Highlights

- As more moderately inclined religion-goers leave their faith, religious life becomes increasingly defined by the most ardent and committed believers. Post This

- It's not just that young adults are less religious—America’s youngest and oldest adults inhabit entirely different religious worlds. Post This

- The most and least religiously active Americans now make up a majority of the public. Post This

The most important trend in American religion can be summarized in just two words: steady and uneven. For nearly the past three decades, national surveys have shown a consistent drop in religious affiliation, attendance, and even belief in God. At the same time, these same surveys show that this national decline varies dramatically by region, generation, and religious commitment.

Americans are inarguably more secular than they once were, but large numbers of Americans remain as staunchly committed to their faith and religious communities as ever. We are becoming a country with dueling religious experiences and perspectives—we are very religious and very secular.

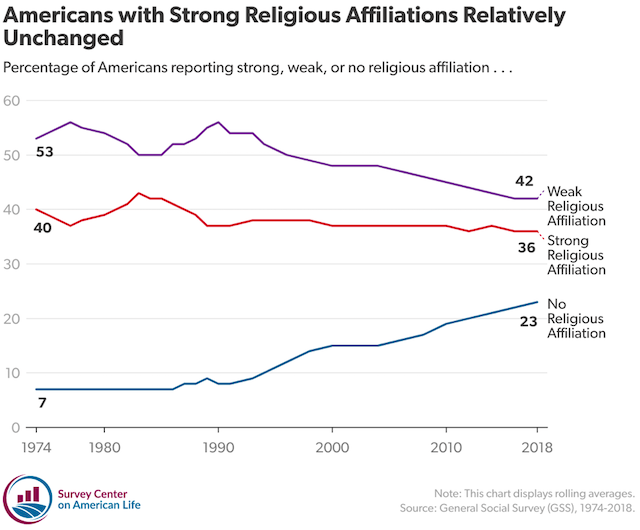

How has this happened? It’s a result of who is leaving. Surveys have long shown that the Americans who disaffiliated or left their faith are those with comparatively weak religious attachments. This has been true for about as long as we’ve been measuring religious change. In a 2017 paper, Landon Schabel and Sean Bock find that those with strong religious affiliations exhibited little change in identity. The authors argue:

If it is primarily … those with loose ties to their religions driving the decline in average American religiosity, then we may be seeing more of a polarization of religion than a pattern consistent with the secularization thesis ... Cultural divides could subsequently become even more pronounced, as there are fewer moderately religious people to bridge the divide between intense religionists and secularists.

Exactly right. As more moderately inclined religion-goers leave their faith, religious life becomes increasingly defined by the most ardent and committed believers. This then further alienates those on the fringe. (The chart below extends Schabel and Bock’s analysis showing the decline of Americans with weak affiliations.)

But this is not the only cause of America’s growing religious polarization.

Geography and Generation

The decline of religion in the US is a uniquely American story reflecting a distinctly national trend. But religious losses are geographically clustered. Not all states are experiencing the same degree of religious decline.

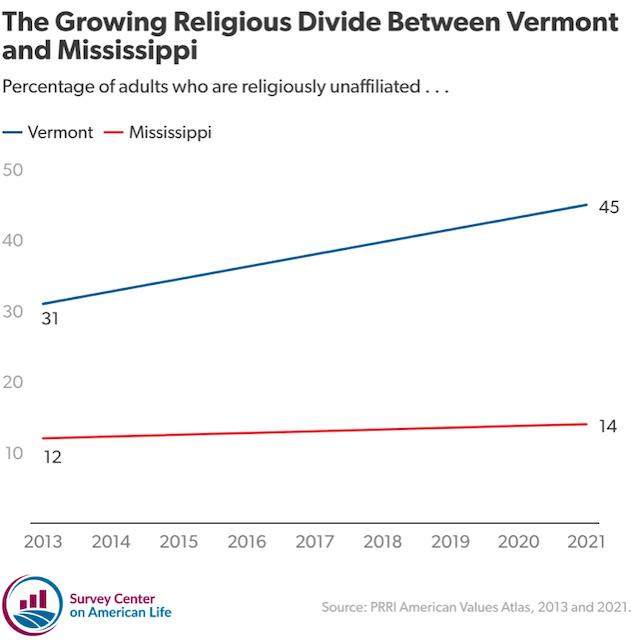

A 2017 Gallup analysis shows yawning state-level differences in religiosity, with Mississippi and Vermont representing the most and least religious states, respectively. Fifty-nine percent of Mississippians say religion is very important to them compared to only 21 percent of Vermonters. And the religious divide between these two states is growing larger. According to the American Values Atlas, the number of religiously unaffiliated Vermonters jumped to 45 percent from 31 percent in less than a decade. Meanwhile, in Mississippi the percentage of nonreligious residents barely budged, rising only two points. But this trend is not limited to these two states. A recent paper finds that, “steeper increases in the share of religious nones in states that had more nones to begin with.” In other words, the religious gap at the state level is growing wider.

Vermont and Mississippi have always had distinctive cultures, geographies, and histories. But until recently, both states were full of practicing Christians. This is far less true today. What’s more, these differences are reflected in the approach these two states have taken on issues of religious liberty, abortion, contraception, and LGBTQ rights. In 2016, Mississippi passed a “Religious Freedom” law that would, among other things, protect “state employees who refuse to license marriages, religious organizations who fire or discipline employees and individuals who decline to provide counseling or some medical services based on those oppositions.” In stark contrast, last fall Vermont became the first state to pass a constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to abortion and contraception.

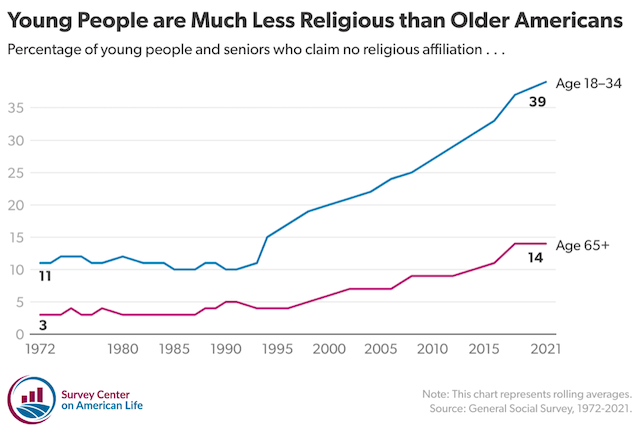

Religious changes have affected generations quite differently as well. Young adults are disaffiliating from religion at far greater rates today than they did a generation ago. The higher rates of disaffiliation among Gen Z and Millennials are largely the result of being raised in households that placed less emphasis on regular religious practice. Now, the age gap in religiosity has never been wider. According to the General Social Survey, 42 percent of young people are religiously unaffiliated compared to 17 percent of seniors, a whopping 25-point gap between the youngest and oldest Americans. In the early 1990s, there was only a six-point divide separating young adults and seniors.

It's not just that young adults are less religious—America’s youngest and oldest adults inhabit entirely different religious worlds. Young adults are coming of age at a time when religious leaders are far less trusted. Religiosity has become closely associated with conservative politics and anti-gay attitudes. Their social contexts are also distinct—young adults today are more likely to know an atheist than an evangelical Christian.

Rising Secular identity & Social Segregation

America’s religious polarization is not only the result of there being more nonreligious people, but that many nonreligious Americans have embraced distinctively secular worldviews. More than two decades ago, a pair of sociologists, Michael Hout and Claude Fischer, identified a growing number of people with no formal religious affiliation. However, their research showed that most still had religious and spiritual inclinations. In fact, these “unattached believers” shared many of the same beliefs as those still practicing and expressed mostly positive views about the presence of organized faith in American society.

If that was once true, it no longer appears to be the case. Nearly twenty years after Hout and Fischer published their pathbreaking study, a group of political scientists challenged the notion that nonreligious Americans maintained an affinity for religion even if they no longer identified with a tradition. In Secular Surge, David Campbell, Geoffrey Layman, and John Green found that many nonreligious Americans have a distinctive secular worldview that influences their approach to politics and beliefs about the role of religion in public life.

The secular worldview among the nonreligious identified by Campbell and his colleagues is increasingly reinforced by the people around them. Today, secular Americans are far more likely to be surrounded by people who share their religious identities. A 2020 study found that eight in ten secular Americans have at least one close contact in their life who is also secular, and a majority have two or more. But it's not only friendships; secular Americans are also marrying people whose religious beliefs match their own. A 2021 survey found that more than six in ten (62 percent) secular Americans have a spouse who is also not religious. This represents a profound break from the past.

These personal relationships are important because they inform and affirm secular beliefs and attitudes. Secular Americans with a greater abundance of secular friends and family express greater doubts about God, are more critical about religion’s place in American society, and have far more negative views about organized religion and religious people. Increasingly so—in 2008, 59 percent of secular Americans said religion causes more problems than it solves. That figure jumped to 69 percent in 2021.

The Pandemic Made Polarization Worse

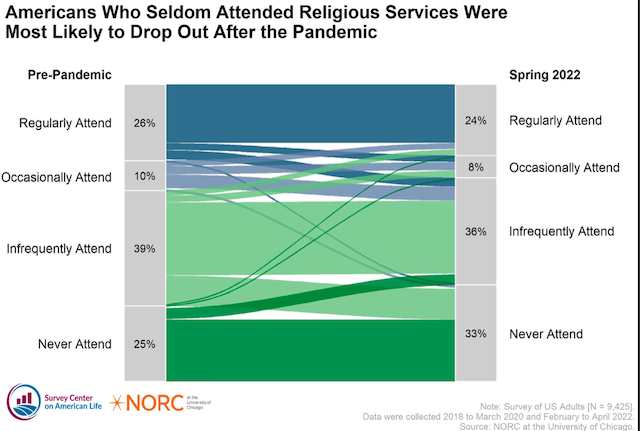

The pandemic did not fundamentally transform religious practice or belief so much as it accelerated existing trends. Our new study that interviewed people about their worship service attendance before the pandemic and again in spring 2022 found that more Americans now report that they never attend religious services. The study, coauthored with Jennifer Benz and Lindsey Witt-Swanson from NORC at the University of Chicago, found that not everyone was equally affected by the pandemic. The group most likely to have given up on church entirely were already infrequent participants.

As we state in the report, this may have made religious polarization worse:

Before the pandemic, roughly half of Americans were occasionally or infrequently attending services. Now, that number has dropped to about four in 10. Conversely, the percentage of Americans who never attend or attend at least weekly has increased.

One in four Americans participate in religious services regularly—attending roughly once a week or more—and one in three never go to church or worship at all. The most and least religiously active Americans now make up a majority of the public.

Despite this gloomy portrait, there is good news. Americans still broadly affirm the value of religious pluralism and the principle of religious liberty. America's growing religious diversity also serves as a challenge to this narrative of religious polarization. But our religious differences loom larger than they once did. Fortunately, America has had extensive experience navigating religious difference and overcoming religious prejudice. We are certainly capable of doing it again.

Daniel A. Cox is the director and founder of the Survey Center on American Life and a senior fellow in polling and public opinion at the American Enterprise Institute.

Editor's Note: This essay was first published in the author's newsletter, American Storylines. It has been republished here with permission.