenting, or to high levels of conflict between their parents, are more likely to suffer, regardless of their family structure (Morrison and Coiro 1999). Indeed, the evidence suggests that parental separation is better for children in cases where high levels of conflict characterize a marriage (Amato and Booth 2000; Jekielek 1998). On the other hand, divorces involving children when there are low levels of conflict—perhaps one parent is depressed, the parents have grown apart, or one of the parents has had an affair—are more likely to make children worse off (Amato and Booth 2000).

Policy Priorities

After decades of decline, the share of children today being raised by married parents has stabilized and recently increased slightly. That’s the good news. The bad news is that a large share of children do not have married parents—especially those from lower-income backgrounds and Black and Hispanic children. To bridge this divide and to strengthen family environments for all children, we propose the following public policy and civic measures to strengthen and stabilize marriage and family life in the United States.

Reduce Marriage Penalties in Means-Tested Programs

Currently, means-tested programs such as Medicaid, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) penalize low-income couples who choose to marry (Carasso and Steuerle 2005) including working-class Americans, with one study showing that more than 70 percent of American families with young children and incomes in the second and third income quintiles face marriage penalties related to Medicaid, cash welfare, or SNAP receipt (Wilcox, Gersten, and Regier 2020; Wilcox, Price, and Rachidi 2016). These penalties can reduce the odds that lower-income couples will marry; one survey found that almost one-third of Americans ages 18 to 60 report they personally know someone who has not married for fear of losing means-tested benefits (Wilcox, Gersten, and Regier 2020; Wilcox, Price, and Rachidi 2016).

We recommend that Congress consider minimizing marriage penalties by (a) increasing thresholds for means-tested programs for married-parent families, especially those with young children; (b) experimenting with waivers that would allow state and local governments to try innovative approaches to reducing marriage penalties; or (c) passing a secondary earner deduction for low- to moderate-income families that would ease the financial impact of such penalties for two-earner families (Kearney and Turner 2013).

Strengthen Career and Technical Education and Apprenticeships

One reason marriage is fragile in many poor and working-class communities is that job stability and income are inadequate, especially for workers without a college degree. We acknowledge that better jobs and greater income are not a silver bullet. New research finds, for example, that better-paying jobs associated with fracking did not boost the share of children being raised in married-parent families (Kearney and Wilson 2018). But insofar as stable, decent-paying jobs remain a key ingredient for young adults considering marriage, steps should be taken to scale up vocational education and apprenticeship programs (Cass 2018; Lerman 2014; Sawhill 2018). We endorse recent initiatives to increase apprenticeships and shorter training programs. Congress should do more to expand access to apprenticeships and career and technical education and to support students in the completion of their degrees.

Encourage Young Adults to be Prepared before Having Children

Social marketing and relationship education on behalf of marriage could also prove helpful. Campaigns against smoking and teenage pregnancy have taught us that sustained efforts to change behavior can work. We would like to see a civic campaign organized around what Brookings Institution scholars Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill have called the success sequence, in which young adults are encouraged to pursue education, work, marriage, and parenthood, in that order (Haskins and Sawhill 2009; see also Wilcox and Wang 2017). Today, 97 percent of young adults who follow this sequence are not poor in midlife (Wilcox and Wang 2017). While the sequence has not been proven to exercise a casual role in adults’ economic lives, an extensive body of research indicates that each step—that is, education, work, and marriage—is associated with better economic outcomes for families with children (Lerman and Wilcox 2014; Wang and Wilcox 2020).

A campaign organized around this sequence—with hopefully widespread support from educational, civic, media, pop cultural, and religious institutions—might meet with the same level of success as the recent campaign to prevent teen pregnancy, a campaign that helped drive down the teen pregnancy rate by more than 65 percent since the 1990s (CDC 2015, 2016, 2017; Kearney and Levine 2014). All aspects of society should encourage young adults to plan and be mentally, financially, and relationally prepared for parenthood before starting a family.

1. It is convention to refer to the characteristics of the mother when describing the attributes of parents. These analyses would not meaningfully differ if we were to refer to fathers.