Highlights

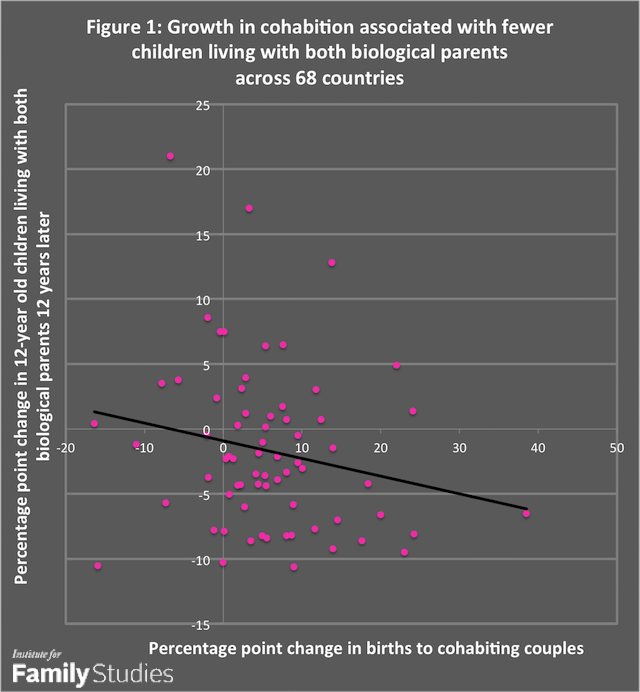

On Monday in this space, I described findings from the 2017 World Family Map report and included the scatter plot below showing how a rising share of births to cohabiting couples corresponds to a declining share of children later living with both biological parents.

Many were less than impressed because of the wide scatter of the points and the shallow slope of the trend line. This criticism is fair: the proportion of the variance in the change in children’s living arrangements explained by the rise in cohabiting births was only 4 percent. When I did a better job of adjusting for the fact that children’s living arrangements were measured at various ages (I added an age cubed term to the adjustment equation), it didn’t change the fact that little of the variance was explained.

One of the main reasons the two-way relationship is so weak is that the share of births to lone mothers is, of course, strongly associated with whether or not children live with both parents later on. Lone mothers can partner with the child’s father, but children have a far better chance of living with both parents if they start out that way. The two-way scatter plot doesn’t consider lone motherhood. Children also live apart from their parents for reasons other than union dissolution (e.g., labor migration among parents).

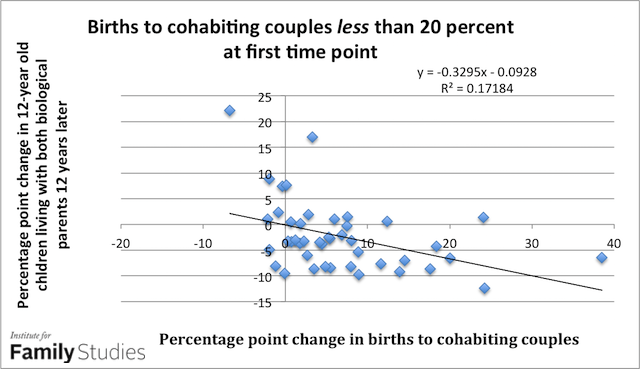

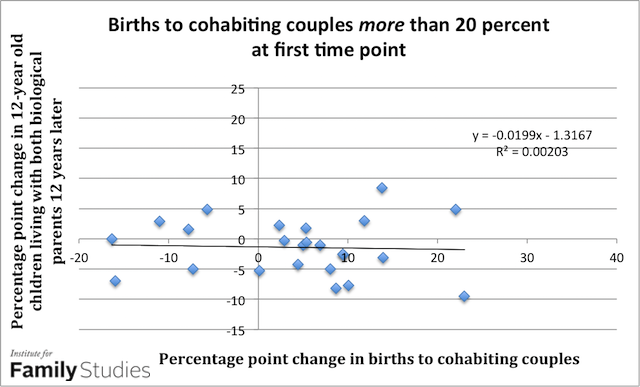

I’ve also discovered another important factor contributing to all the noise in the data: a rising share of cohabiting births doesn’t seem to matter much for children’s living arrangements where cohabiting births were already common as where they are beginning to become common.

Data for our first time-point come mostly from the 1990s. The countries starting out with a large share of cohabiting births are scattered throughout the world, but most of them (a dozen) are in Latin America and the Caribbean. There are also seven African countries in this group, plus three from Europe (France, Iceland, and Norway), and it is Mongolia that puts Asia on the list. Cohabiting births had risen to above 20 percent in many more European countries by the second measurement about a decade later.

Even the scatter plot indicating that the rise of cohabitation matters more in children’s lives earlier on in “the retreat from marriage” only explains 17 percent of the variation in children’s living arrangements. It nonetheless indicates that every percentage point rise in the share of births to cohabiting unions decreases the share of twelve-year-olds living with both biological parents 12 years later by 0.33 percentage points. Further, we know from the individual-level analysis of wealthy countries in the report that the stability gap between children born to cohabiting parents and children born to married parents has not gone away (nor is it systematically smaller) in countries with a high prevalence of cohabiting births.

Cohabitation clearly offers children more stability than lone motherhood. But even the relatively weak relationship we document indicates that it still is associated with family instability for children across the globe.