Highlights

- Parenting in the pandemic era had no shortage of challenges. That does not make the burgeoning narrative about a lack of child care pushing parents out of the workplace any more true. Post This

- Despite an aging population, the total number of women working is just about back to where it was in February 2020. Post This

- It seems likely that parents have shifted to embrace flex work and other hybrid arrangements as a result of the pandemic, allowing them to remain in the labor force while spending more time with their kids. Post This

In opinion pieces and think tank white papers, a post-Covid conventional wisdom has congealed. The post-Covid economy has pushed parents, especially mothers, out of the workforce because child care has become too expensive and too hard to find.

A recent Bloomberg Businessweek story typified the trend. Clare Suddath wrote about speaking to women who “decided to h*** with their college and graduate degrees, the years they’ve put into advancing their careers. They can’t afford to keep working.” She cites a U.S. Chamber of Commerce report that estimates one million women are “missing” from the labor force thanks to the impact of the pandemic. A Morning Consult survey found 31% of parents saying they had left or were going to leave the job market because of the cost of child care.

Everyone knows someone whose work-life situation was upended by the pandemic, so this kind of popular assessment might feel true. But on a macro level, it’s not, or at least not to any significant degree. One-third of parents quitting the labor force would have a seismic impact on the labor market data, yet nothing of the sort is visible to the naked eye. And unthinkingly repeating the idea that a million parents are being forced out of work, no matter how well intentioned, lends fuel to the cultural script that says America in 2022 is a uniquely toxic place to be a parent.

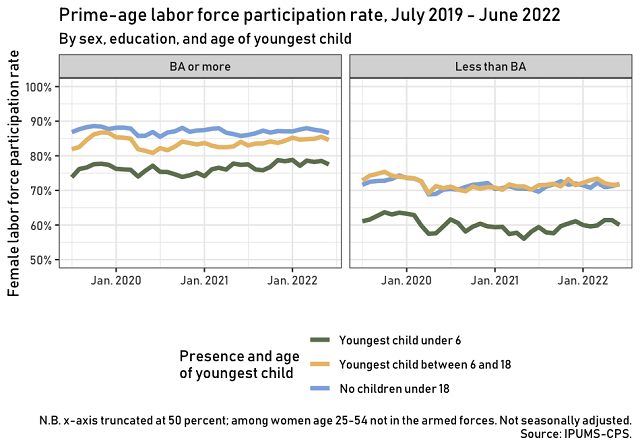

There are certainly individuals, like the ones Suddath talked to, who have been faced with painful trade-offs in this post-Covid world. But the share of college-educated women with young kids participating in the labor force (that is, working or looking for work) is now higher than it was pre-pandemic. Women out of the labor force were no more likely to be in their prime childbearing years than older women. Despite an aging population, the total number of women working is just about back to where it was in February 2020.

Even by last year, the employment-population ratio of mothers with very young children had rebounded: 59.4% of women with children under 3 were employed (about one-quarter of whom were working part-time.) That fraction, though slightly down from 2019, was higher than it was in 2018—far from evidence of a mass shift away from maternal employment.

The “one million missing moms” estimate Suddath cites is mostly an artifact of old data—she links to an April report from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce on female (not maternal) labor force participation, which in turn cites an NBC News write-up of a National Women’s Law Center factsheet relying on data from January 2022. It is true, as I previously covered for IFS, that the pandemic-related recession was unique in hitting women harder in its initial months. But by most of 2021—to say nothing of 2022—the gender imbalance had mostly righted itself. And many of the “missing” workers, a new NBER working paper suggests, weren’t parents without child care, but older workers choosing retirement.

Again, this is not to say that there aren’t some individuals, especially in high-cost areas of the country, that have decided it makes more financial sense to stay home with a child instead of find full-time child care. And the early months of the pandemic did indeed leave parents in the lurch. Every family with young kids knows someone with horror stories about classroom closures, skyrocketing prices, non-sensical mask rules, or other aspects of the post-Covid life we will be more than happy to put into the history books. (For my part, the three consecutive, two-week precautionary quarantines for preschoolers—with nary a positive test in the house—in Spring 2022 were my own personal breaking point.)

Parenting in the pandemic era had no shortage of inanities, difficulties, and real challenges. That does not make the burgeoning narrative about a lack of child care pushing parents out of the workplace any more true. Most parents are muddling through, taking advantage of a tight labor market, and bouncing back to pre-2020 levels of labor force participation. To the extent there is an ongoing effect, it appears to be concentrated among mothers without a college degree, though to what extent that reflects a shift in post-pandemic preferences isn’t discernable from the data alone. If parents were being forced out of the labor force due to child care constraints, we should be able to see it by more than just squinting at the data.

There is better evidence that the child care industry is under stress. The labor market that has been so good for workers has made it difficult for providers to hire and retain child care staff as workers have sought higher-paying jobs in other fields. As a paper by Chris Herbst and Jessica Brown (reader, I married her) found, child care has historically been slower to recover than other sectors of the economy. And at the same time, child care was difficult to find even before the pandemic, especially in high-cost urban areas.

If the child care industry is constrained, parents must be taking care of their child care in other ways, like relying on grandma or finding a home-based day care that’s a little less convenient. There are very good reasons to ease their burden through targeted policy interventions. The best way to solve the child care crunch is to boost provider capacity while strengthening parental choice, as Sen. Richard Burr and Tim Scott would do in their recent legislative proposal. States interested in giving parents more choices—including at-home care, faith-based centers, and home-based child care—could rethink the artificial distinction between pre-Kindergarten and child care, and experiment with models that embrace pluralism as a key concept. (The city of Boston has taken some steps along these lines.)

These types of approaches would have the virtue of expanding the choice set for parents without putting a heavy hand in favor of one type of care arrangement over any other. And they could easily be pursued at the local or state level, without needing to resort to despairing rhetoric to justify a massive federal legislative push.

There are certainly many ways we could make the United States a better place to raise a child. Some policies that could ease the burden on many parents might even get bipartisan support. But the cultural narrative that the economic, social, and cultural expectations are so crushing that parents must reorient their entire lives or give up their professional aspirations to have children need to be tempered with a dose of reality.

As Robert VerBruggen recently wrote for IFS, marriage and parenthood can change a lot about a couples’ outlook on life, work, and what is most important. It seems likely that parents have shifted to embrace flex work and other hybrid arrangements as a result of the pandemic, allowing them to remain in the labor force while spending more time with their kids in those early years. As America recovers from the pandemic, parents are making it work. In our efforts to make it easier for them, let’s not rush to paint apocalyptic pictures that far outstretch what the data tell us.

Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He writes from Columbia, S.C.