Highlights

On February 11, W. Bradford Wilcox testified before the Subcommittee on Human Resources, part of the House Committee on Ways and Means, about how the retreat from marriage contributes to the challenges low-income families face in today’s economy. This is the text of his testimony.

Chairman Boustany, Vice Chair Doggett, and other distinguished members of the Subcommittee on Human Resources, thank you for inviting me to participate in today’s hearing, “Challenges Facing Low-Income Individuals and Families in Today’s Economy.” This is a topic on which I have focused my scholarship in recent years and is a central focus of my recent research at the American Enterprise Institute and the Institute for Family Studies.

I. Introduction

This hearing focuses on the challenges facing lower-income individuals and families in today’s economy. As my testimony makes clear, I think economic factors—such as declines in the wages of non-college educated men—and social factors—for example, high levels of residential segregation by income and race—inhibit economic mobility, contribute to poverty, fuel economic inequality, and make family life challenging for lower-income Americans. The research also indicates that the nation’s retreat from marriage—marked by increases in non-marital childbearing, single parenthood, and family instability over the last four decades—is also inhibiting economic mobility, making poverty more common, and driving up inequality. Moreover, the retreat from marriage is concentrated among lower-income families. This means we are now witnessing a growing marriage divide where well-educated and affluent Americans enjoy comparatively stable, high-quality marriages, whereas other Americans are much less likely to enjoy such marriages. Thus, one major challenge facing lower-income men, women, and their children is that they are less likely to benefit from the social and economic advantages associated with growing up within or being a member of a stable, married family.

There are three points I will make today about this retreat from marriage in the United States:

1. First, in recent years, the retreat from marriage is concentrated among Americans who do not have college degrees. This means fewer lower-income Americans are living in stable, married homes.

2. This retreat from marriage makes poverty more common and income inequality more extreme than they would otherwise be, and it limits economic opportunity. Men, women, and children from lower-income communities are most affected by the social and economic consequences of this retreat.

3. The retreat from marriage is rooted in economic, policy, and cultural changes. Thus, public and private efforts to renew marriage and family life should be broadly gauged, seeking to strengthen the economic, policy, and cultural foundations of family life for the twenty-first century. Such efforts should focus on the families most affected by the retreat from marriage, namely, lower-income families.

II. The Retreat from Marriage and the Growing Marriage Divide in America

In recent years, the United States has witnessed a dramatic retreat from marriage that has had a disparate impact on lower-income Americans, in particular, and, more generally, among Americans who do not hold a college degree. Because education is a good proxy for social class, I rely upon adult educational attainment to explore how the retreat from marriage has affected less-educated Americans more than their college-educated peers. Among Americans without college degrees, the divorce rate is comparatively high, and non-marital childbearing, family instability, and single parenthood have been rising since the 1970s. By contrast, Americans with college degrees enjoy comparatively stable marriages and low rates of non-marital childbearing and single parenthood, and thus their children experience higher rates of family stability.1

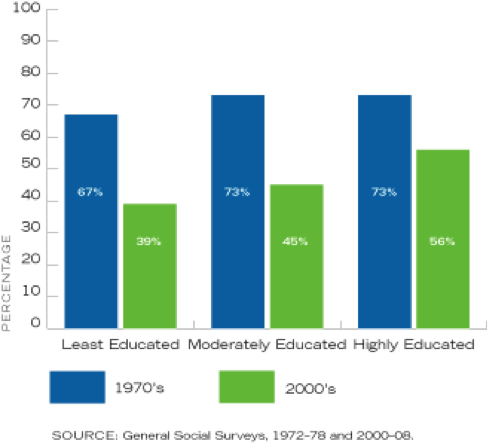

Take trends in adult marriage. Figure 1 indicates that stable marriage is now much less common among moderately educated men and women (i.e., those with a high school degree or some college) and men and women with the least education (i.e., high-school dropouts) than it is among those who are highly-educated (i.e., the college-educated). This means men, women, and children in lower-income communities are less likely to be living in stably married homes.

Figure 1: Percentage in Intact First Marriage, 25–60-year-olds, by Education and Decade

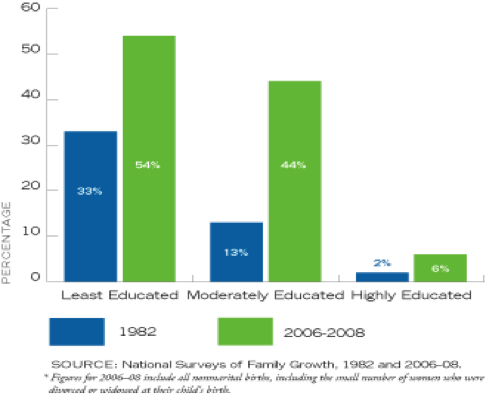

Or take trends in non-marital childbearing. In Figure 2, we can see that bearing a child out of wedlock is much more common among moderately educated women (i.e., high school or some college) and women with the least education (i.e., high-school dropouts) than it is among those who are highly-educated (i.e., the college-educated). This means that lower-income women are much more likely to have children outside of marriage than middle- and upper-income women.

Figure 2: Percentage of Births to Never-Married Women 15–44 Years Old, by Education and Year

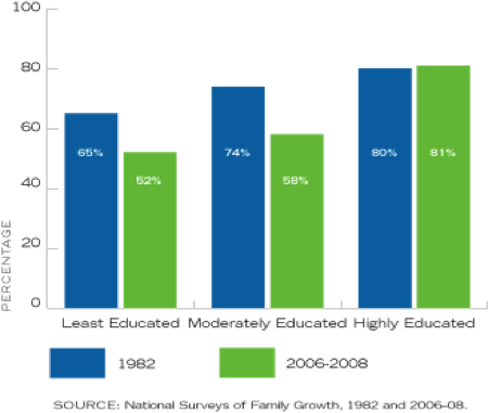

Trends in family instability for American teenagers also indicate that the retreat from marriage has had a disparate impact on the less educated. Figure 3 indicates that 14-year-old girls from less-educated homes are much less likely than those with college-educated parents to be living in a stable, two-parent home. This means that family instability is much more common today among lower-income families.

Figure 3: Percentage of 14-year-old Girls Living with Mother and Father, by Mother’s Education and Year

In sum, the United States is witnessing a retreat from marriage that reduces the odds that men, women, and children spend their lives in a stable, married home, a retreat that has hit less-educated and lower-income families with particular force.

III. The Consequences of the Retreat from Marriage

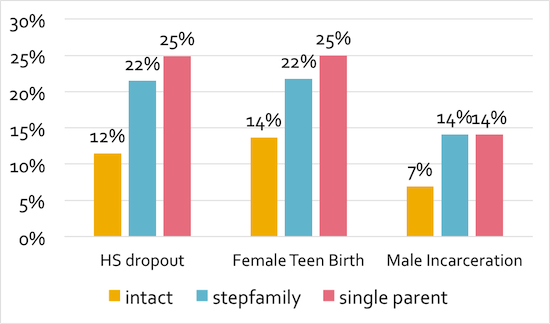

The retreat from marriage has had a number of important consequences for children, adults, and families in the United States. When children are raised outside of an intact, married family, they are less likely to acquire the human capital they need to thrive in today’s labor market; they are less likely to avoid major detours in young adulthood, such as incarceration or a teen pregnancy; and they are less likely to be working successfully as young adults. Specifically, Figure 4 shows that today’s young adults are more likely to do well in school, and to avoid a teen pregnancy or incarceration, if they grow up in an intact, two-parent family.

Figure 4: Young Adult Outcomes, by Family Structure Growing Up, Adjusting for Age, Race, Ethnicity, and Maternal Education (Source: NLSY97)

The retreat from marriage also has increased the odds that families are poor, both because single parents cannot pool income and assets with a second parent, and because unmarried fathers tend to work less and earn less than their married peers.2 A 2013 Census report found, for instance, that poverty rates are five times as high for children headed by a single female head of household (31 percent), as they are for children living in married-couple families (6 percent).3 Likewise, a recent American Enterprise Institute-Institute for Family Studies study finds that men work more hours and make more money if they are married rather than single; this is true even among men with a high school degree or less. Such men also worked more hours and made at least $17,000 more per year if they were married, compared to their single peers with a similar background. This same study found that women now face no marriage penalty in their individual income.4 Taken together, these findings suggest marriage provides financial advantages to the average American family.

Of course, one reason that poverty is more common among single parents than it is among married-couple families is that men and women who experience the stresses and disadvantages of poverty are less likely to get and stay married. That is, lower-income Americans are more likely to select into unstable family situations. Nevertheless, given the fact that this retreat from marriage is concentrated among less-educated and lower-income Americans, the nation now risks a cycle of economic disadvantage: individuals with limited education and weak economic prospects have children outside marriage; children raised outside two-parent families are less likely to complete college and flourish in the labor market; and the cycle continues. The research of Raj Chetty of Harvard University and his collaborators indicates a strong association between rates of upward mobility for poor children in our nation’s communities and family structure, with poor children in communities headed by large numbers of single parents much less likely to climb the economic ladder than poor children living in communities with large numbers of two-parent families. So, for instance, poor children raised in the Salt Lake City metro area—with large numbers of two-parent families in their community—are much more likely to experience rags-to-riches mobility than children from the Atlanta metro area—with large numbers of single-parent families in their community. More research is needed to understand the association between mobility and two-parent families, but the association is striking, and needs to be acknowledged by scholars and policymakers alike.5

More generally, the retreat from marriage is linked to important economy-wide consequences in the United States, namely, stagnant family incomes, family income inequality, and declining male labor force participation in the country as a whole. Specifically, Lerman and Wilcox (2014) estimate that “the growth in median income of families with children would be 44 percent higher if the United States enjoyed 1980 levels of married parenthood today. Further, at least 32 percent of the growth in family-income inequality since 1979 among families with children and 37 percent of the decline in men’s employment rates during that time can be linked to the decreasing number of Americans who form and maintain stable, married families.” To be clear: the retreat from marriage is not the only factor contributing to negative economic outcomes in the nation, but it is one important factor that must be addressed if the United States seeks to reduce poverty and economic inequality, and to increase the odds that every man, woman, and child has a shot at the American Dream.

IV. Why Marriage Is in Retreat

Progressive scholars have tended to argue the retreat from marriage and the growing class divide in marriage are rooted in structural changes in the economy, whereas conservative scholars have tended to point the finger at public policies and cultural trends they think have weakened marriage and the family. I think both sides are correct in this case.

For instance, sociologist William Julius Wilson has argued that the shift to a post-industrial economy has reduced the odds that less-educated men can find stable, good-paying jobs. This, in turn, reduces their ability to be breadwinners for their families, making them less “marriageable,” and reducing the odds that less-educated men (and their partners) get and stay married.6 Indeed, research suggests that economic changes—deindustrialization, the declining ratio of men’s to women’s income, etc.—have played a role in the retreat from marriage, especially among the less educated.7

But research focusing on economic factors can account for only a portion of the dramatic retreat from marriage.8 This means we must also look elsewhere to understand why marriage is in retreat, and why this retreat has been concentrated among lower-income families. When it comes to culture, the rise of expressive individualism, and the decline of a kind of marriage-centered familism, is certainly one factor accounting for the retreat from marriage in society as a whole.9 Furthermore, we now know that the decline of a marriage-centered life script, especially in connection with the bearing and rearing of children, has proved more common in poor and working-class communities than in college-educated communities.10 Means-tested transfer policies that both penalize marriage and make it less necessary for lower-income families undoubtedly have played some role in the retreat from marriage.11 As economists Adam Carasso and C. Eugene Steuerle point out, “most households with children who earn low or moderate incomes (say, under $40,000) are significantly penalized for getting married.”12 There is something, then, to conservative claims that welfare policies and cultural shifts may have undercut marriage, especially in lower-income communities.

To these standard accounts, I would add only one other major development. As political scientist Robert Putnam noted in Bowling Alone, Americans are now less civically engaged than they used to be, and declines in civic engagement have been concentrated among lower-income Americans.13 This is important because secular and especially religious civic institutions have historically supplied moral direction and social support to marriage and family life in the United States. All this means that a growing number of Americans, especially those without a college degree, do not possess the economic resources, the cultural commitments, and the civic ties that have long sustained a strong and stable middle-class family ethic in the nation.

V. Policy Recommendations

In summary, the nation’s retreat from marriage, a retreat that has been concentrated among the less educated, is one reason why poverty remains unacceptably high, economic inequality is on the rise, and the American Dream continues to prove so elusive to millions of men, women, and children across the nation. The growing marriage divide associated with this retreat from marriage is fueled by a range of economic, policy, cultural, and civic changes that have ended up jointly reinforcing the increases in non-marital childbearing, family instability, and single parenthood that lower-income communities have witnessed in recent decades. The concern here is that the United States is at risk of “devolving into a separate-and-unequal family regime, where the highly educated and the affluent enjoy strong and stable households and everyone else is consigned to increasingly unstable, unhappy, and unworkable ones.”14

To renew the fabric of marriage and family life, and to bridge the marriage divide, three sets of policies should be considered:15

1. First, public policy should “do no harm” when it comes to marriage. Accordingly, policymakers should eliminate or reduce marriage penalties embedded in many of the nation’s means-tested welfare policies designed to serve lower-income Americans and their families. One way to do this would be to use separate schedules for married couples and single individuals when it comes to determining eligibility for means-tested transfers. To reduce the cost of such a policy shift, the policy could be limited to the first five years of marriage, a period when couples are more likely to be bearing and rearing young children.

2. Second, public policy should strengthen the economic foundations of middle- and lower-income family life in three ways: (a) increase the child credit to $3,000 and extend it to both income and payroll taxes; (b) expand the maximum earned income tax credit (EITC) for single, childless adults to $1,000, with the intention of increasing their ties to the labor market and, hence, their marriageability; and (c) expand and improve vocational education and apprenticeship programs—such as Career Academies—that would strengthen the job prospects of less-educated young adults. The Career Academies model is particularly promising because the research indicates that young men who went through a Career Academy were more likely to flourish in the labor market and to get married than their peers from similar backgrounds.16

3. Third, federal and state governments—joined by a range of public and private partners, from businesses to public schools—should support a public campaign around a “success sequence” that would encourage young adults to sequence schooling, work, marriage, and parenthood in that order.17 This campaign—modeled upon the success the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy has achieved on the issue of teen pregnancy—would stress the ways children are more likely to flourish when they are born to married parents with a secure relational foundation. And, using the National Campaign as a model here, it would be better for this campaign to be directed and designed by a major nonprofit, rather than by the federal government.

I recognize that some of the policies that I have proposed today—such as the EITC expansion and the public campaign on behalf of a success sequence—are not yet proven. Given that, it might be wise to roll them out in a few states or municipalities, evaluate them, and see if they achieve their intended objectives. Indeed, a version of the EITC expansion is currently being tested right now in New York, NY. I also recognize that government’s role when it comes to strengthening marriage and family life is necessarily limited. Any successful twenty-first-century effort to renew the fortunes of marriage in America will depend more on civic institutions, businesses, and ordinary Americans than upon federal and state efforts to strengthen family life.

But given the toll that the nation’s retreat from marriage has taken on the social and economic welfare of lower-income families, the federal government should continue to experiment with a range of economic, educational, and cultural measures to strengthen family life and bridge the nation’s marriage divide. After all, the alternative to “seeking strategies like these is to accept a country where college-educated Americans enjoy stable and strong families; everyone else is consigned to increasingly unstable and fragile families; and high rates of economic inequality, male joblessness, and economic immobility are locked in by a marriage divide that puts working-class and poor Americans at a major family disadvantage.”18 I think we can all agree that such an alternative is unacceptable and un-American.

Thank you for this opportunity to testify.

Notes:

1. David T. Ellwood and Christopher Jencks, “The Uneven Spread of Single-Parent Families: What Do We Know? Where Do We Look for Answers?” in Social Inequality, ed. Kathryn Neckerman (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2004). W. Bradford Wilcox, When Marriage Disappears: The Retreat from Marriage in Middle America (Charlottesville, VA: National Marriage Project/Institute for American Values, 2010).

2. Lerman and Wilcox, For Richer For Poorer; Steven L. Nock, “The Consequences of Premarital Fatherhood,” American Sociological Review 63 (1998): 250-263.

3. Carmen DeNavas-Walt, Bernadette D. Proctor, and Jessica C. Smith, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2012 (Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, 2013).

4. Lerman and Wilcox, For Richer For Poorer.

5. Raj Chetty et. al., “Where is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States” (Cambridge, MA: The Equality of Opportunity Project, Harvard University, 2014).

6. William Julius Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, The Underclass, and Public Policy (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1987); William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (New York: Random House, Inc., 1996).

7. David T. Lichter et al., “Economic Restructuring and the Retreat from Marriage”, Social Science Research 31, no. 2 (2002): 230-256; Daniel T. Lichter et al., “Race and the Retreat From Marriage: A Shortage of Marriageable Men?” American Sociological Review 57, no. 6 (1992): 781-799.

8. David T. Lichter et al., “Economic Restructuring and the Retreat from Marriage”, Social Science Research 31, no. 2 (2002): 30-256”; Robert A. Moffitt, “Female Wages, Male Wages, and the Economic Model of Marriage: The Basic Evidence,” The Ties That Bind: Perspectives on Marriage and Cohabitation ed. Linda Waite and Elizabeth Thompson (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 2000), 302-319; Ellwood and Jencks, “The Uneven Spread of Single-Parent Families: What Do We Know? Where Do We Look for Answers?”

9. Andrew J. Cherlin, The Marriage-Go-Round (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009).

10. Kay Hymowitz, Marriage and Caste in America: Separate and Unequal Families in a Post-Marital Age (New York: Ivan R. Dee, 2007); Wilcox, When Marriage Disappears.

11. Amy C. Butler, “Welfare, Premarital Childbearing, and the Role of Normative Climate: 1968–1994,” Journal of Marriage and Family 64, no. 2 (2002): 295–313.

12. Adam Carasso and C. Eugene Steuerle, “The Hefty Penalty on Marriage Facing Many Households with Children,” Marriage and Child Wellbeing 15 (2005): 157–175.

13. Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000); Wilcox, When Marriage Disappears.

14. Wilcox, When Marriage Disappears, p. 53.

15. These recommendations are drawn, in part, from Lerman and Wilcox, For Richer For Poorer.

16. James J. Kemple, Career Academies: Long-Term Impacts on Work, Education, and Transitions to Adulthood (New York: MDRC, 2008).

17. Ron Haskins and Isabel V. Sawhill, Creating an Opportunity Society (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2009).

18. Lerman and Wilcox, For Richer for Poorer, p. 55.