Highlights

- In a country where generous maternity leave is rare, pandemic-related benefits and work changes created de facto baby bonuses and paid leave programs for a lot of (former) workers. Post This

- Big stimulus checks, paid time off work, and a shift toward a more family-friendly work culture combined to turn summer 2020 into a remarkable moment in American demography. Post This

- The baby boomlet we’re now seeing in hospitals across the country suggests pro-natal policy works. Post This

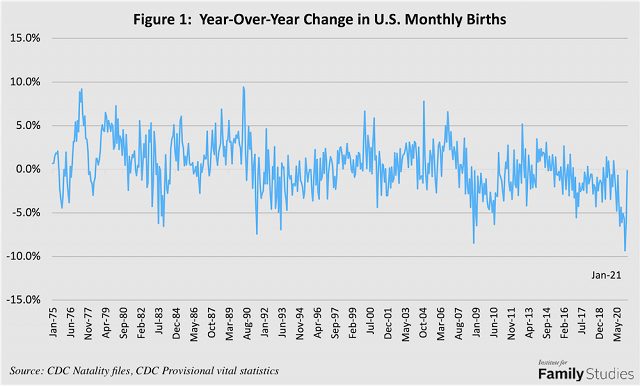

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a historic baby bust between November 2020 and February 2021, just as we predicted back in February of 2020. But many researchers, like the team at Brookings, predicted a more general, persistent decline in births in 2021, similar to what was observed after the 2008 recession. Data is now available to begin testing these theories, and indeed, births in January 2021 (nine months after April 2020) fell 9.3% around the U.S, according to new CDC provisional data. This is the largest year-over-year drop in decades, as Figure 1 shows.

But Figure 1 also shows something remarkable. By the last month of complete national data in March 2021, births had returned to their March 2020 levels. The sharp birth decline proved transient, unlike the decline in 2008-2009, which lasted for years.

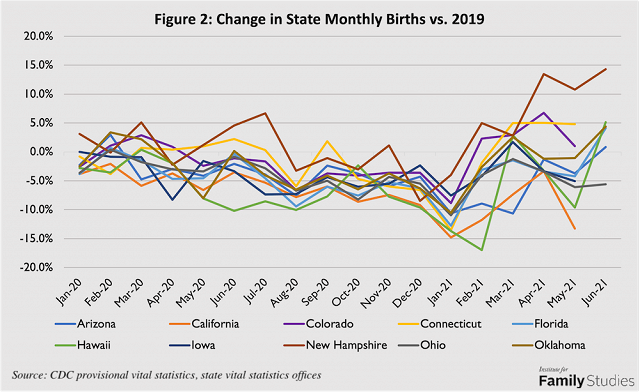

The CDC hasn’t released more recent data than March 2021, but some states have. Figure 2 below shows the change in births by month for states that have released data, compared to the same month in 2019. It also makes adjustments to reported birth data to account for delayed reporting in some states.

The specific details about how much various states are recovering are less important than the general trend: across numerous states, births are rebounding to nearly 2019 levels very quickly. Given that lockdowns and other policy measures, high unemployment, and excess deaths from COVID-19 persisted long past April 2020, and indeed to the present day, this is an astonishing outcome.

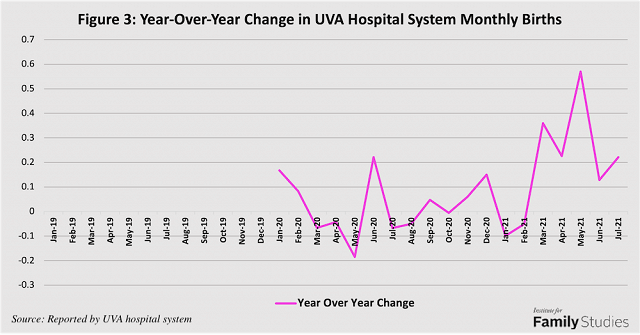

This trend shows up in other data, too. A study of pregnancies reported in electronic medical records in the University of Michigan’s hospital system found that pregnancies fell sharply during Michigan’s initial lockdown, but then rose above 2019 levels by late 2020. Births at the University of Virginia medical system confirm this trend as well. After declining sharply in January and February of 2021, they are now running 10-30% above the prior year’s level, as shown in Figure 3.

Conceptions plummeted during the lockdowns of March, April, and May, but as reopening began in June, conceptions rapidly normalized. Conventional stories about fertility don’t fit well here: employment was still extremely suppressed in the summer of 2020 and excess death rates were very high. It was not, in conventional terms, a good time to make a baby.

But there’s a plausible theory about why this birth rebound happened so fast. In this theory, the summer of 2020 was also a time when the country began to realize two key facts: first, that the pandemic was probably going to go on for a long time, with many, recurrent waves, and second, that some of the changes the pandemic brought were very helpful to families. Specifically, many people probably noticed that their bank accounts were doing all right, even if laid off, thanks to stimulus checks and generous unemployment benefits. These benefits created a unique opportunity for families to take a pause from working and have a long-delayed baby.

Moreover, as employers switched to remote work, and as remote work continued longer, more workers probably made a bet that remote work would last long enough to have a baby. In essence, in a country where generous maternity leave is rare, pandemic-related benefits and work changes created de facto baby bonuses and paid leave programs for a lot of (former) workers.

This theory has a lot of support. Academic research in other contexts has found that switches to remote work led to higher fertility. Copious prior research has found that child benefits (like the new expanded Child Tax Credit) and direct cash transfers (like the stimulus payments) boost fertility, if they’re big enough. Nor is this the first time that recession-fighting measures might have boosted births: when the UK arbitrarily slashed monthly mortgage payments for some families during the 2008 recession, those families’ fertility rates jumped upwards despite the ongoing recession.

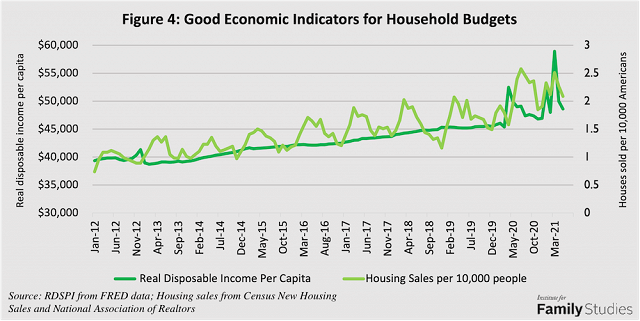

There’s more direct evidence as well. First, the financial transfers provided to families really were enormous, plenty large enough to matter. Figure 4 shows real disposable income per capita in the U.S. by month, as well as housing sales.

The first stimulus checks landed in American bank accounts in April and May, but it took until June and July 2020 for people to really feel flush and begin a huge house-buying spree. When the second and third stimulus rounds arrived (the two big spikes near the end), housing sales increased each time. It’s clear that stimulus payments pushed Americans’ incomes to unprecedented highs, and that high income fueled a binge of housing purchases: likely housing better able to accommodate growing families.

So the benefit scale is big enough to plausibly cause very real effects. That part of the theory checks out.

What about remote work?

A recent academic study surveyed workers from May to December 2020. Before COVID, less than 5% of workers were remote. But in those mid-2020 surveys, a full 20% of workers reported expecting to be remote at least through 2022. In other words, it really was in mid-2020 that expectations of long-term remote work leapt upwards.

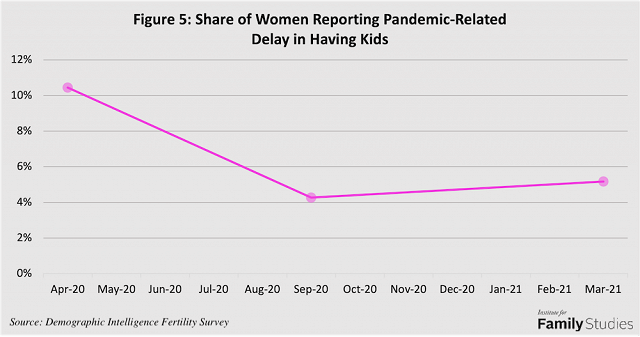

So on the stimulus and work side of things, the story checks out. But did fertility preferences actually change? Figure 5 shows the share of women ages 18-44 who said the pandemic had caused them to put off having a child, according to three surveys Demographic Intelligence ran in April 2020, September 2020, and March 2021.

Pandemic-related delays were very high in April 2020, but by September, they had fallen sharply. There really was a change in attitudes toward fertility during the summer of 2020. The same survey finds that in April 2021, the share of women who said their household’s financial situation had worsened was larger than the share reporting improvement, but by September, the two were balanced, and by March 2021 the net-improvers were the largest group. Highly-effective, stimulus stabilizing household budgets were a key driver of fertility normalization.

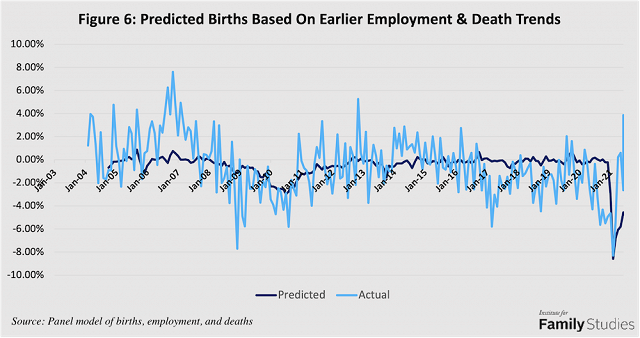

To formally test the theory that something unusual happened in the summer of 2020, we built a model identifying how changes in employment and death rates have historically impacted state level year-over-year changes in birth rates, basically using the year-over-year change in employment and death to predict the year-over-year change in births nine months later. Comparing the predicted average change in births across states to the actually observed change is informative. For April, May, and June of 2021, a limited number of states have released data.

The actual change in birth rates is much noisier than predicted by the model, but usually the predicted and actual birth changes trend together over time. However, beginning in April 2020, actual births fell far below what the model predicted. This is too soon for COVID to have been impacting conceptions. It’s possible that changes in abortion, miscarriage, immigration, or “birth tourism” could have driven this surprisingly rapid decline in births during the pandemic. Then in January 2021, nine months after the pandemic had begun in earnest, births plummeted. But by March, they were normalizing again, a trend that more-or-less continued in April, May, and June. So, what happened nine months before March 2021? Those babies would have been conceived right around May to July 2020, when stimulus checks had pushed incomes much higher, remote work was beginning to look more permanent, and Americans were buying new houses like crazy.

Big stimulus checks, paid time off work, and a shift toward a more family-friendly work culture (i.e., remote work) combined to turn the summer of 2020 into a remarkable moment in American demography. The upswing we’ve also seen in familism—the sense that families ground and guide our lives, especially in “difficult and dark times”—during the pandemic probably played a role as well.

So, despite huge social challenges and a raging pandemic, and despite school and child care closures making the job of parenting much harder, the straightforward remedies of giving families cash (per person in the household and especially per child), as well as nudging employers to provide more flexibility, seem to have helped lead to a rapid “normalization” of fertility. Policymakers should pay attention to this experience and learn a valuable lesson. The baby boomlet we’re now seeing in hospitals across the country suggests pro-natal policy works.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Brad Wilcox is Director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and a Senior Fellow of the Institute for Family Studies.