Highlights

Amid what most U.S. citizens would describe as an especially hard week in June 2016, a glimmer of humanity eked through an onslaught of internet-based commentary in the shape of a discussion between a UK grandma and “Google.”

Evidently grateful for “the person at Google headquarters” who was providing results to her, the now-famous senior citizen included the words “please” and “thank you” in her queries. She believed that by “being polite and using her manners the search would be quicker.”

Ten years ago, my skeptic side would have smiled and wondered how much her results were exacerbated by the additional terms of politeness. After all, “please” and “thank you” can seriously upend a good algorithm, no? Today, however, our world is bursting with creative scientists wondering just how far our race can take artificial intelligence or knowledge-based economies, and to what end. Grandmothers minding their manners can hardly confound contemporary search engines.

Regardless of search engine development, there are still quality problems with information people are retrieving. Even if a user talks nicely to Google, they may unwittingly be thankful for questionable results. People use the results of internet-based queries as primary sources for psychosocial and medical information gathering (for example, see Cline & Haynes, 2001; Fiksdal, 2014). Unfortunately, research-based articles are not always represented as the top matching results, or display on first pages of popular search engines (for example, see Metzger, 2007).

Although social scientists may be committed to their areas of expertise by writing up their results for public access through professional topic-based blogs, gaps exist in practical knowledge about how to best optimize that information. There is a disconnect between how consumers enter search phrases, and the way social scientists currently construct their article/post “tags,” “categories,” or hand-selected “excerpts” when populating specific fields before deploying web-based content (for example, see Ludwig, et al, 2013).

These facts lead us to believe there is a need for studies on how to “connect” social science writers and their intended audiences. Little did I know that an article I wrote four years ago, entitled “Is Falling Out of Love the Deathblow to Your Marriage?” would provide my research team the opportunity to investigate how people specifically search for marriage advice.

So, just how DO people “talk” to Google about their relationships?

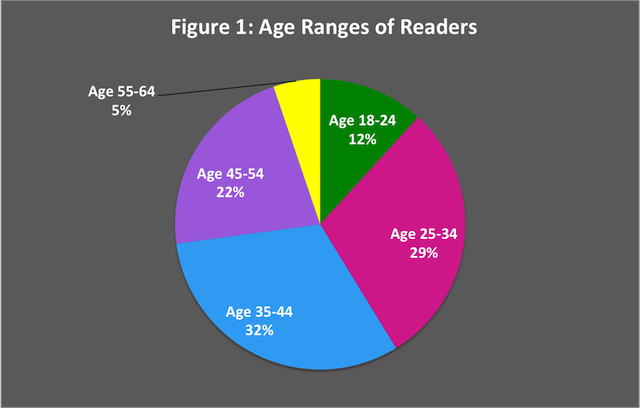

Google Analytics queries showed that since March of 2012, the link to my article had been clicked 81,000 times. Seventy-five percent were U.S. readers, and the remainder were mostly from Europe, then Asia. In terms of gender, 60.5 percent of readers were female and 39.5 percent were male. Average time spent on the page was a little over 2.5 minutes (for a breakdown of article readers by age, see Figure 1).

Because this was a “big data” question, we needed to select a sample containing the most viable information to study. Therefore, we limited the data set of search phrases leading to the article by only the dates when the link displayed on Google’s elusive “first page,” or about 18 months worth of results.

We assumed that people who were willing to dig further to read pages 2, 3 or 4 might be slightly different “searchers” than those grabbing what they quickly found on “Page One.” This reduced our sample to 5,136 lines of code. During Page One time, the article was being accessed between 50-150 times per day, as opposed to its ongoing performance to date of approximately 10-50 times per day.

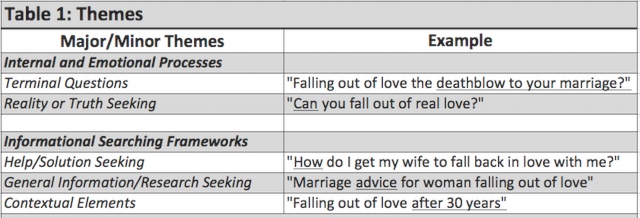

We cleaned the data, coded it qualitatively in several passes, and collaborated with professionals in the decision sciences. Our analysis resulted in a highly condensed summary of two major themes and five supporting minor themes.1 It was always our goal to produce not only useful but manageable information with this study, and we believe our interdisciplinary approach helped us hit that target.

Major and Minor Themes

The first major theme to emerge from our study was Internal and Emotional Processes, which involved users entering highly personalized phrases and “turning inward” in self-reflective ways. This is demonstrated by the two minor themes under this section: Terminal Questions, and Reality or Truth-Seeking.

Terminal Questions. Users entered phrases that seemed to be seeking answers about an end game. Many search phrases were constructed with questions about whether facts or behaviors meant a marriage or relationship was over. It’s common for people who are at a critical juncture in their marriage to wonder if they should continue to seek answers, look for some kind of release or relief, or face facts about the “death” of their relationship.

It seems the search for relationship truth isn’t limited to spirituality or philosophy, but also bleeds over into emotional relationship questions posed to “Dr. Google.”

Reality or Truth-Seeking Questions. Along these lines, but not exactly like terminally- focused questions, were “reality or truth-seeking” queries. This type encompassed the greatest percentage of all searches, with users wondering if mistrust can “cause a man to fall out of love,” or “is it possible to fall out of love then back into love.” In other words, the users were looking to normalize or validate their own experiences as well as get answers.

Of all the search phrases we coded, over 2,400 were presented by these two types (the first being a sub-type of the second), with 58 percent of those searching for factual, reality-based answers, and 42 percent wondering specifically if their relationship was over. It seems the search for relationship truth isn’t limited to spirituality or philosophy, but also bleeds over into emotional relationship questions posed to “Dr. Google.”

Information Searching Frameworks emerged as the second major theme. This conceptual area can be demonstrated by the following minor themes: help/solution seeking; general information and/or research seeking; and contextual elements.

In a DIY society, users frequently want to know the answer to: “How do I…?” We are also more conditioned to being an information-retrieving society as evidenced by the general or more specific topical searches such as “falling out of love,” or “true stories about falling back in love.” And many searches contained specific contextual information that further delineated that person’s experience, such as “falling out of love before the wedding,” or “falling out of love after kids.” Some context pieces were micro-specific, such as “falling out of love during cancer treatments,” or “falling out of love after 24 years of marriage.”

Table 1 offers a simple take on our results with underlining to demonstrate the focus of users’ searches:

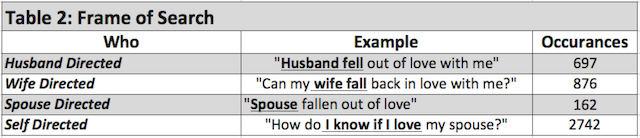

Perspective. Our team felt it was important to pass along two more lessons we learned. The first concerns the “perspective or frame of readers” as they sit at their computers or use their phones. If a user typed information about the focus of their search, we counted how that framing was positioned. Were people searching to learn about themselves or their spouses, or were they more generic in their research?

As noted earlier, the gender of our readers was tilted more toward females. However, Table 2 below shows that although most people were wondering about their own capacity or possibilities, more husbands specifically asked questions about their wives. But certainly, the key here is that the majority of “Google talks” are individually framed.

Micro-stories. Our final lesson is one that may be important for all social scientists writing web-based content in their respective fields. Approximately one of every 50 to 75 search phrases we examined from the full data set were what we began calling “micro-stories.” Here are a few examples:2

“husband and i in process of rekindling marriage after he shut down on me and had brief affair he still cannot make love fully or feel easy kissing why”

“separated wife and i when we see each other greet with a kiss on the lips this confuses me as we are separated and not working toward reconciliation”

“when her love is falling apart. when the one she knows is designed for her is broken? when they still love each other but can't show it? how do you fix it? how do you find it again? how do you rekindle it? how do you make it whole again?”

“specific words and body language that help make him listen and feel more attracted what to do if your man is distant and seems to have fallen out of love with you”

Although it might be easy for social scientists to stay focused on their narrow research agendas, we believe these micro-stories are valuable data that should be considered periodically as “windows into the world of Dr. Google, the Therapist.” There could be information in these micro-stories that provide insights to experts about unanswered questions, or evolving questions as society moves forward.

Especially salient lessons of these micro-stories are the way they are constructed. Google moved from “key word” search focus to “semantic search” technology for this very reason. Taking care to examine existing search data will help scientists understand how people form relationship questions, and reshape how they construct their excerpts, first paragraphs, tags, and headlines for their work.

Our research found that most people search like they talk, and, they “talk” to their search engines. If scientists are more thoughtful about how they write “answers” for users when communicating through “Dr. Google,” they are more likely to connect their hard work with those who need it.

Kelly Roberts, Ph.D., LMFT, is an assistant professor and the Director of the Office of Family Science in the Educational Psychology Department at the University of North Texas. Molly Weems is a graduate research assistant at the University of North Texas.

1. For a copy of this data set, or for questions, please contact Kelly Roberts, Ph.D., LMFT at the University of North Texas: kelly.roberts@unt.edu

2. Note: Micro stories are exact representations; they have not been modified for grammar or typeface.