Highlights

In my previous piece, I discussed the benefits of Canada’s Child Tax Benefit, the brainchild of the Family Caucus in the early 1990s. Could a similar program work well in the United States? Within the last year, groups across the political spectrum—from the liberal Center for American Progress and the Children’s Defense Fund to conservative policymakers such as Republican Senators Mike Lee and Marco Rubio—have put forward several proposals for child tax credit reform.1 Although all are noble efforts and promise to be pro-family, each has critical shortcomings that should worry those concerned with building strong families. Before extending support to any proposal, family advocates should examine whether it meets three requirements in regard to marriage, work, and family stability.

First, a reformed child tax credit (CTC) should be pro-marriage. One of the problems with the current tax/transfer system is that families are subject to marriage penalties under certain circumstances.2 This occurs when parents receive more benefits if they remain single (or cohabiting, as is often the case) than if they get married. Marriage penalties are most visible in income-tested programs where the infusion of income from a new spouse can lead the family to receive fewer benefits. For example, after a certain threshold, the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) or “food stamps” withdraws benefits at a rate of 30 percent for each new dollar earned. Such losses are significant disincentives for marriage among low-income families.

Second, the reform should be pro-work. The same dimensions of income-tested programs that discourage marriage can also discourage work. Parents find that income and payroll taxes combine with the withdrawal of benefits to create steep marginal tax rates, up to 80 percent in some cases, on any new dollar earned from working additional hours. Both the marriage and work penalties can be minimized or eliminated by moving away from income-testing to broadly universal programs.3

Lastly, CTC reform should contribute to family stability by consolidating the current array of benefits. Raising a family is hard enough today. Families should not have to navigate a maze of programs in order to maximize support for their children. Depending on their situation, parents may be eligible for SNAP, the child tax credit, the earned income tax credit, the dependent exemption, and the child and dependent care tax credit—each with its own eligibility standards and benefit rates. This not only creates unnecessary complexity but, as new research shows, also can be downright detrimental to family life by putting additional pressures on parents.4

For instance, consider a family experiencing job loss, and under immense economic and psychological pressures as a result—pressures linked to divorce and family instability.5 In addition to filing for unemployment or disability benefits to compensate for the loss of their paycheck and family tax benefits, parents must then take time away from their job search and family in order to apply to temporary food stamps for their children. The stigma is so great and the process so unpredictable that a large number of eligible families do not even bother to apply. As a result, many children are deprived of much-needed resources at a precarious time in their lives. Those who do receive benefits are tainted with the stigma of being “welfare children.” Part of the impetus for Canada’s reforms was a series of studies showing that children who received stigmatized welfare benefits did worse on a number of educational and emotional dimensions relative to similarly poor children not receiving welfare.6 To avoid this, the ideal CTC reform would take children off food stamps altogether without leaving them to go hungry.

Families should not have to navigate a maze of programs in order to maximize support for their children.

Unfortunately, none of the CTC reform proposals floating around the U.S. does anything to consolidate our maze of programs. Proposals to make the current CTC fully refundable in the absence of consolidation will only make marriage and work penalties worse. Proposals to introduce a new nonrefundable CTC will increase complexity and the debt burden on future generations while doing little for low- to moderate-income families. These are the same issues that the Family Caucus faced in Canada more than two decades ago. Their solution—consolidating a number of disparate tax/transfer programs into the refundable Child Tax Benefit—is a model for pro-family policymakers in the U.S. today.

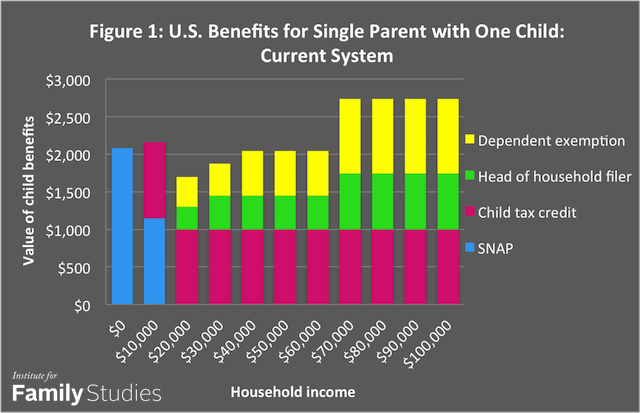

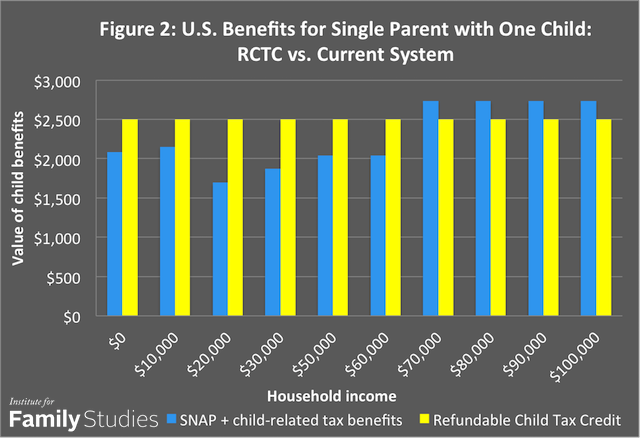

I would propose a radical reconstruction of tax/transfer benefits for families along those lines. Policymakers could consolidate the child tax credit, dependent exemption, child and dependent care tax credit, head of household filing status, and children’s portion of SNAP into one refundable child tax credit (RCTC) worth $2,500 per child. Like the current CTC, it would phase out after family income reached $110,000 at a rate of 5 percent for those filing jointly. The below figures depict the main benefits available to a single parent of one child today and compare the value of the RCTC to the value of the programs I believe it should replace.7 The RCTC would have several advantages over the today’s complicated tax/transfer system.

First, my proposal increases child benefits for almost all families, recognizing the importance of children and families in public policy. The Department of Agriculture estimates that it costs at least $9,130 per year to raise a child.8 Far from incentivizing childbearing, a $2,500 RCTC is only a small token of appreciation for the service performed by parents. Second, as a near universal benefit, it eliminates many of the marriage and work penalties found in the programs it would replace. Moreover, consolidation eliminates complexity so the benefits of marriage and work become more salient to parents. Third, it would enable families to make ends meet, even during unemployment spells, without applying for stigmatized welfare benefits. In effect, it takes children off food stamps.

Lastly, the RCTC would not necessarily balloon the deficit. Most of the cost of expanding the child tax credit and making it refundable would be offset by the elimination of other tax-transfer programs. Eliminating various loopholes in the tax code could certainly offset the remainder without raising income tax rates. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the cost of marriage penalty relief provisions in the 2004 tax legislation to amount to $114 billion. Most of this relief went to couples earning more than $75,000.9 Given the crisis of marriage among poor and working-class families, surely Congress could find the money to extend relief to the majority of parents making less than this.

Though it would not cure all that ails American families, meaningful child benefit reform based on the Canadian model would put the U.S. on the right track by eliminating many of the marriage and work penalties inherent in the current system while channeling more benefits to children in need. In sum, it is the fiscally responsible pro-family policy for which reform conservatives have been searching.

Josh McCabe is the Freedom Project Postdoctoral Fellow at Wellesley College, where his current research project looks at the politics and consequences of child-related tax credits in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom. Follow him on Twitter @JoshuaTMcCabe.

1. Center for American Progress (2015), Harnessing the Child Tax Credit as a Tool to Invest in the Next Generation; Children’s Defense Fund (2015), Ending Child Poverty Now; Marco Rubio (2015), Economic Growth and Family Tax Fairness Plan.

2. Carasso, A. and C.E. Steuerle (2005), “The Hefty Penalty on Marriage Facing Many Households with Children,” Future of Children 15(2): 157-175.

3. Ibid.

4. Levine, L. (2013), Ain’t No Trust: How Bosses, Boyfriends, and Bureaucrats Fail Low-Income Mothers and Why It Matters (Berkeley: University of California Press); Campbell, A.L. (2015), Trapped in America’s Safety Net: One Family’s Struggle (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

5. Charles, K. and M. Stephens (2004), “Job Displacement, Disability, and Divorce,” Journal of Labor Economics 22: 680-701; Conger, R. D. et al. (1990), “Linking Economic Hardship to Marital Quality and Instability,” Journal of Marriage and the Family 52: 643-656; Eliason, M. (2012), “Lost Jobs, Broken Marriages,” Journal of Population Economics 25: 1365-1397.

6. Ontario Social Assistance Review Committee (1988), Transitions: Report of the Social Assistance Review Committee (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer).

7. Assumptions for comparison of RCTC to current system of child-related benefits

My calculations are only a first estimate, and I encourage additional estimates for different situations. Depending on income, family structure, and use of childcare, benefits can vary quite a bit. For example, low- and moderate-income married families are likely to see bigger gains from my proposed reform relative to the current system, while some high-income families claiming the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) are likely to see losses under my proposal.

I chose to model changes for a low- to moderate-income single parent with one child not utilizing childcare eligible for the CDCTC. I chose these assumptions for several reasons including:

- Single parents are typically seen as more vulnerable.

- Single parents may be more concerned with the marriage and work penalties I discussed above.

- Child benefits in the tax/transfer system are more important to the economic wellbeing of low- and moderate-income families.

- It is not clear how many lower-income families actually utilize the CDCTC and nearly impossible for me to estimate its value without all sorts of additional assumptions.

- As a regressive tax measure, most of the benefits of the CDCTC accrue to families making $100,000.

Getting the numbers for each component

I simulated value of tax and transfer benefits at increments of $10,000 in annual income ranging from $0 to $100,000. I include Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, the current child tax credit, head of household filing status, and the dependent exemption because I am proposing to consolidate all of these into a single refundable child tax credit. (Even though I would include the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit in this consolidation, I have excluded it for the reasons discussed above.)

- SNAP: Benefits calculated using the North Dakota Department of Health SNAP Calculator found online at http://www.ndhealth.gov/dhs/foodstampcalculator.asp. I assumed a two-person household with only earned monthly income ($0, $833, $1,666) and rental costs equal to 30 percent of income.

- CTC: Benefit is equal to 15 percent of income over $3,000 up to $1,000 total.

- Head of Household Filer: I calculated benefit based on difference between this filing status and filing as single in order to isolate amount related to having children. In 2015, this amounts to $2,950 ($9,250 minus $6,300). Benefit is calculated after accounting for parent-portion of head of household filer status and standard deduction.

- Dependent Exemption: It is worth $4,000 in 2015. Benefit is calculated after accounting for head of household filer status and standard deduction.

8. United States Department of Agriculture (2014), Expenditure on Children by Families, 2013.

9. Carasso and Steuerle (2005).