Executive Summary

Fifty to 65% of Americans believe that living together before marriage will improve their odds of relationship success.1 Younger Americans are especially likely to believe in the beneficial effects of cohabitation, and to view living together as providing a valuable test of a relationship ahead of marriage.2 Yet living together before marriage has long been associated with a higher risk for divorce,3 contradicting the common belief that cohabitation will improve the odds of a marriage lasting.

This association between premarital cohabitation and divorce is often called the cohabitation effect. With 70% of couples living together before marriage,4 it is important to understand how and when cohabitation is associated with poorer odds of marital success.

Controversy over this topic has abounded, both in the media and in science journals, with some arguing that any association between premarital cohabitation and divorce is due to selection—that is, the association is merely related to differences in who does or does not live together before marriage—and others suggesting that something about the experience of living together makes a couple more likely to struggle in marriage. We believe both selection and experience are part of the explanation, and that there are steps people can take to increase their odds of having a lasting marriage based on how or if they cohabit before marriage.

Using a new national sample of Americans who married for the first time in the years 2010 to 2019, we examined the stability of these marriages as of 2022 based on whether or not, and when, people had lived together prior to marriage. Consistent with prior research, couples who cohabited before marriage were more likely to see their marriages end than those who did not cohabit before marriage.

The primary finding of this report is that the timing of moving in together is robustly associated with marital instability.

- Those who started cohabiting before being engaged were more likely to experience marital dissolution than those who only did so after being engaged or already being married.

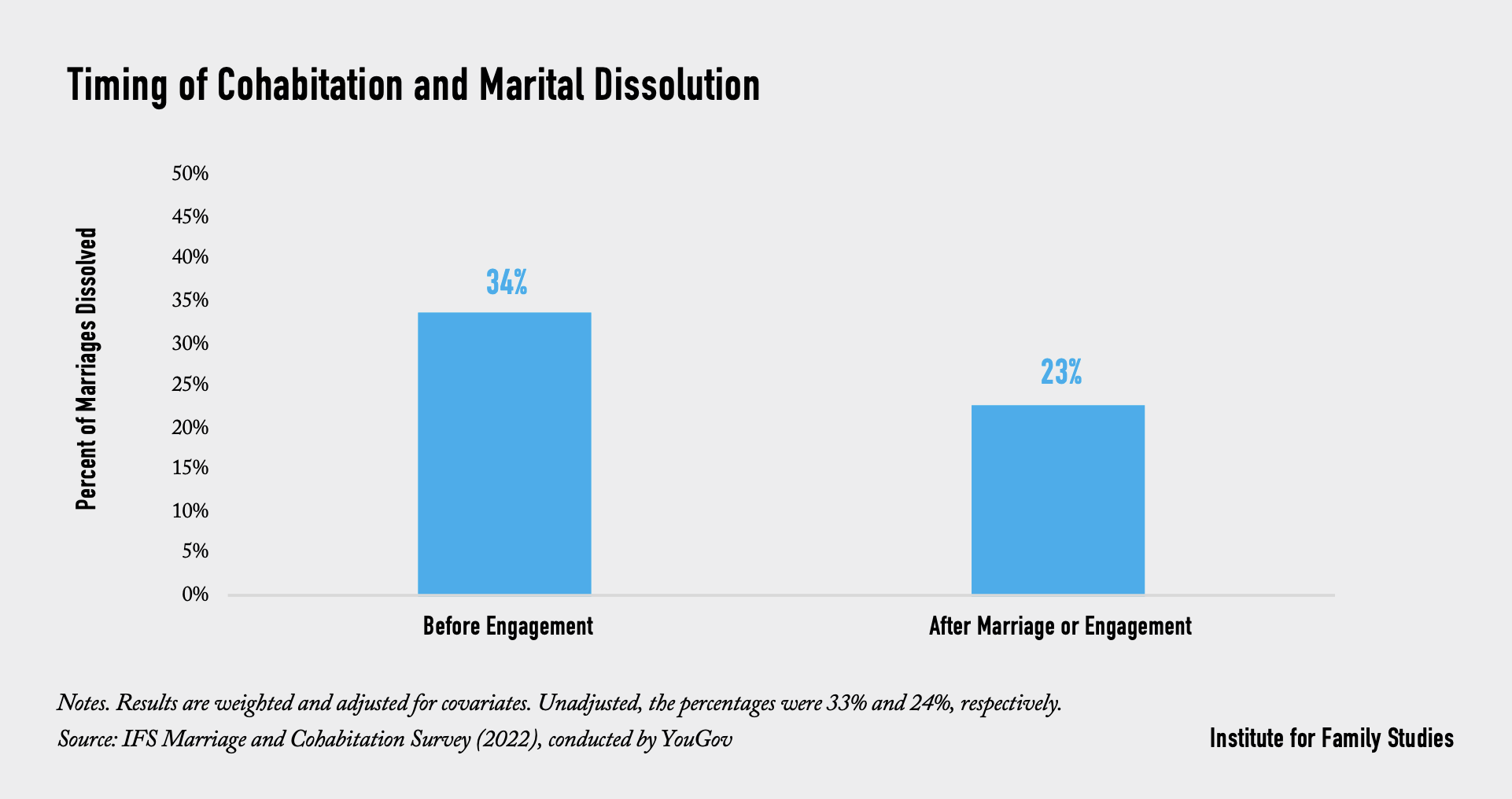

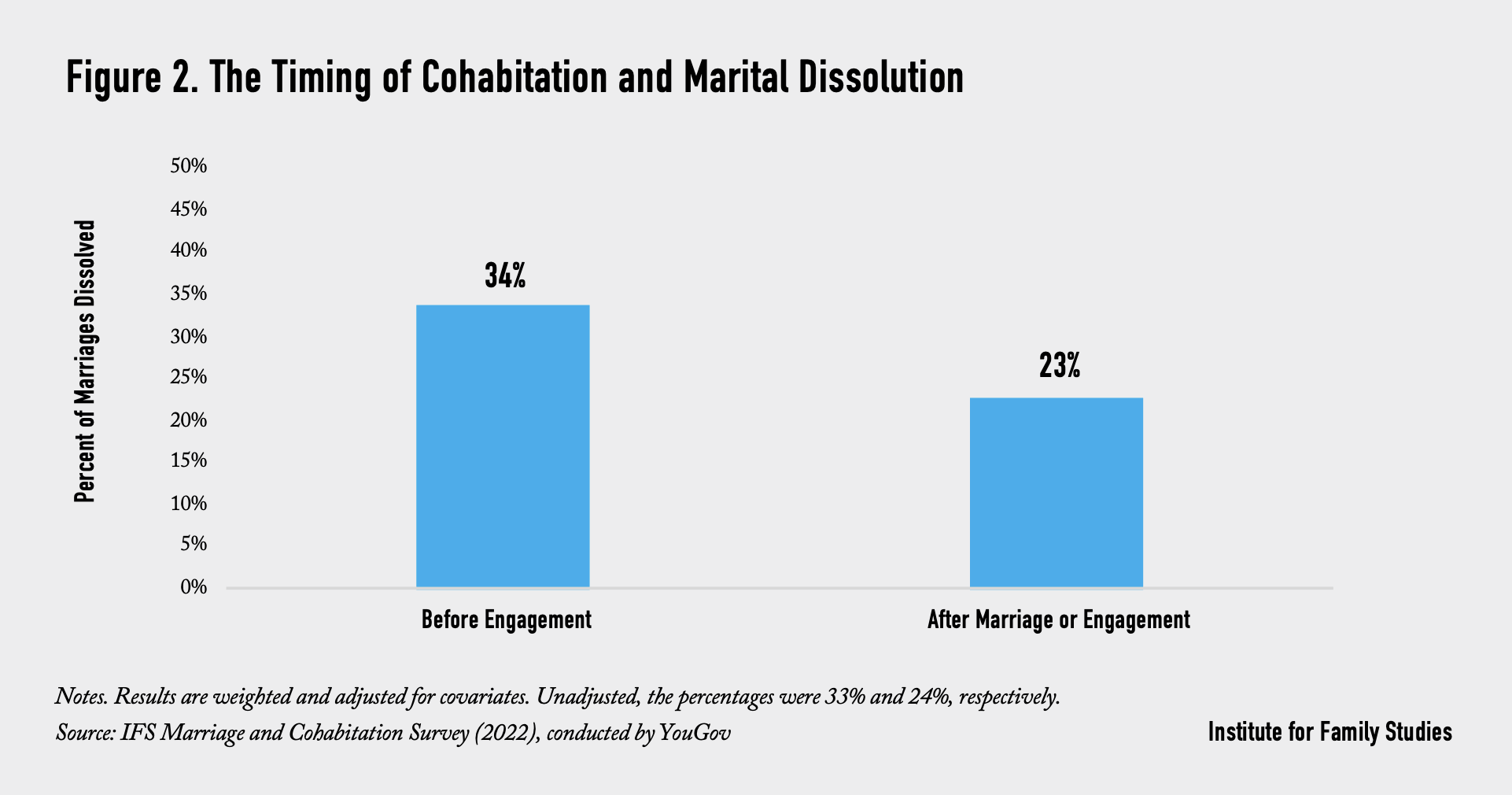

- Specifically, 34% of marriages ended among those who cohabited before being engaged, compared to 23% of marriages for those who lived together only after being either married or engaged to be married.

- In relative terms, the marriages of those who moved in together before being engaged were 48% more likely to end than the marriages of those who only cohabited after being engaged or already married.

Our findings suggest that one key to reducing the risk of divorce may be either not to cohabit before marriage or to have settled the big question about marital intentions before moving in together.

Key Takeaways

- Not living together before marriage, or only doing so after already being engaged to marry, is associated with a lower likelihood of marriages ending than living together before being engaged.

- Couples might lower their risks of divorce by having clear intentions to marry before moving in together or by waiting until marriage to live together.

- Reasons for moving in together also matter: People who reported that their top reason for moving in together was either to test the relationship or because it made sense financially were more likely to see their marriages end than those who did so because they wanted to spend more time with their partner.

- Having a greater number of prior cohabiting partners is associated with a higher likelihood of marriages ending.

- Talking about what living together means and making a decision together about it (rather than sliding into it) might help lower the risk of marital difficulties for some couples who will live together before marriage. Clarifying marital intentions may be a particularly important goal for such discussions.

About the Data and Methods

The data used for this study (N = 1,621) were collected by YouGov between July 28 and August 29, 2022. To participate in the study, respondents needed to be 50 years old or younger and to have married for the first time in the years 2010 through 2019, and to not be widowed from that spouse. They also needed to have married a partner who had not been married before and who also was 50 years or younger in age at the time of the survey. This is a U.S. sample.

All analyses in this study are based on weighted data. YouGov provided a weight to allow the sample to match the characteristics of the U.S. population on dimensions such as age, race/ethnicity, gender, education, and geographical region.

The analyses in the body of this report focus on whether marriages remained intact or dissolved. We define marital dissolution as divorce or separation, where the separation is likely permanent or likely to end in divorce. Thus, respondents’ first marriages were coded as ending if they reported they either had divorced, were separated for over a year, or were separated and considered their marriage to be over. In the sidebar on page 11, we present simple findings for the overall cohabitation effect (did or did not cohabit with spouse prior to marriage), showing both the pattern for divorce alone as the outcome or divorce and separation as defined above (dissolution).

All data in this report pertain only to marriages occurring in the U.S. in the years 2010 to 2019, with marital stability outcomes assessed as of 2022, but no later. Marital dissolution for still-married respondents that occurred after August 2022 is not captured.

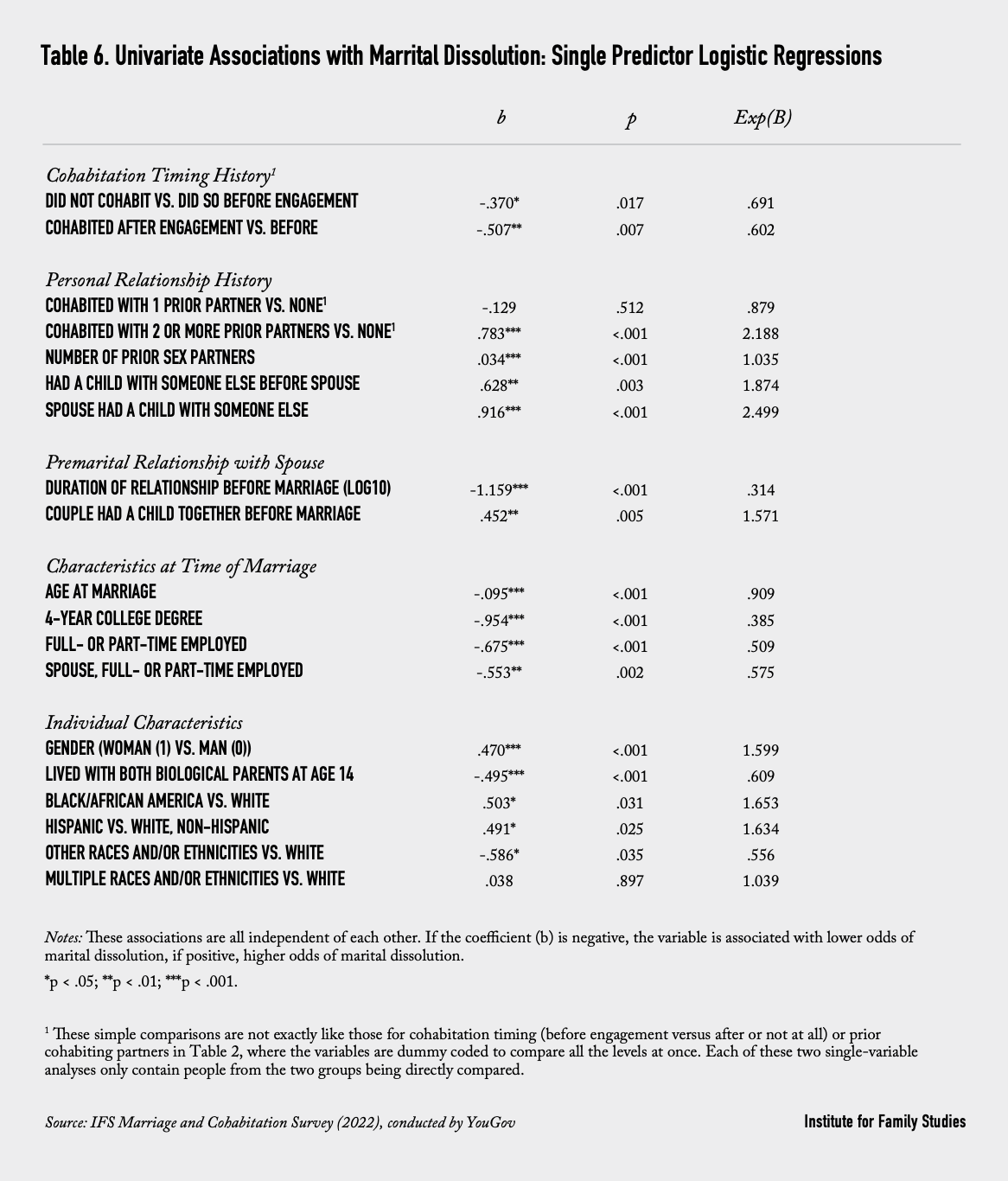

The primary analytic method was logistic regression, using various aspects of cohabitation history and numerous covariates as predictors of marital stability. The covariates included other variables that are often associated with whether or not couples cohabit before marriage and with the risk for divorce, in order to isolate the comparisons of most interest (used, therefore, as control variables for spurious associations): age at the time of marrying, education at the time of marrying, and employment at the time of marrying, along with gender, race, ethnicity, and variables associated with prior family or romantic relationship history. Such variables are often used to control for characteristics associated with selection.

For ease of interpretation, in the text we translate the odds ratios from logistic regression analyses into approximate percentages of marriages dissolved and percentage-point differences in the likelihood of dissolution for the groups being compared.

More detail on the sample, methods, and analyses are provided in the Appendix.

Introduction: The Cohabitation Effect

In the United States, cohabitation before marriage became increasingly common starting about five decades ago. This is one of a number of important changes in marriage and family since the 1960s.5 Back in the 1970s, researchers began wondering what living together before marriage might mean for whether a couple gets married or stays married.6 Cohabiting came to be seen as a way to lower one’s odds of divorce, perhaps partly in response to how divorce rates had climbed steadily from the late 1960s forward. By the late 1990s, more than three-fifths of high school students in the U.S. believed that “It is usually a good idea for a couple to live together before getting married in order to find out whether they really get along.”7 This sentiment remains just as popular now, with a majority of adults believing it is wise to live together first to test a relationship. And in practice, it is estimated that 70% of couples live together before getting married today.8

As cohabitation became popular, it changed from being mostly something couples might do before marrying to being a common relationship form, whether or not a couple was on a pathway to marriage. For a time, it was more of a stepping stone to marriage than it is now.9 In fact, over time, cohorts of cohabiting couples became increasingly likely to break up rather than marry, increasing the disconnection between cohabitation and marriage.10 As cohabitation has become more common, so has having a history of cohabiting with more than one partner, which is associated with reduced odds of ever marrying as well as increased odds of divorce.11 Although cohabiting has become less connected to marriage, it still precedes marriage for most couples who marry, which is why premarital cohabitation is our focus here.

Although many believe that living together before marriage will lower their odds of divorce, there is no evidence that this is generally true and a lot of evidence that it is not true. That is, for decades in the U.S., living together before marriage has been associated with greater odds of divorce and/or lower relationship quality in marriage, and not just in a few isolated studies.12 How can that be? Although cohabiting might help some people avoid a difficult marriage, the evidence from decades of research suggests it is associated with greater, not lower, risk of divorce. Two major categories of explanation have emerged to explain this perplexing set of findings: selection versus experience, which we will explain further here.

Selection. At least some of the association between premarital cohabitation and divorce is explained by selection— differences that already existed in people who cohabit before marriage.13 Selection plays an important role in this risk, regardless of all other factors.

Experience. Another explanation is that something about the experience of living together increases the risk for divorce.14 There are two different explanations in this category.

One explanation is that cohabitation changes how people think about marriage and divorce. The best example in this line of thought is research showing that having more experience over time with cohabitation before marriage decreases positive attitudes about marriage and increases comfort with divorce.15 In other words, the experience can change a person.

A second explanation is our theory of inertia. In physics, inertia refers to how much energy it will take to move an object or move it in a different direction than it’s already going. We apply this concept to cohabitation. Our theory is that moving in together can prematurely increase the inertia for remaining together prior to a couple making a clear commitment to a future in marriage. In other words, the inertia caused by moving in together will create resistance to someone moving back out.

Supporting this point, we have shown that moving in together increases various types of constraints on remaining together while not doing anything to increase commitment to a future together.16 In other words, cohabitation makes it harder to break up. That fact makes the timing of cohabitation relative to clarity about marital intentions important. Thus, we predicted over 20 years ago that timing and sequence about commitment and cohabitation would matter.17 That means that the risk for divorce associated with living together before marriage should be greatest for those who started living together before they had developed clear and mutually agreed upon plans to marry.

One of the clearest indicators of having mutual and clear plans to marry is engagement. Those who move in together after getting married or after being engaged have settled a big question about the path they are on prior to moving in together, while those who move in together before clearly settling marital intentions risk getting stuck or losing other opportunities to choose a spouse. In this theory, timing and sequence matter. In the words of another scholar, the risk for couples is becoming “prematurely entangled.”18

Findings

I. Timing of Premarital Cohabitation and the Risk for Marital Dissolution

In line with what the inertia hypothesis predicts, using this new data set, we created three groups of participants based on their cohabitation history: 1) Those who didn’t live with their spouse at all before marriage, 2) Those who lived together, but only after they had become engaged, and 3) Those who lived together before being engaged to marry. These groups were based on the following two questions:

1. Did you and your spouse live together before marriage? That is, did you share a single address without either of you having a separate place?

If a respondent answered yes to the above question, they were asked the following question to determine if they were cohabiting before or after engagement.

2) Had the two of you already made a specific commitment to marry when you first moved in together?

___ Yes, we were engaged.

___ Yes, we were planning marriage, but were not engaged.

___ No.

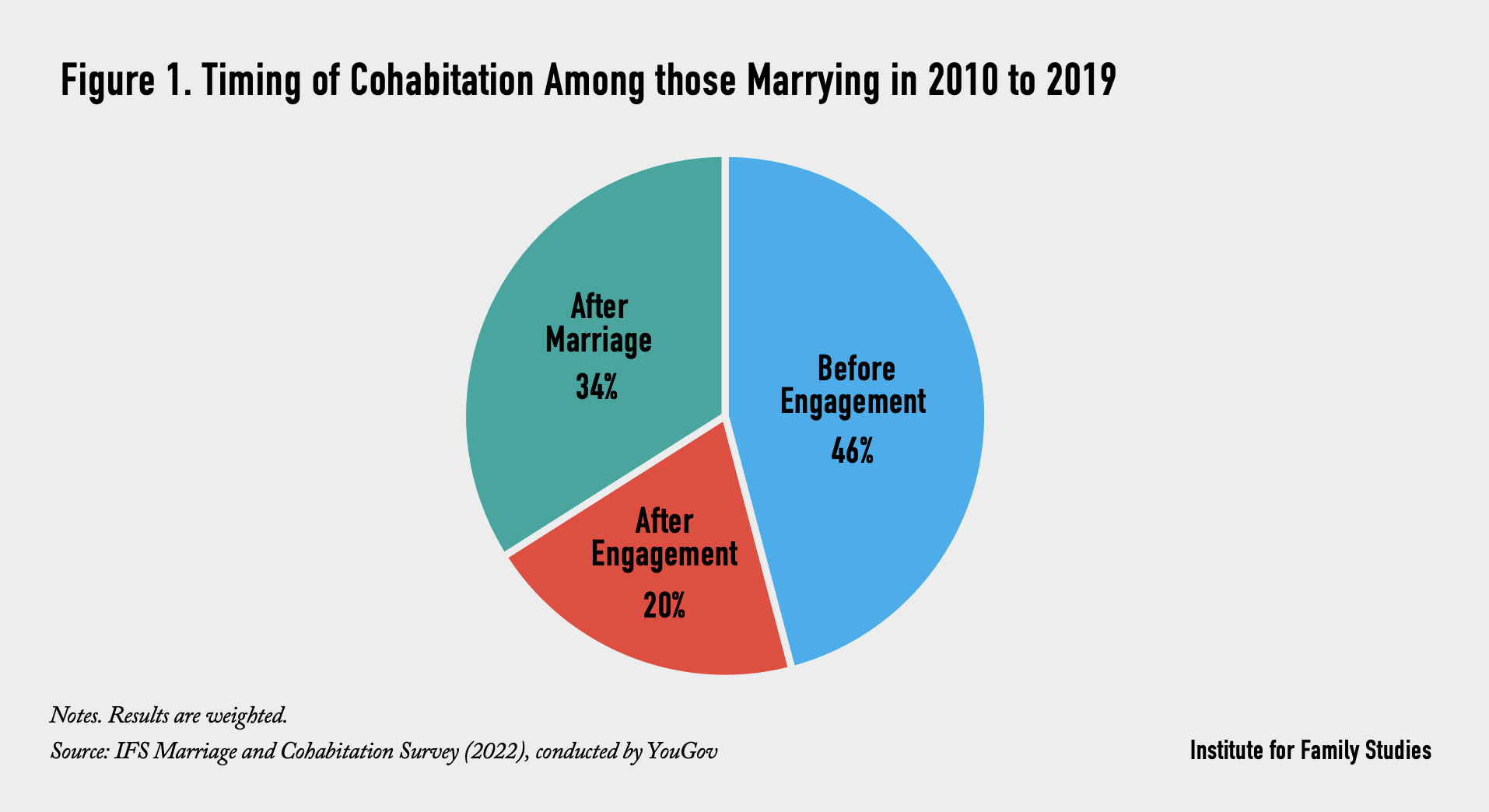

Figure 1 shows the percentages of those in our sample who lived together before engagement, after engagement, or did not cohabit with their spouse prior to marriage.

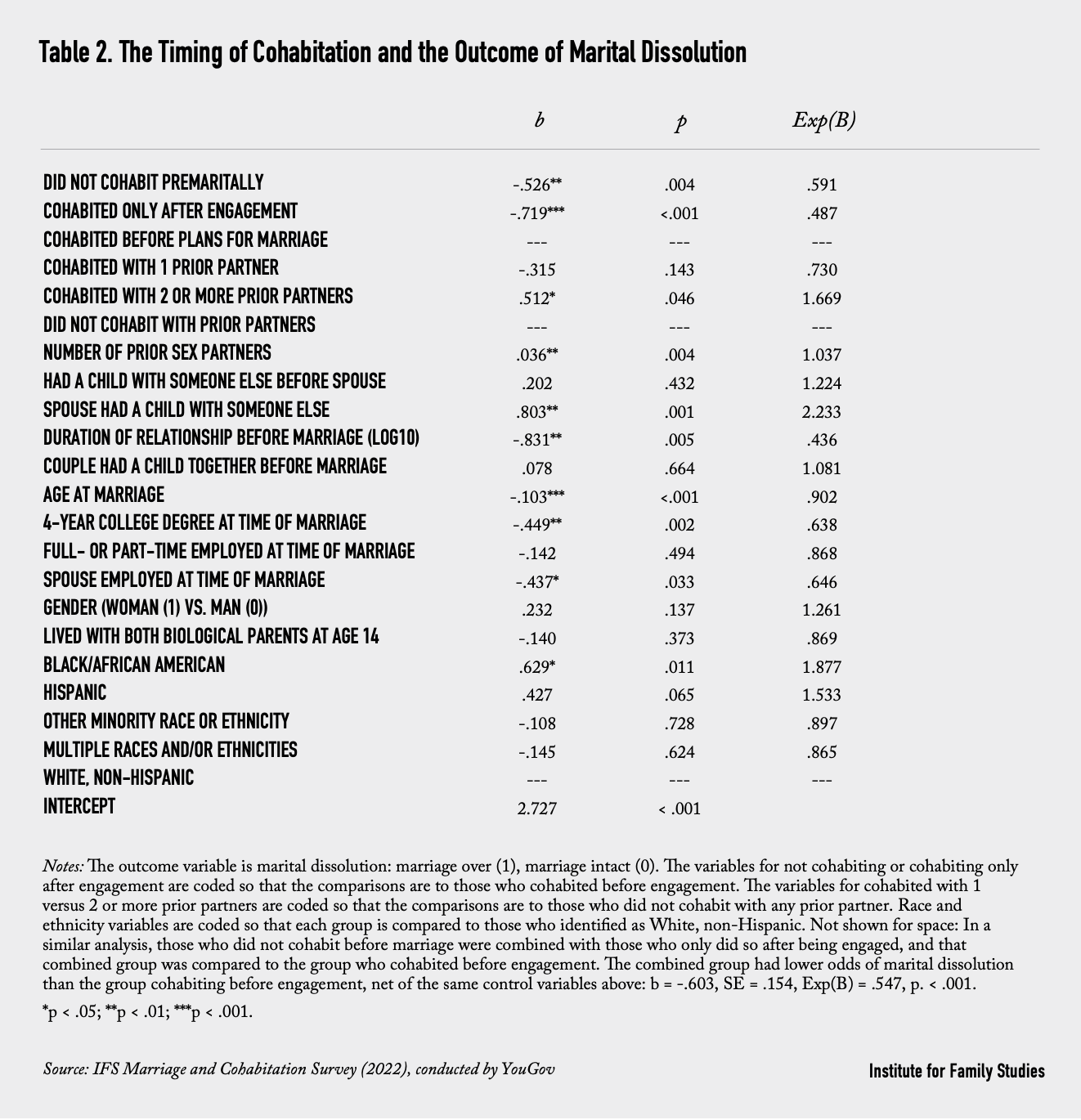

We next compared these three groups on the odds of marriages ending as of the time of our survey (for the analysis, see Table 2 in the Appendix). There was no statistically significant difference in marital dissolution between those who did not live together before marriage compared to those who only did so after being engaged. Therefore, we combine those two groups in the figure below.19

As Figure 2 depicts, those who lived together before engagement were more likely to experience marital dissolution than those who lived together only after marriage or engagement. Specifically, the marriages of those who lived together before engagement were 11 percentage points more likely to end than the marriages of the other two groups—34% compared to 23%.20

In relative terms, the marriages of those who moved in together before being engaged were 48% more likely to end than the marriages of those who only cohabited after being engaged or already married.21

Changes in Cohabitation Risks Over Time

Some scholars have speculated that risks associated with cohabitation prior to marriage would diminish or disappear altogether as cohabitation became widely accepted, because it would no longer be so rare and something mostly practiced by those already at higher risk.22 In fact, some have argued the effect has already disappeared,23 while others have argued that the effect remains and has hardly changed at all for decades.24 There is a serious argument between two groups of sociologists on this finding even though they use the same data set (but different methods).25

Regardless of that ongoing debate, we find a robust association between the timing of living together and marital dissolution, comparing those who cohabited prior to engagement, after engagement, and after (at) marriage. Thus, our primary findings focus on the timing of moving in together, and whether it occurs before or after marriage intentions have been clearly settled.26 The type of findings we present here are highly reliable, and replicate studies of premarital cohabitation from earlier decades. In fact, we have shown this same pattern regarding divorce outcomes in two prior studies, including a study of those marrying in the 1990s.27 Although the samples and other methods are different, the findings from those marrying three decades ago compared to those marrying in the last decade are quite similar.

People who move in together before having clear plans to marry—with engagement being the clearest marker of clear plans—are more likely to see their marriages end. Further, the increased risk associated with living together before being engaged exists in studies by other researchers.28 Our explanation for increased risk accepts that people have varying risks prior to such life transitions (i.e., selection), but it adds an important explanation for how the experience of cohabitation might compound or lower a person’s risks. That is, our theory of inertia and timing is not contrary to selection. We know that those who are at greater risk are also more likely to cohabit in the riskier sequence—i.e., prior to engagement.29 That does not mean that inertia and timing do not alter their risks. The important question is whether or not a person can change their trajectory. We give practical advice later based on our belief that people can change their risks and improve their odds of having a marriage that lasts.

As for the debate about whether such effects will disappear, we come down on the side that the higher risks associated with cohabitation—especially for those cohabiting before being engaged—have not disappeared. In fact, based on our theory of inertia, we do not believe these types of risks are likely to disappear because when two people move in together, they are making it harder to break up compared to not doing so. No matter the benefits they may perceive or experience, they have increased their inertia to stay together—or at least, stay together longer. We believe that timing and sequence are likely to remain important because they speak to clarity about commitment around the time of important relationship transitions.

Sidebar: Premarital Cohabitation and Marital Instability

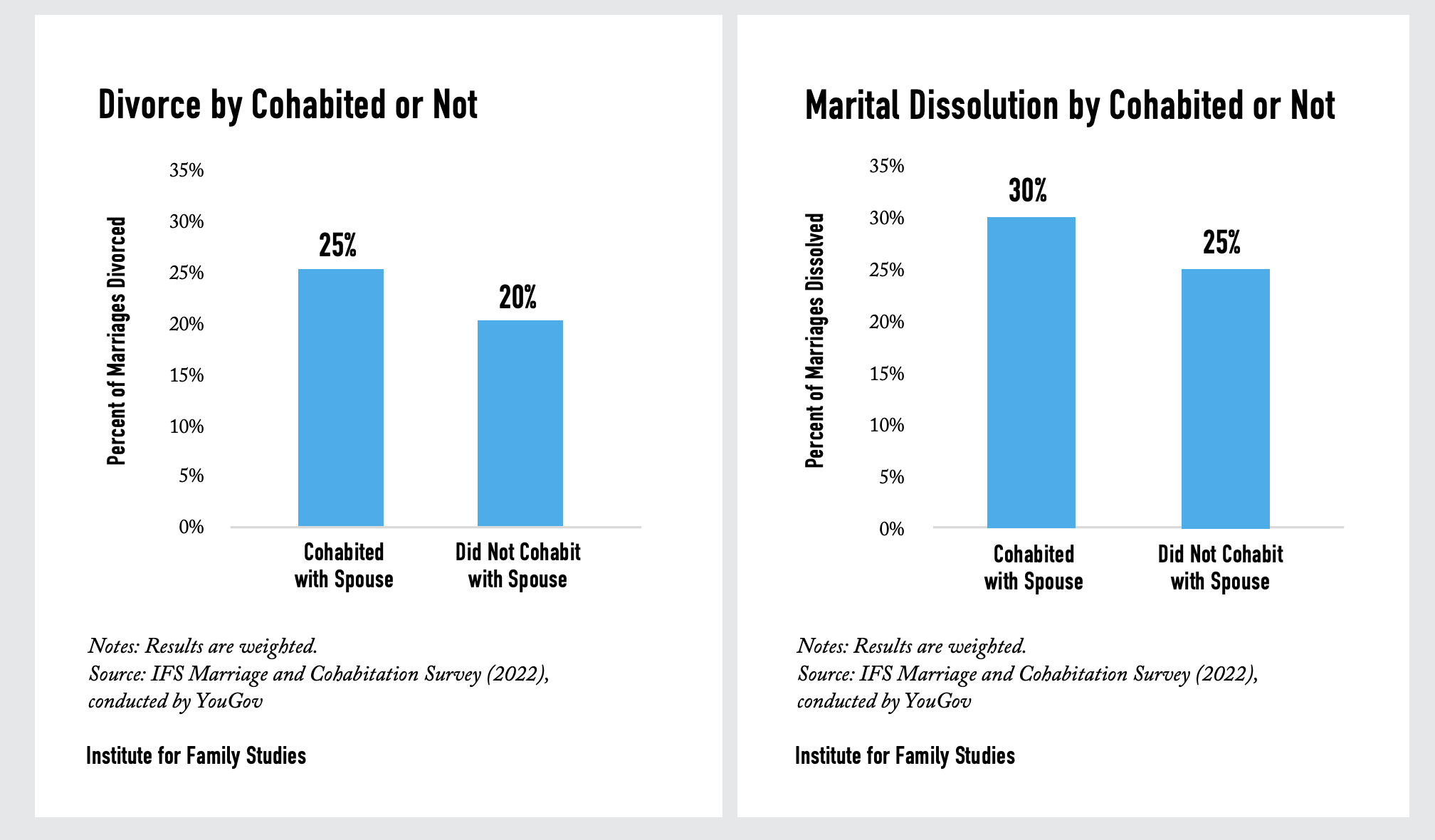

The primary finding in this report focuses on the timing of cohabitation (comparing three groups, before or after engagement, or at marriage), but there is also a strong history of research on marital instability based on the simpler, binary comparison of whether or not a couple lived together before marriage. For decades, research on marriages in the U.S. has shown that those who live with their spouse before marrying are at greater risk for seeing their marriages end.1

Although the binary comparison of living together or not before marriage is not the focus of this report, readers may want to know what this basic difference looks like in this new sample.

In the prior literature, some studies analyzed the outcome of divorce. The figure to the left shows the percentage of marriages ending in divorce in this new sample by whether or not respondents reported living with their spouse prior to marriage. Other studies have analyzed the outcome of dissolution, combining divorce and separation (as we do in the main report). The figure to the right shows the percentage of marriages ending in divorce or separation by whether or not respondents reported cohabiting with their spouse prior to marriage.

In statistical tests using this new sample, the comparisons shown above yield estimates consistent with large sample, U.S. studies that find that living together before marriage is associated with higher levels of marital instability.2

Sidebar Notes:

1. For citations, see footnote 12 in the main report.

2. Statistical tests of these differences are not the focus of this report, and tests of these differences in this sample are relatively sensitive to modeling decisions compared to those for the primary findings of this report.

Engagement versus Planning to Marry

This raises an important question, “What about those who were planning marriage but were not engaged?” In our prior work, we have sometimes combined those who reported having marriage plans with their partner and those who reported having been engaged into one group to compare to those who reported moving in together before plans or engagement.30 After all, both groups can be said to have clarified some plans for marriage before moving in together. However, in exploring these new data, those who were engaged before cohabiting were 11 percentage points less likely to end their marriages than those who reported having marriage plans but not being engaged. Further, those who reported plans to marry but were not yet engaged were only 4 percentage points less likely to end their marriages than those who reported neither being engaged or having plans to marry before moving in together.

Is there a reason to believe that being engaged is different from believing you and your partner will eventually marry?31 Although they are conceptually similar, engagement is a particularly clear signal between two people (and usually to those around them) regarding commitment and marriage intentions.32 In the context of our theory of cohabitation risk, engagement means a couple got something clearly settled beforehand about marital intentions, without room for misunderstanding.33 Because we believe that moving in together can make it prematurely harder to break up, the clarity afforded by engagement prior to cohabiting can be protective.

In contrast, having “plans” to marry is much less clear. Two partners are sometimes on different pages about commitment or commitment to marriage, and one or both may not even know it. Not surprisingly, differences in commitment are not a very good sign for a relationship.34 We will come back to this topic in our section on practical advice.

The clarity of engagement may also be important for a methodological reason. Our methods rely on retrospective reports about what was true at what point in time in the history of a relationship, not on longitudinal research where the researchers can follow people over time and carefully track how and when certain things happened. For the methods used here, engagement and its timing are likely to be less ambiguous than plans, and we believe getting engaged is reasonably likely to be recalled accurately.

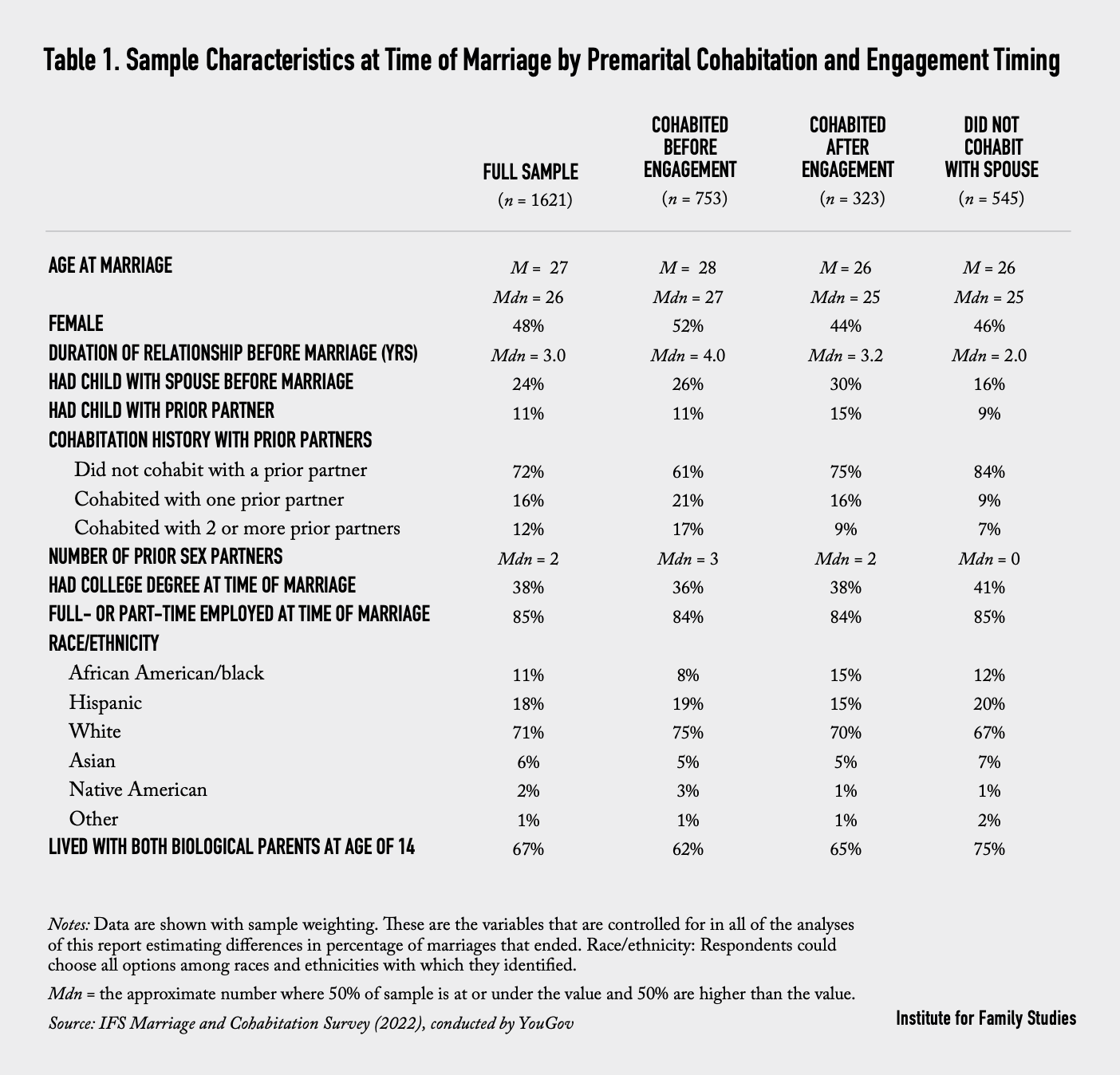

Are those who cohabited after versus before engagement simply at less risk for marital dissolution because of other characteristics (i.e., selection)? In looking at the demographic and relationship history characteristics of our sample at the time of marriage (see Table 1 in the Appendix), this does not appear to be true, at least with regard to several important characteristics. The group who cohabited after engagement appears at similar, if not greater, risk than those cohabiting before engagement on some important variables. For example, those who reported being engaged prior to moving in together were as likely, if not more so, to report having had a child with their spouse before marriage, and/or to report having a child with someone else prior to being with their spouse—both of which are clear risk factors for divorce. On the other hand, they were right in between the other two groups on whether they had ever lived with another partner. Our point is merely that this group does not seem particularly low risk for divorce based on their characteristics. These are questions for further research, as are questions about how societal changes in both marriage and engagement are related to all such variables.

II. Sliding versus Deciding into Living Together

So far, our focus has been on the timing of cohabiting prior to marriage. We also tested whether the process of how a couple came to be living together is associated with dissolution. Specifically, did the partners communicate about living together and make a decision about it together, or did they slide into living together? Prior research35 has suggested that sliding into cohabitation is the norm—most people report that it “just sort of happened.”36

We asked respondents who lived with their spouse before marriage this question:

How did you start living together?

1 = We didn’t think about it or plan it. We slid into it.

2 = We talked about it, but then it just sort of happened.

3 = We talked about it, planned it, and then made a decision together to do it.

Those answering the third option were coded as making a decision about moving in together while those answering either of the first two options were coded as sliding into living together.

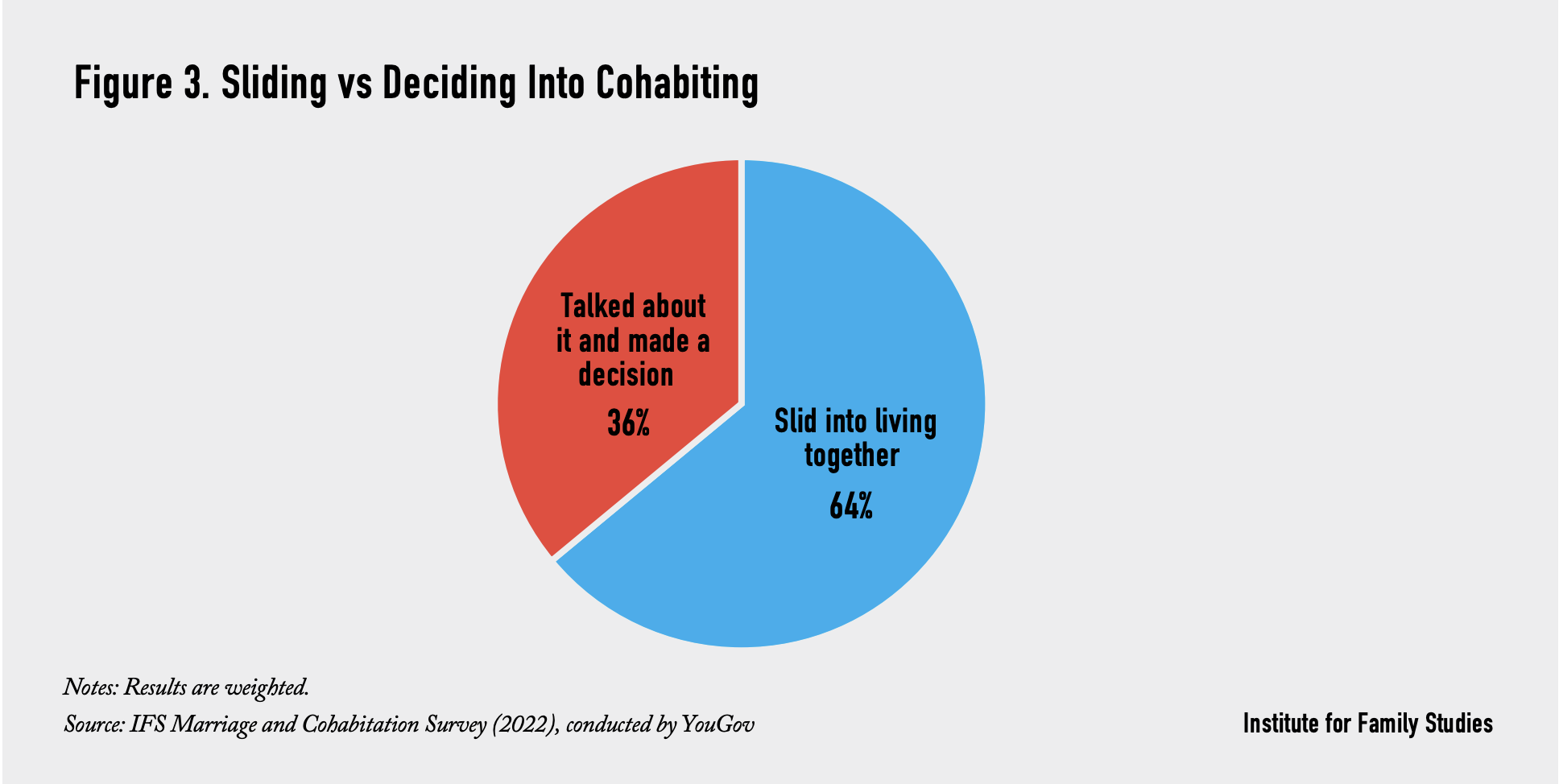

As Figure 3 shows, most people (64%) said they slid into living together and didn’t really make a decision together as a couple. That percentage is in line with other reports.37 Most partners who live together do not talk about it first and then make a decision together. Only 36% of respondents in this survey reported that they talked about it and made a clear decision.

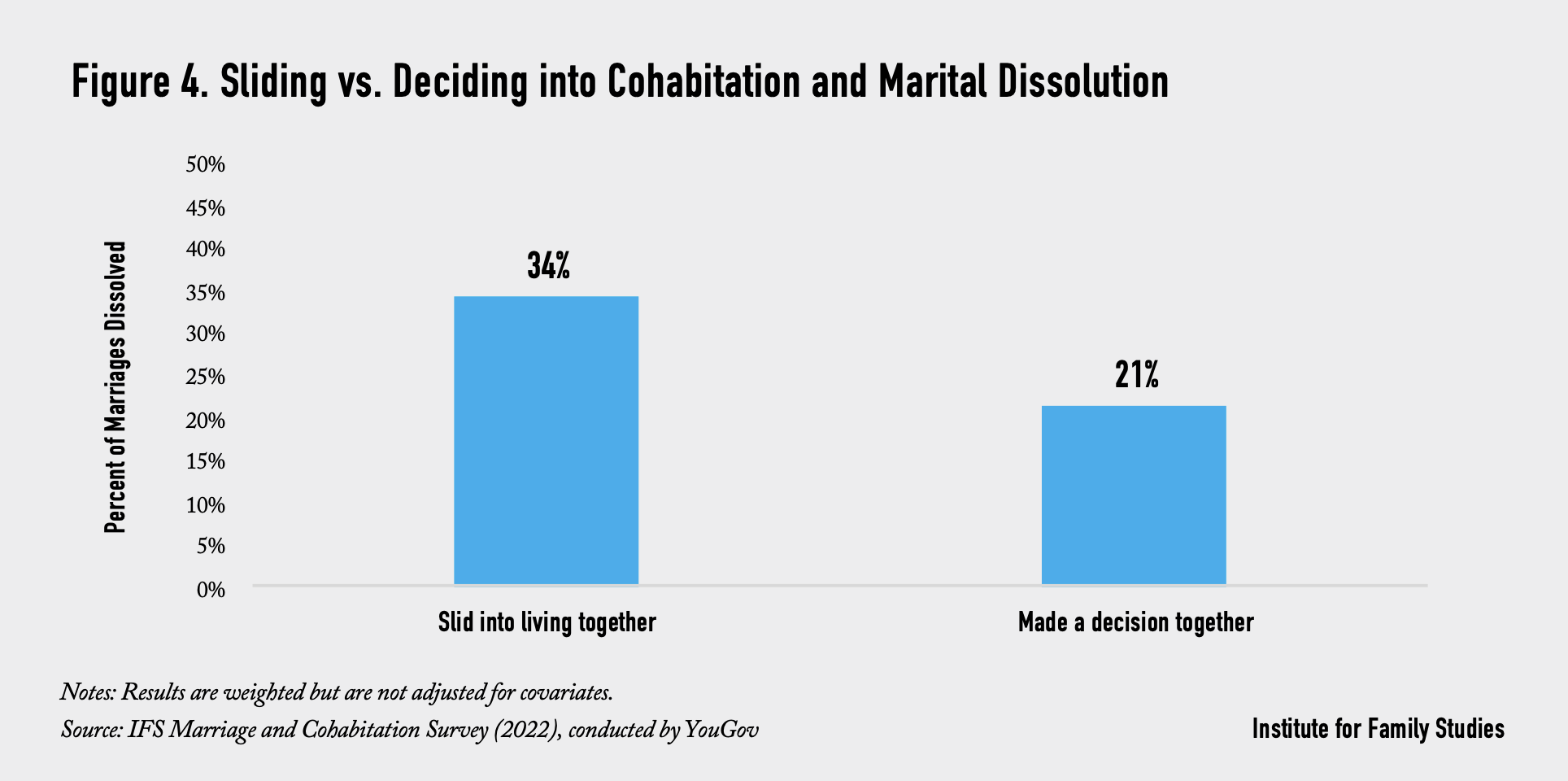

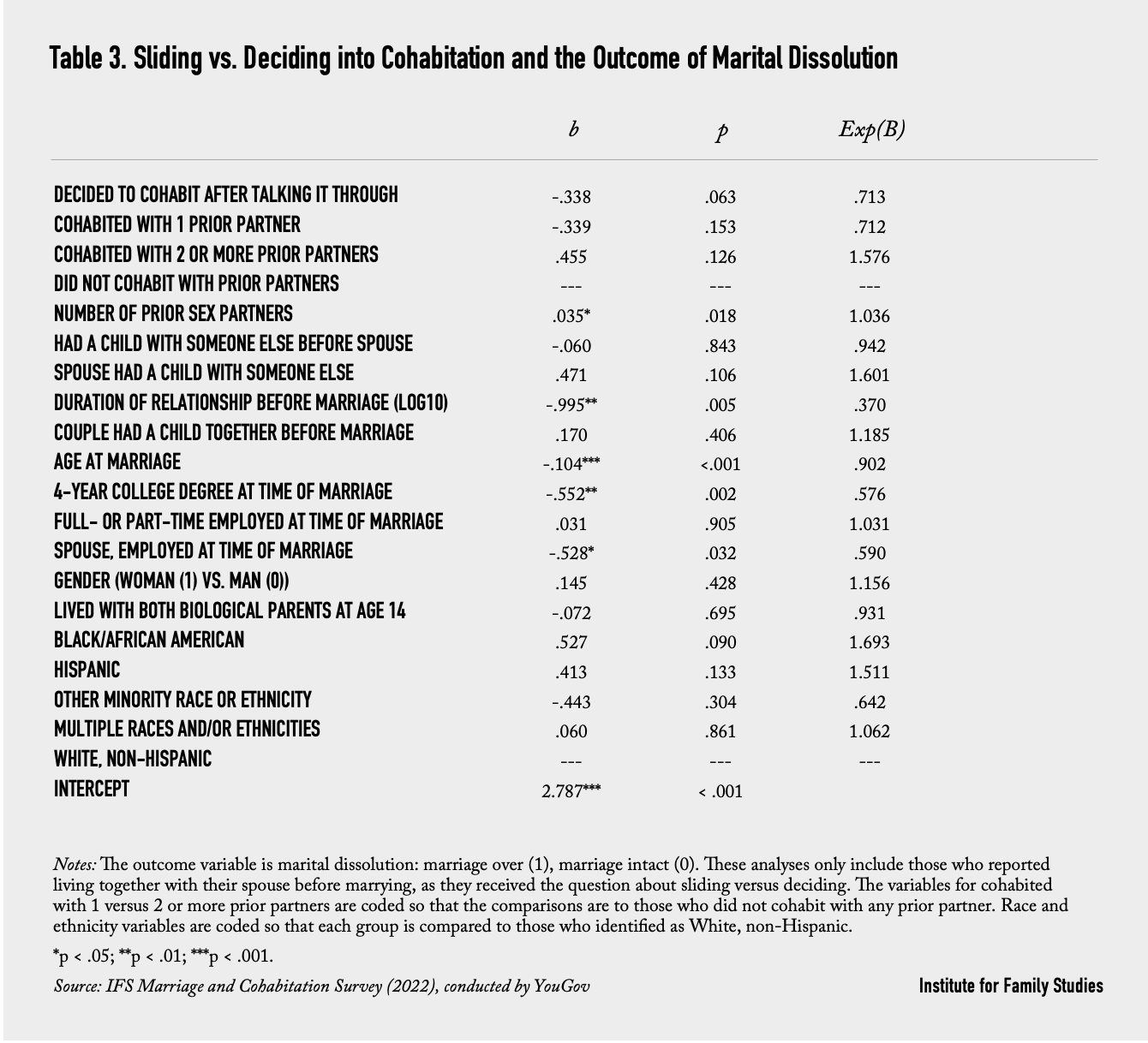

Is deciding or sliding into cohabitation associated with the likelihood of marital dissolution? Yes, with a caveat. Because the differences in outcome were so greatly affected by whether or not covariates were included in the analysis, we first present the percentages of marriages ending without adjusting for the covariates in Figure 4. As it shows, 34% of those who slid into living together saw their marriage end, compared to 21% of those who talked about it and made a decision before moving in together.

Thirteen percentage points is a large difference, and the difference is statistically significant. However, that difference reduces to only 6 percentage points when the control variables are included, and just misses the criterion for being statistically significant (for the analysis, see Table 3 in the Appendix). This suggests that most of the difference in the likelihood of dissolution based on sliding versus deciding is related to other characteristics and histories of the respondents.38 That is, among those who cohabit with their spouse prior to marriage, demographic differences and personal relationship history likely explain a good deal of the difference in whether people are able to report that they talked about the transition into living together ahead of time and made a decision with their partner about it.

That 6-point advantage for those who talked it out and made a decision might still matter.39 We noted a parallel finding in a prior report, where we were studying marital happiness, not dissolution, in a sample we had followed for years before the respondents married. Among those cohabiting prior to marriage, those who reported cohabiting after talking it over and making a decision also reported having happier marriages than those reporting sliding into living together.40 Thus, there may be some advantage for couples to slow down and talk about what they are doing, especially when making a transition that may be life altering.

III. Reasons for Moving in Together

The existing literature suggests that some specific reasons people move in together are associated with a greater likelihood of relationship difficulties or break-up than others.41 Some of the most important top reasons people give for moving in together include to test the relationship, for convenience, because of finances, or to spend more time together. In one published study of ours, among those currently cohabiting but not married (and who may or may not eventually marry), spending more time with one’s partner was associated with better quality relationships while the other reasons were associated with lower quality relationships.42

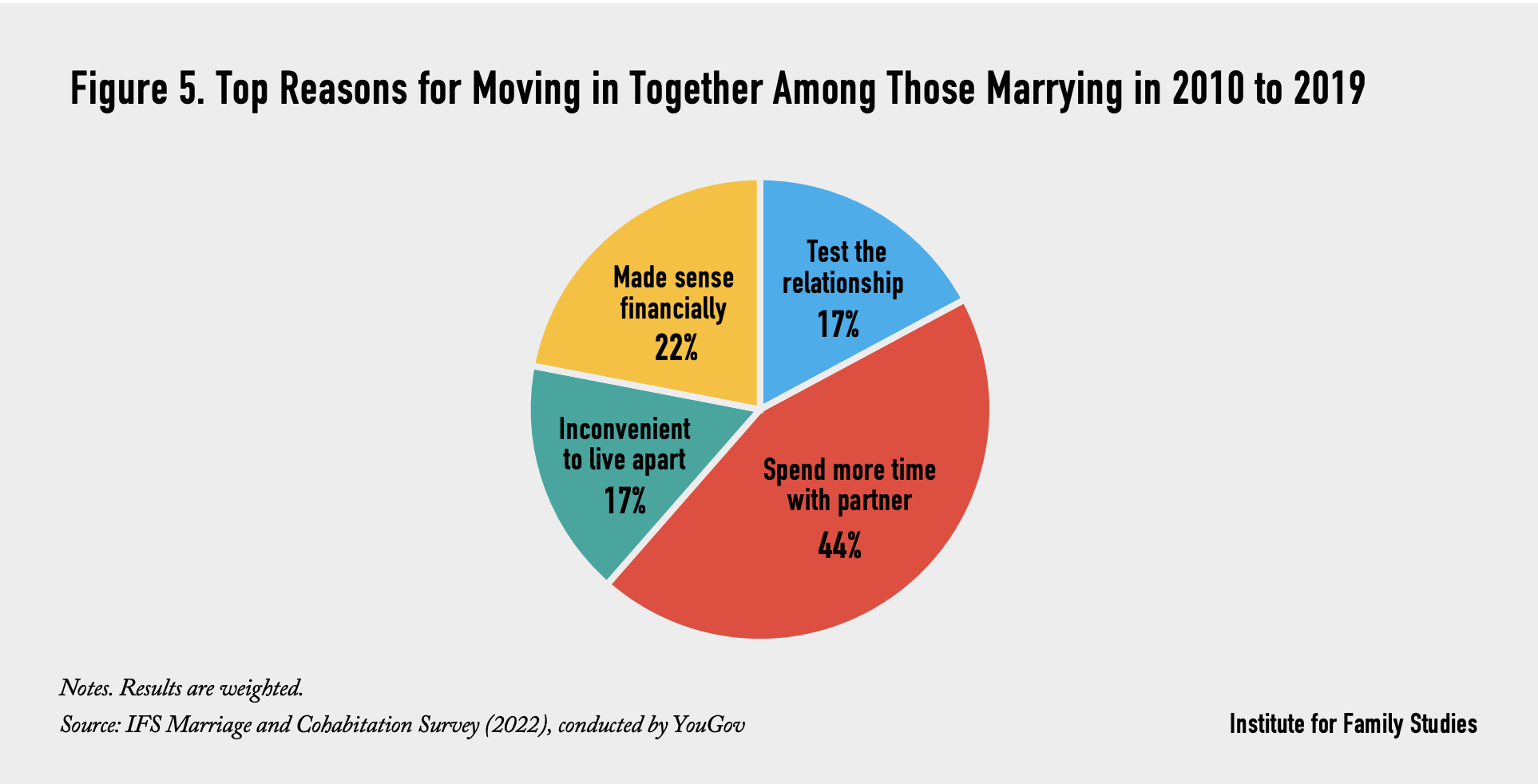

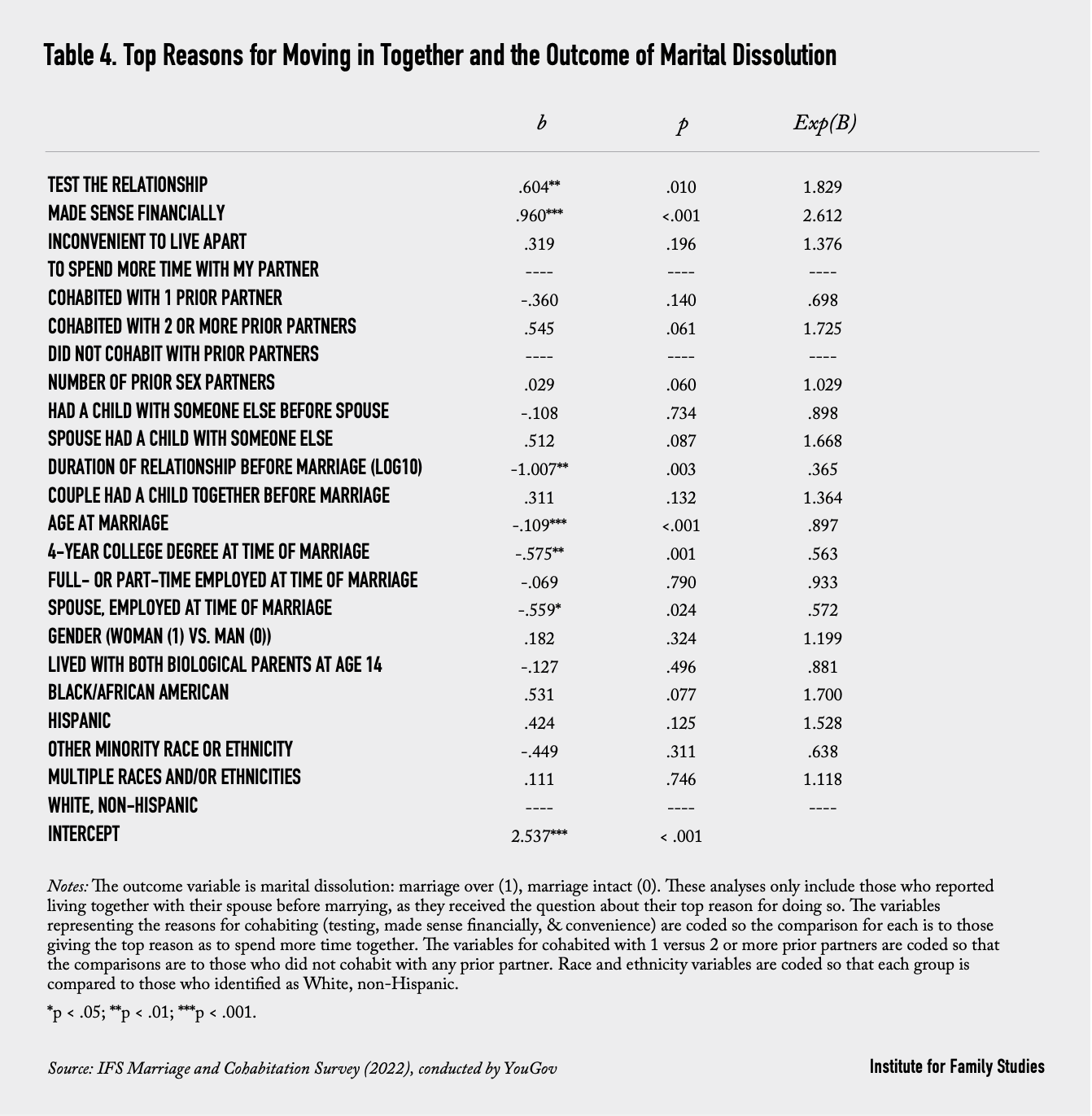

Although that prior research was not necessarily on couples who would go on to marry, we asked these same questions in the new sample to see how these reasons relate to marital dissolution among those who eventually married. Participants in the survey could choose among any of the four reasons as their top reason: to test the relationship, to spend more time with their partner, the inconvenience of living apart, or that it made sense financially.

As can be seen in Figure 5, the most frequently reported top reason to move in together was to “spend more time with my partner.”

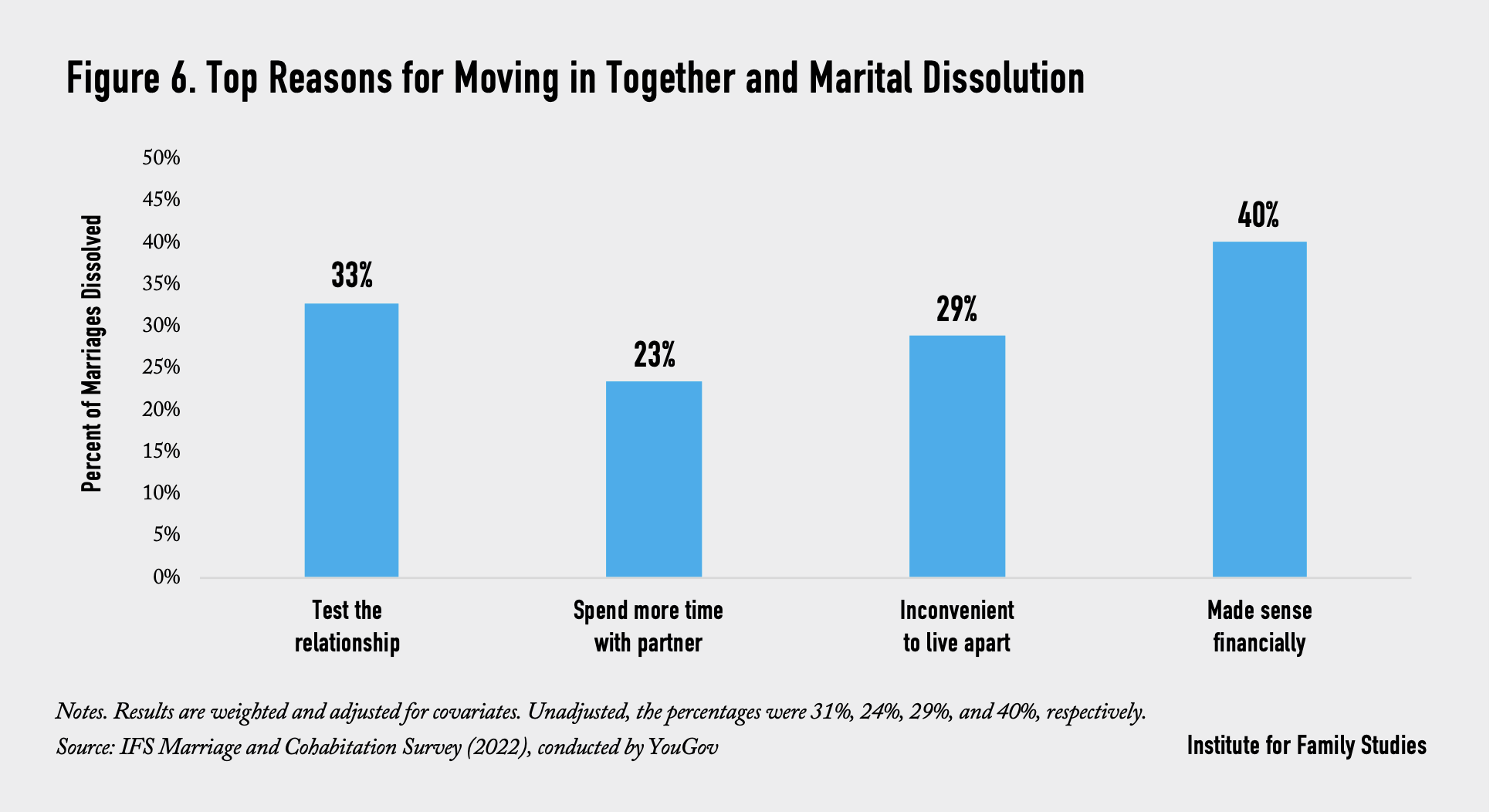

Some of the top reasons for moving in together were associated with a higher likelihood of marital dissolution than others. Figure 6 depicts the percentage of marriages that ended by the top reason given for cohabiting with their spouse.

Although it looks like the reason associated with the lowest risk for dissolution is to spend more time together, we formally tested this to see if other reasons were associated with a greater risk for dissolution than those giving that reason (for the analysis, see Table 4 in the Appendix). We found that the reasons of testing the relationship and finances were statistically associated with greater odds of dissolution than the reason of wanting to spend more time together. The results are essentially the same if we control for whether the respondents had plans to marry before moving in together.

We know that couples who have more relationship-driven reasons for important transitions like marriage or cohabitation tend to fare better than those having event-driven, external reasons.43 If a couple is going to live together before marriage, the best reason is going to be internal, perhaps having to do with commitment to one’s partner rather than because of external factors that led to the path taken, like convenience or finances. In our view, external reasons for moving in together are likely doubling down on the risk of prematurely creating inertia in a relationship, where constraints to remain together increase before a couple knows this relationship is really where they want to be, long term.

Based on our prior work on relationship quality, and the present findings, moving in together to test a relationship might be a uniquely bad reason to cohabit.44 In fact, we believe that people who are moving in together to test a relationship, as the primary reason, likely already have some concerns about the partner or the relationship. What they are doing by moving in together is making it harder to break up with someone they already have doubts about being with in the future.

IV. Prior Cohabiting Partners and the Risk for Marriages Ending

As cohabitation has become increasingly common, many people live with other partners before marrying their spouse—often called serial cohabitation. Of course, it is also true that an increasing number of people will cohabit instead of marrying. One study shows that the rise of serial cohabitation is associated with a declining intention to marry, both in terms of population changes and individual intentions.45 Many who marry will have cohabited with multiple partners beforehand, and research shows this is associated with worse odds of a marriage succeeding.46 The complexity involved has been noted by scholars who find that serial cohabitation is associated with starting to cohabit at younger ages, having lower expectations to marry, and having more premarital sexual partners.47

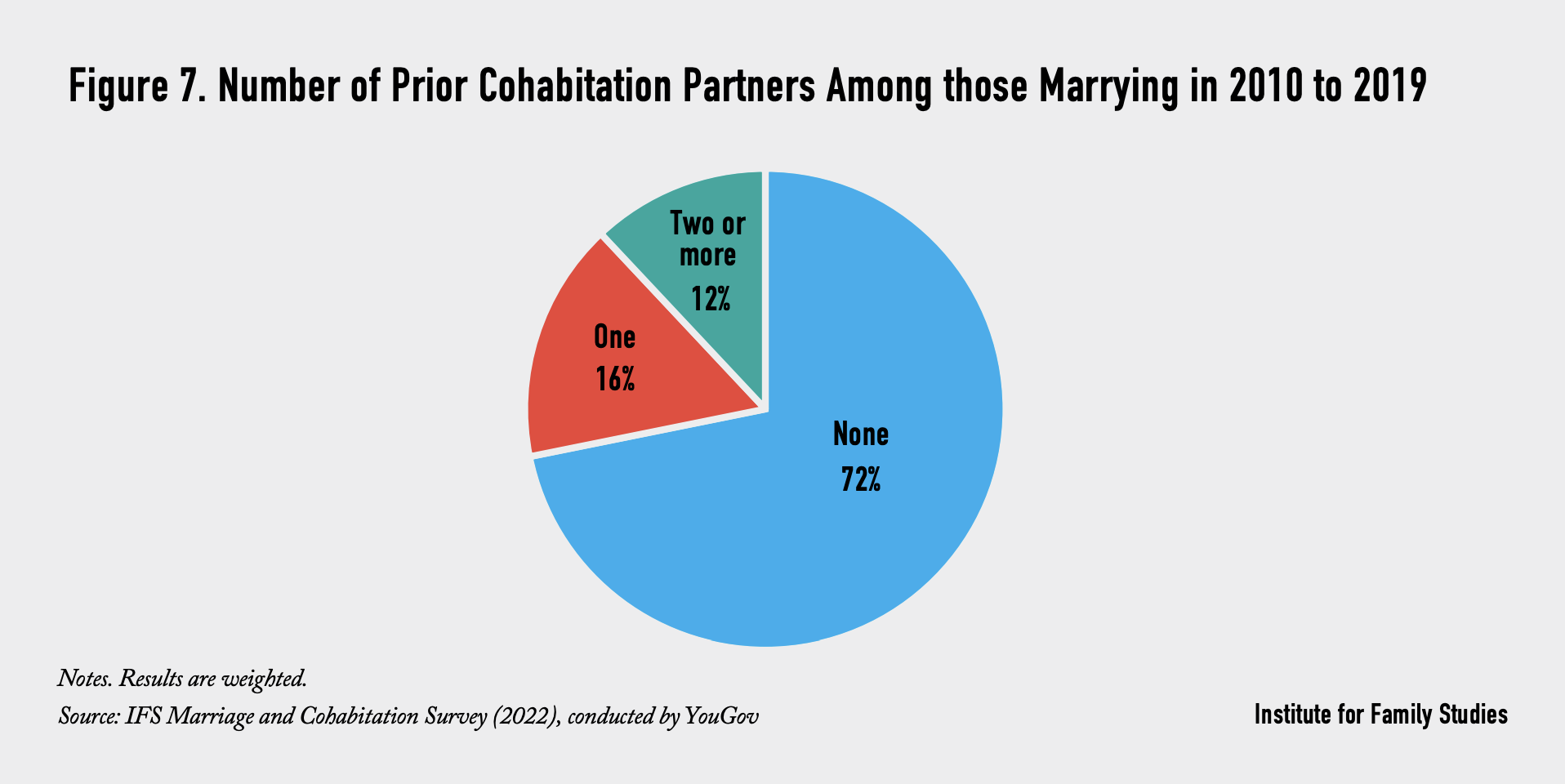

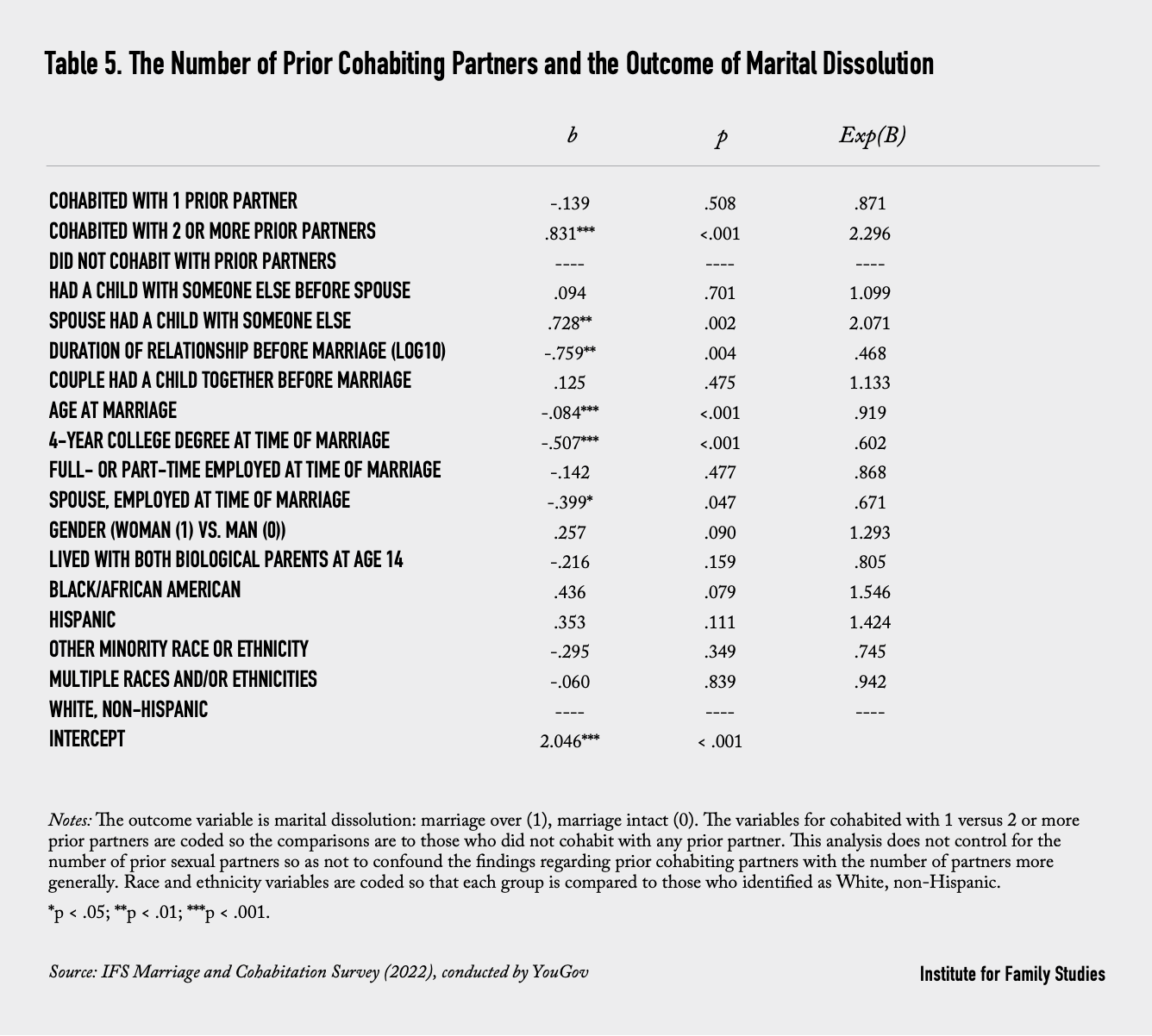

Figure 7 shows the percentage of people in our sample who lived with other partners prior to their relationship with their spouse. We summarized the prior cohabiting histories of the participants by breaking the sample down into those who never cohabited with anyone other than their spouse, those cohabiting with only one other person, and those who cohabited with two or more prior partners.

Although there are a variety of ways to estimate the percentage of people who have cohabited with more than one partner, serial cohabitation has doubled between those born in the 1950-60s compared to those born in the early 1970-80s.48 It is important to note that our sample includes only those who did marry, whereas in broader samples, those who cohabit with more than one partner are the least likely to marry.49

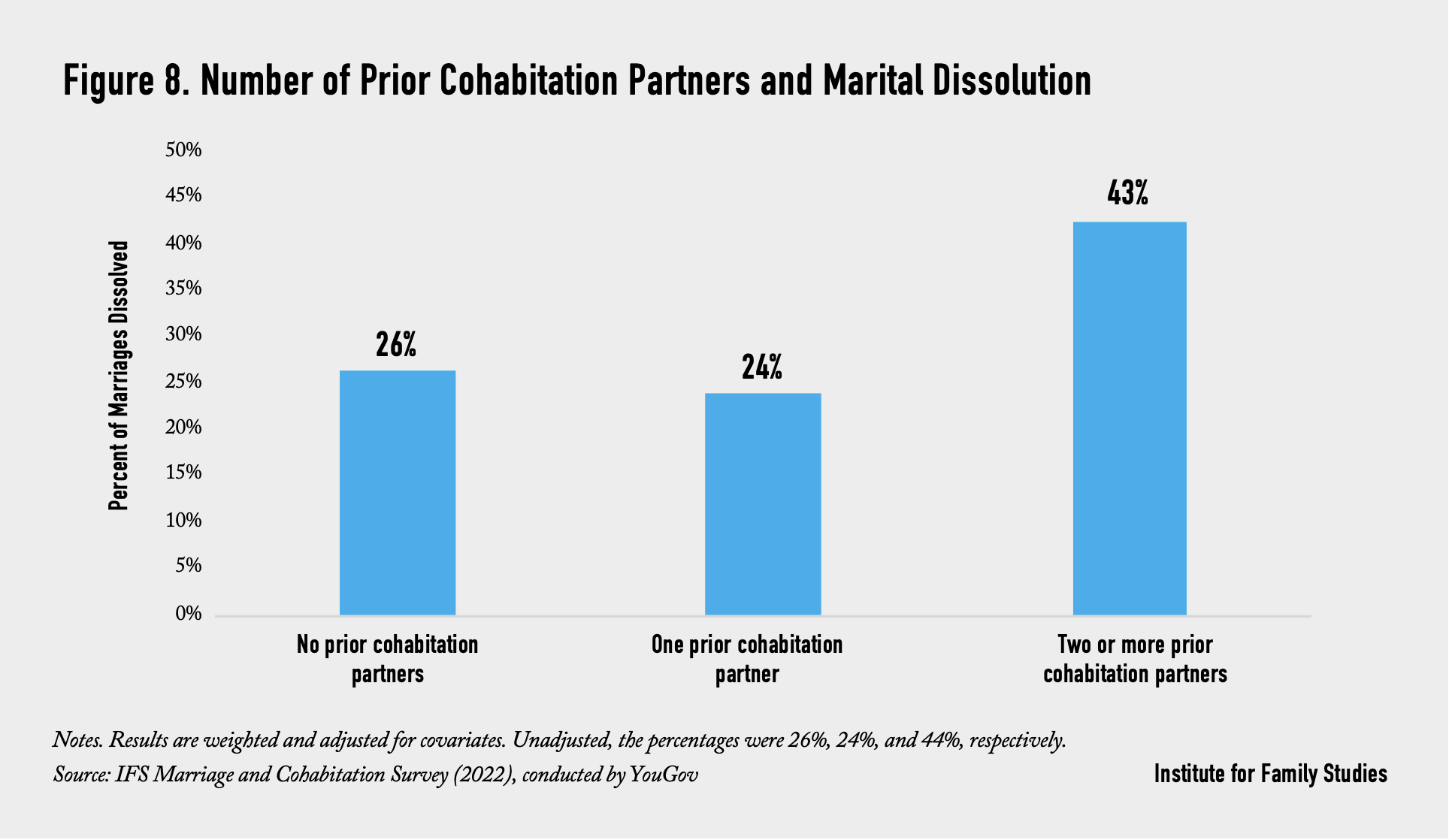

Consistent with prior research showing that cohabiting with numerous partners is associated with poor relationship outcomes, we found that having a greater number of prior cohabiting partners is associated with a higher risk of dissolution (for the analysis, see Table 5 in the Appendix).

Figure 8 displays the percentages of marriages ending by whether a person cohabited with no other partners except their spouse, with only one prior partner, or with two or more prior partners. That is, those who are in the “none” group may or may not have cohabited with their spouse, but they had not cohabited with anyone else before their spouse.

In this sample, those who cohabited with only one other person who was not their spouse, prior to marrying their spouse, were not significantly more likely to end their marriages than those who had no prior cohabiting partners.50 The group at highest risk for dissolution were those who cohabited with two or more prior partners.

Clearly, some large portion of an explanation for such findings is due to selection—differences in people that were already part of their life’s path rather than how that experience changed their outcomes. In fact, considerable research shows that having a greater number of cohabiting partners is associated with other factors such as economic disadvantage and difficult family backgrounds.51 Still, these results speak to the fact that having more experience of some types in relationships might not be beneficial.

There are likely additional challenges that affect one’s odds of marital dissolution based on cohabitation experience. A fundamental challenge to maintaining a commitment lies in how we handle alternatives to the path we are on.52 Having a greater sense that there are other options makes commitments harder to keep. Although having more relationship experience might seem like a good thing, experience may also increase one’s awareness of there being other potential, perhaps better, partners out there, which can make staying committed more of a struggle. In fact, research from decades ago showed that having more cohabiting experience could change peoples’ beliefs in favor of being more accepting of divorce.53 Updated research of that sort is needed, but there is no reason to believe that those findings no longer apply. The path a person takes in life will change their beliefs as much as beliefs will affect the pathways chosen.54

More cohabitation experience will often also mean more experience with relationships ending, which can lower barriers to divorce.55 Although no one wants to see a marriage that is dangerous or damaging continue, many couples in marriage struggle at some point, and having a sense that one can easily move on can also mean moving toward the door too quickly in a marriage that might have succeeded with more effort.

One other obvious way that having more cohabiting partners could impact the odds of divorce is related to the increased odds of having a baby with someone else before marrying. There are a couple of facts in play here. Although there are some cohabiting relationships that last many years, if not for life, cohabitating unions are far less stable than marriages,56 and the percentage of children born to cohabiting couples has grown steadily over the past several decades.57 All of these factors combine to make having more cohabiting partners associated with greater odds of having a child from a prior relationship, and multi-partner fertility is a challenge for a marriage. There is not one risk involved here, but a compounding of different types of risks that make it harder for a marriage to last.

Practical Advice for Improving the Odds for a Successful Marriage

In light of this research, many people contemplating marriage may wonder what they can do to improve their odds of staying married. Here are some suggestions based on the work we have presented here and elsewhere.

Don’t believe the hype that living together before marriage will improve your odds.

Given that most men and women believe that living together before marriage can improve their odds of success, our first piece of advice is based on a simple fact. There is virtually no evidence to support the belief that living together before marriage can improve the odds of marital stability. It may not harm the odds, especially if a person only lives with his or her future spouse after becoming engaged, but it is unwise to expect cohabiting to improve the odds that a marriage will last.

There are surely people who did move in with someone, learned something that suggested they should break up, and then did move on, and they benefitted. Yet there are likely many others who moved in with someone before knowing enough or having developed a plan, who got stuck by inertia, and eventually married someone they otherwise might have broken up with had it been easier to do.

Slow down. Timing and sequence can help you land on the right relationship path.

There are benefits to going slowly as a relationship develops. Be careful about taking steps that greatly increase the constraints for staying together until it is clear you both agree that your future is marriage. Not moving in together until marriage obviously accomplishes this goal because there is no room to misinterpret what is happening, but engagement or, for some, having clear, mutual plans to marry, can be protective. Related to the notion of believing you have plans to marry (versus actually being engaged), we expect that if two partners fully agree that marriage is the plan and publicly declare this intent to marry to their network of friends and family, then it might be pretty much like being engaged. At the same time, a lot of young men and women believe they are on the same page with their partner about marriage when they are not. Clarity matters a lot in getting the timing right.

Decide, don’t slide.

When it comes to romantic relationships, we live in the age of ambiguity.58 People avoid clarity, perhaps in the naïve belief that if they do not express their desires, then it will hurt less when they do not get what they want. If you believe this, get over it. While it is generally not a good idea to have “the talk” on a first or second date, do not avoid talking about the relationship when things are changing and becoming serious.

If you’re considering your relationship’s future, talk openly and make clear decisions, especially before any important transition. Don’t slide into circumstances that can lock you in. If you’re considering living together, you and your partner should talk about your reasons for living together, what stage in a relationship is right for living together, and your plans regarding marriage.59

In too many cohabiting relationships (and, yes, in some marriages, too), the partners have very different levels of commitment, and this is not good.60 In talking things out with a partner, you might find you are not on the same page about commitment, and that is important to know. That’s part of what is protective about only moving in together after clear plans or marriage itself. There is a lot less room for misunderstanding about the mutuality of commitment. Therefore, when we say it is important to make decisions about cohabitation, we do not merely mean a conversation like this:

“Hey, we can save some money if we just move in together. What do you think?”

“That sounds smart. Your place makes the most sense to me.”

“Great, let’s do that first of the month.”

“Okay, deal.”

That’s just logistics. We mean having a conversation or two (or more) where you talk about what you each expect and are thinking. Deciding does not guarantee success in a relationship, nor does sliding mean one is doomed. But, on balance, more marriages would last if the partners had gotten signals clear before making life-altering transitions like moving in together.

As we said earlier, don’t rush into and through important relationship transitions. Sliding is often accompanied by things happening too soon. There are increased risks for things going wrong in marriage when everything leading up to it moves too fast.61 Slow down enough to talk and make decisions about where things stand and where they are going.

Don’t move in together to test the relationship.

If you have concerns or want more information, there are many other ways to learn if the person you are dating is a good fit. Take a relationship education course, talk about what a future together would look like, and see if you are compatible by dating for a longer period of time. Take the time to see your partner in different social settings. Pay attention to how you feel with this person and how they treat others. Ask friends and family who you trust what they think. Don’t choose a way to get more information that makes it harder to act on the information that you get.

Don’t move in together to save money.

It also not a great idea to move in with someone for financial convenience. We understand how that often feels necessary, especially for those really struggling to get by. But cohabiting for external reasons, like money, is just a bad idea. As we discussed earlier, apart from other things that might matter in your life, moving in with someone because you want to be with them more is a much better reason than doing it for financial convenience. Of course, if marriage is your plan, it’s all the better that this be nailed down as a mutual goal, beforehand.

Living together already?

If you are already living with your partner, be sure that you are making decisions about your relationship that are based on your relationship, not external influences. Communicate about why you’re living together, how you got here, your expectations for the future, and what marriage would mean to each of you. Consider some of the resources listed at the end of this report to try together.

What if I am at higher risk because of living together before marriage?

We mentioned earlier that one of the ongoing arguments among researchers is about how much of the risks of cohabitation are due to selection. Remember, selection refers to the fact that people already come into a relationship with specific risk factors for struggling in marriage apart from behaviors like cohabitation history. Selection is truly part of what explains findings such as those we present here, and it includes family history, economic opportunities, education, trauma, and so forth. Further, those with more risk because of such things are also the most likely to take the riskier paths on things—like cohabitation before having very clear plans to marry. Although we control for many of these factors in this report, it is not possible to control for everything that could matter. Ultimately, you must decide if you believe that the nature of these risks could matter for you, and how.

Here’s what we believe some scholars miss. Having some characteristics that make a person more at risk for difficult relationships does not mean that those risks are unalterable. In fact, a better way to think about these risks is to use them to identify if you might especially benefit from going slower, making sure the timing of relationship transitions is right, and deciding, not sliding. One rigorous study we conducted showed that a commonly-used relationship education program (in a workshop format for couples) completely eliminated risks to marital quality and divorce for couples who had cohabited before marriage or before having clear plans to marry.62 The risks of cohabiting before there are clear plans to marry are real, but there are ways to lower the risk for those who have walked a riskier path.

If you’re concerned about your marriage, either because of your relationship history or because of current dynamics between you and your partner, work on it. Put in the effort to understand what the issues are, do your part to make it better, and don’t slide into separation. Get outside information and help. Many books, online resources, workshops, and therapy services exist to support you, including the following suggested resources.

Relationship Resources63

Online relationship education programs. There are two online programs with excellent research showing effectiveness in helping partners communicate better and strengthen their relationships. These programs could also help a couple figure out whether it makes sense for them to continue their relationship into marriage.

- OurRelationship is an online relationship education program based on a popular, effective couple therapy approach. Find it at: https://www.ourrelationship.com/

- ePREP is an online program founded in the decades of work on the Prevention and Relationship Education Program. Find it at: https://lovetakeslearning.com/

Books. There are many good books that can help a couple in their relationship or marriage. Reconcilable Differences and Fighting for Your Marriage are based on similar research-based content to the two online programs listed above. They are both general relationship support books that can help a couple improve in communication and connection, clarify expectations, and identify and solve problems. And, no, you do not have to be married to get a lot out these books.

Markman, H. J., Stanley, S. M., & Blumberg, S. L. Fighting for Your Marriage. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010)

Christensen, A., Doss, B. D., & Jacobson, N. S. Reconcilable Differences, Second Edition: Rebuild Your Relationship by Rediscovering the Partner You Love—without Losing Yourself. (New York: Guilford Press, 2014).

Premarital training or counseling. You may want to meet with someone in person for a workshop or counseling before marriage. There is evidence that these services may help prevent problems in marriages. Professional counselors or other organizations in your community may offer premarital training, and many therapists see couples before marriage, too. If you’re connected to a church or other religious institution, they may provide a premarital preparation program or have other resources.

Therapy. For couples facing problems, finding a therapist can be helpful. Many couples wait way too long before they get professional support. If you’re in relationship you’re not sure about, seeing a therapist on your own may also be helpful.

Relationship DUI video on YouTube: The team at PREP, Inc. produce a variety of resources to help people succeed in their most important relationships, including a 4-minute video that is based on our research, available on YouTube: Relationship DUI – Are you sure you’re in love?

Before “I Do” A few years ago, we authored a public report on how premarital experiences are associated with marital quality after marriage. It makes a nice companion to this report for thinking about factors associated with happy marriages based on what comes before the wedding day.

Accessible journal articles. Although this will not be of interest for many readers of this report, many of our prior research articles that have been published in peer-reviewed journals are available online (see Appendix for a list)

Appendix:

Detailed Description of Participants, Methods, and Measures

Sample

Participants. Participants in this study were individuals 50 years of age and younger who married for the first time in 2010 to 2019, who were not widowed, and whose first marriage partner was also 50 years old or younger, and who had not been married previously (N = 1,621).

Sample characteristics at time of survey. The characteristics of the analytic sample at the time of the survey response were as follows (with sample weights): The average age was 35 (Mdn = 35), 48% reported being female, and 52% reported being male. As for highest level of education completed, 3.6% reported having less than a high school education, 3.4% reported having a GED, 17.4% reported being a high school graduate, 17.9% reported having some college, 13.9% reported having an associate degree or completing a technical program, 26.0% reported having a fouryear college degree, 3.1% reported having some postgraduate education, and 14.7% reported having a postgraduate degree. Regarding employment, 64.7% reported working full time, 10.9% part time, 14.3% reported taking care of a home or family, and 5.4% reported being unemployed. The balance of categories included being a student, being retired, being disabled, or other. The median category for household, yearly income was $60,000 to $69,000, with 20% reporting less than $40,000 in household income and 20% reporting $120,000 or more in household income.

Race/ethnicity. YouGov presents respondents with a combined choice menu for how they identify regarding race and ethnicity. We requested that people be able to choose more than one category. The following percentages describe how many identified with a category, regardless of how many selections a respondent made: 10.8% reported being African American/Black, 18.2% reported being Hispanic, 71.3% reported being white, 5.8% reported being Asian, 2.1% reported being Native American, .5% reported being Middle Eastern, and 1.4% reported they did not know. For our analyses, we formed codes for if respondents identified only as being Black/African American (8.9%) or White, non-Hispanic (63.7%), or for respondents who identified as Hispanic regardless of another category selected (16.5%), and a code for those who indicated more than one category, “multiple races and/or ethnicities” (4.9%). Because of the small percentages, those who identified as Asian, Native American, Middle-Eastern, and/ or who indicated they did not know or who indicated “other” were coded into the category “other minority race or ethnicity” (6.1%). In all analyses presented here, White, non-Hispanic is the comparison group.

Family structure and relationship status. Sixty-seven percent (66.7%) of respondents reported living with both their biological parents at the age of 14. For present relationship status, 74.3% (n = 1,204) were married to their first spouse, 22.5% (n = 333) were divorced from their first spouse, and 5.2% (n = 84) were permanently separated from their first spouse (which we defined as either being separated for more than a year or indicating that they considered their marriage “over for good”). The latter two groups are those we analyzed as being in the “marital dissolution” group (see below).

Reported sample characteristics at the time of marriage. Table 1 displays characteristics at the time of marriage for the full sample as well as for the three groups based on their cohabitation history with their mate. These variables are different from those described above for the sample as of the time they were surveyed.

Procedures

Sampling and weights. YouGov is an international research data and analytics group headquartered in London. YouGov conducted this survey for the Institute of Family Studies with respondents from the United States from July 28, 2022 to August 29, 2022. A sample of 2,000 respondents who married for the first time in the years 2010 to 2019 was requested, with 1,500 respondents still married to their first spouse and 500 respondents who were divorced or separated. This choice was made to assure statistical power for assessing differences in the odds of marital dissolutionby variables of interest here (e.g., cohabitation history). The sampling decisions were optimized to test hypothesizes about cohabitation, not to provide precise estimates of the divorce rate for the prior decade.

YouGov interviewed 9,722 respondents who were then matched down to the sample of 2,000. The respondents were matched to a sampling frame on gender, age, race, and education. The frame was constructed by stratified sampling from the full 2019 American Community Survey (ACS) 1-year sample with selection within strata by weighted sampling with replacements (using the person weights on the public use file). The weights were then post-stratified on a two-way stratification of region and education (4-categories), and a four-way stratification of gender, age (4-categories), race (4-categories), and education (4-categories), a three-way stratification of age (4-categories), race (4-categories), and education (4-categories), and a two-way stratification of gender and race (4-categories) to produce the weight for the sample of 2,000. The final analytic sample was N = 1,621 as determined by the criteria described next. YouGov subsequently provided a weight for the analytic sample, which was used in all analyses and data presented in this report.

Analytic sample. The initial sample of 2,000 was reduced to the analytic sample of 1,621 by the following decisions. Thirteen respondents were excluded because they were determined to be ineligible based on variables that did not line up with screening criteria, such as being clearly married before 2010 or being over the age of 50. Another 13 respondents were excluded because they answered a key selection variable in a way where it was not possible to determine if their first marriage had ended or was intact. Although respondents were selected based on marrying in the years 2010 to 2019, that did not mean that their spouses were also in their first marriages. So that our analyses and report focused on first marriages, we excluded 283 respondents whose spouse had been married before. Similarly, we excluded 45 respondents whose first spouse was not age 50 or younger at the time of the survey as required. Twenty-nine respondents were not retained in the analytic sample because they did not identify as either male or female or they did not provide information as to their gender. Thus, our analytic sample is of those who were clearly in either a different-sex (92.5%) or same-sex marriage (6.3%). As our analyses focus on whether marriages were intact or clearly over, we excluded 8 respondents who were separated but for less than a year or who did not indicate that they thought their marriage was over. Only 1 respondent of the remaining 1,622 did not answer some of the questions used in the study analyses and was therefore excluded, resulting in a final analytic sample of N = 1,621.

Missing data. As noted above in the description of how we arrived at the analytic sample, only one person we would have otherwise included in the analyses had missing data on study variables, and we therefore elected to exclude that individual rather than impute missing data.

Measures

The timing of cohabitation and engagement. Respondents were asked a number of questions about cohabitation history. Respondents were asked “Did you and your spouse live together before marriage? That is, did you share a single address without either of you having a separate place?” with response options of “Yes” or “No.” For those who had cohabited prior to marriage, a follow-up question asked, “Had the two of you already made a specific commitment to marry when you first moved into together.” Response options were: 1) “Yes, we were engaged” 2) “Yes, we were planning marriage, but were not engaged”, or 3) “No.” As explained in the report, we focused our analyses on whether or not respondents reported being either engaged or married, versus neither, prior to moving in together. This is the same way we coded the timing and sequence of cohabitation prior to marriage in two prior studies.64

Sliding versus deciding into cohabitation. Respondents who had lived together before marriage were asked, “How did you start living together?” with possible answers being “We didn’t think about it or plan it. We slid into it,” “We talked about it, but then it just sort of happened,” or “We talked about it, planned it, and then made a decision together to do it.” Given this response scale, we dichotomized so that those answering either of the first two responses were coded as sliding into cohabitation, and those answering the third response were coded as making a decision together about it because they were literally reporting that it had been a decision if they gave that response.

Prior cohabitation history. All respondents were asked, “Before you lived with your spouse, had you ever lived with another romantic partner?” with response options being, “Yes,” or “No.” If they indicated “Yes,” they were asked, “How many other romantic partners had you ever lived with before your relationship began with your spouse?” We coded these into categories for use in analyses for number of prior cohabiting partners of 0, 1, and 2 or more.

Marital dissolution. Individuals who reported divorcing were coded as being in the marital dissolution group. Likewise, those who indicated they were separated over a year and/or who indicated that their relationship with their spouse was “over for good” were coded as being in the dissolution group.65 Thus, throughout this report, “dissolution” denotes marriages that have ended, most likely for good. This group includes those formally divorced (78.9%) and those we consider permanently separated (21.1%), many of whom will eventually formally divorce, though not all couples whose marriages end will obtain a divorce.

Covariates. Several covariates were included in analyses as control variables. Most of these variables reflect characteristics or history at the time of the marriage: age, education (college degree or not), employment status, partner’s employment status, duration of the relationship prior to marriage, number of prior cohabiting partners, number of prior sexual partners, if the couple had a child together before marriage, if the respondent had a child from a prior relationship, and if the partner had a child from a prior relationship. To address skew and/or covariates that did not meet the assumption of being linear with the logit, duration of the relationship prior to marriage was transformed with log10, and age at marriage and number of sexual partners were top coded so that the highest values were 34 and 20, respectively. The results are substantially the same, regardless of these decisions. Other covariates were not specific to the time of marriage: race, ethnicity, gender, and whether respondent lived with their biological parents together at age 14. Tables 2 – 5 show associations between all variables in each model and marital dissolution while controlling for all the other variables modeled. Table 6 displays univariate associations between the covariates and marital dissolution using single predictor logistic regressions for ease of comparison as to the association without controlling for anything else.

Analytic Strategy

All of the analyses presented in Tables 2 - 5 of this report are based on logistic regression with the outcome of marital dissolution (1, 0) regressed on the predictors shown in those tables. All analyses were conducted with the sample weights provided by YouGov. There is a literature on the complexities of using sample weights when doing multi-variate analyses, particularly when sampling weights are solely a function of variables included in models. That is not the case, here. Nevertheless, we conducted these analyses with and without the use of sample weighting, and we found no important differences in the findings. Furthermore, tests of the primary model (the timing of cohabiting related to outcome of marital dissolution) were also conducted without weights, as well as without weights but with bootstrapping, and the findings were likewise essentially the same.

All of the analyses presented in Tables 2 - 5 of this report are based on logistic regression with the outcome of marital dissolution (1, 0) regressed on the predictors shown in those tables. All analyses were conducted with the sample weights provided by YouGov. There is a literature on the complexities of using sample weights when doing multi-variate analyses, particularly when sampling weights are solely a function of variables included in models. That is not the case, here. Nevertheless, we conducted these analyses with and without the use of sample weighting, and we found no important differences in the findings. Furthermore, tests of the primary model (the timing of cohabiting related to outcome of marital dissolution) were also conducted without weights, as well as without weights but with bootstrapping, and the findings were likewise essentially the same.

Tables

Summary of Tests of Moderators or Alternate Modeling Options

We conducted a series of sensitivity tests on the primary model presented in Table 1, testing if other variables significantly moderated the associations to marriages ending for the key predictors of living together or not before marriage and, if lived together before marriage, before or after engagement. These tests explored whether or not the findings are different based on subsamples, different formation of the timing variables (i.e., engagement only or plans and engagement forming the timing groups), or outcome (i.e., including those who were separated with those who were divorced, or only including divorce as an outcome). All covariates in the primary analysis in Table 2 were included in these analyses.

Gender. Gender of respondent did not moderate these effects, meaning the effects are essentially the same regardless of gender.

Engaged vs. planning marriage. We tested if there is a difference in the findings based on whether or not those planning marriage but not engaged were placed in an “after plans for marriage” along with those who were engaged beforehand. The findings were very similar with either formation of the comparison. However, as noted in the main report, those cohabiting only after engagement had significantly lower odds of divorcing than those cohabiting only after plans to marry but not engagement, adjusting for covariates (b = -.61, p = .012, OR = 0.546), whereas those cohabiting after plans but not engagement were not significantly less likely to see their marriages end than those cohabiting before plans (b = -.19, p = .360, OR = 0.824). Hence, we combined those reporting plans to marry but who were not engaged into a group with those reporting not having plans to marry for the primary analyses.

Divorced vs. separated. We tested if the results for the primary analysis on timing of cohabiting were similar if we analyzed only those who divorced or not, versus comparing those whose marriage had ended or not (dissolution), including divorce and what we considered separations likely to be permanent, regardless of whether they had led to legal divorce. The results are essentially the same with or without those who are permanently separated included in the outcome tested. Further, the results were essentially the same if we coded permanent separation only based on being separated a year or more, without including those who were separated less than a year but who reported they believed their marriage to be over.

Recency of marriage. There has been considerable debate among scholars as to whether the cohabitation effect, as typically studied, has gone away in recent years as cohabitation has become more accepted. One group of scholars has argued that it has disappeared (Manning & Cohen, 2012) and another has argued that it has not (Rosenfeld & Roesler, 2018), with a critique (Manning, Smock, & Kuperberg, 2019) and a rejoinder (Rosenfeld & Roesler, 2020). We believe the story has likely always been the moderated story we describe here with two important groups among those who live together before marriage; indeed, the before or after commitment to marriage finding exists in the data set used by many scholars studying cohabitation (e.g., Manning & Cohen, 2012). Year of marriage (2010 to 2019) was not a significant moderator of the cohabitation timing effects. Further, the findings presented are entirely consistent with prior findings on differential outcomes in marriage that are associated with cohabitation prior to engagement or not.66

Accessible Journal Articles

Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. “The pre-engagement cohabitation effect: A replication and extension of previous findings.”Journal of Family Psychology 23 (2009): 107-111.

Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. “Couples’ reasons for cohabitation: Associations with individual well-being and relationship quality.”Journal of Family Issues 30 (2009): 233-258.

Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. “Working with cohabitation in relationship education and therapy.” Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy 8 (2009): 95-112.

Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. “The impact of the transition to cohabitation on relationship functioning: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings.”Journal of Family Psychology 26, no. 3 (2012): 348-358.

Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., Markman, H. J., & Allen, E. S. “Can marriage education mitigate the risks associated with premarital cohabitation?”Journal of Family Psychology 29, no. 3 (2015): 500-506.

Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., Amato, P. R., Markman, H. J., & Johnson, C. A. “The timing of cohabitation and engagement: Impact on first and second marriages.”Journal of Marriage and Family 72 (2010): 906-918.

Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., & Markman, H. J. “Sliding versus Deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect.”Family Relations 55, no. 4: (2006): 499-509.

Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., & Whitton, S. W. “Commitment: Functions, formation, and the securing of romantic attachment.”Journal of Family Theory and Review 2 (2010): 243-257.

Endnotes:

- Barna Group, “Majority of Americans now believe in cohabitation,” Barna, June 14, 2016.

- Graff, N. “Key findings on marriage and cohabitation in the U.S,” Pew Research Center, November 6, 2019.

- Stanley, S.M., Rhoades, G.K., & Markman, H.J. “Sliding versus Deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect.” Family Relations 55, no. 4 (2006): 499- 509.

- Hemez, P. & Manning, W. D. “Thirty years of change in women’s premarital cohabitation experience.” Family Profiles, FP-17-05. (Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research, 2017).

- Wolfinger, Nicholas, H. “Family change in the context of social changes in the U.S.” In M. Daly, N. Gilbert, B. Pfau-Effinge, & D. Besharov (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Family Policy: A life-course perspective. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023).

- Macklin, E. “Heterosexual cohabitation among unmarried college students.” The Family Coordinator 21 (1972): 463-472.

- Thornton, A., & Young-DeMarco, L. “Four decades of trends in attitudes toward family issues in the United States: The 1960s through the 1990s.” Journal of Marriage and Family 63, no. 4 (2001): 1009-1037.

- Hemez, P. & Manning, W. D. “Thirty years of change in women’s premarital cohabitation experience.” Family Profiles, FP-17-05. (Bowling Green: National Center for Family & Marriage Research, 2017).

- Vespa, J. “Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors.” Journal of Marriage and Family 76, no. 1 (2014): 207-217.

- Guzzo, K. B. “Trends in cohabitation outcomes: Compositional changes and engagement among never-married young adults.” Journal of Marriage and Family 76 (2014): 826-842.

- Lichter, D.T., Turner, R.N., Sassler, S. “National estimates of the rise in serial cohabitation.” Social Science Research 39 (2010): 754-765; Vespa, J. “Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors.” Journal of Marriage and Family 76, no. 1 (2010): 207-217.

- For a review, see: Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., & Markman, H. J. “Sliding versus Deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect.” Family Relations 55, no. 4 (2006): 499-509; as examples, see: Cohan, C. L., & Kleinbaum, S. “Toward a greater understanding of the cohabitation effect: Premarital cohabitation and marital communication.” Journal of Marriage and Family 64 (2002): 180-192; Kamp Dush, C. M., Cohan, C. L., & Amato, P. R. “The Relationship between cohabitation and marital quality and stability: Change across cohorts?” Journal of Marriage and Family 65 (2003): 539-549; DeMaris, A., & Rao, V. “Premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital stability in the United States: A reassessment.” Journal of Marriage and Family 54 (1992): 178-190; Rosenfeld, M. J., & Roesler, K. “Cohabitation experience and cohabitation’s association with marital dissolution.” Journal of Marriage and Family 81, no.1 (2018): 42–58.

- This history of this argument is well explained in Smock, P.J. “Cohabitation in the United States: An appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (2000): 1-20; For a classic on this subject, see: Lillard, L. A., Brien, M. J., & Waite, L. J. “Premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital dissolution: A matter of self-selection?” Demography, 32 (1995): 437-457; James, S. L., & Beattie, B. A. “Reassessing the link between women’s premarital cohabitation and marital quality.” Social Forces 91 no. 2 (2012): 435-662.

- Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. “The pre-engagement cohabitation effect: A replication and extension of previous findings.” Journal of Family Psychology, 23 (2009): 107-111; Rosenfeld, M. J., & Roesler, K. “Cohabitation experience and cohabitation’s association with marital dissolution.” Journal of Marriage and Family, 81 no. 1 (2018): 42–58.

- Axinn, W. G., and Barber, J. S. “Living arrangements and family formation attitudes in early adulthood.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 59 (1997): 595-611.

- Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. “The impact of the transition to cohabitation on relationship functioning: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings.” Journal of Family Psychology, 26 no. 3 (2012): 348-358.

- Kline, G. H., Stanley, S. M., Markman, H. J., Olmos-Gallo, P. A., St. Peters, M., Whitton, S. W., & Prado, L. “Timing is everything: Pre-engagement cohabitation and increased risk for poor marital outcomes.” Journal of Family Psychology

- (2004): 311-318; This theory is covered extensively in Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., & Markman, H. J. “Sliding versus Deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect.” Family Relations 55 no. 4 (2006): 499-509. 18 Glenn, N. D. “A plea for greater concern about the quality of marital matching.” In A. J. Hawkins, L. D. Wardle, and D. O. Coolidge (Eds.), Revitalizing the Institution of Marriage for the Twenty-first Century: An agenda for strengthening marriage (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2002): pp. 45-58

- Unadjusted, marital dissolution occurred for 33% of those living together before engagement, 23% of those living together after engagement, and 25% of those not living together until marriage (adjusted, 34%, 21%, & 24%).

- As noted in the “About the Data and Methods” box, as well as the methods section of the Appendix, our primary analyses are logistic regression, but we translate differences in odds into estimated likelihoods (e.g., the percentage of those divorced by groups) because probabilities are more understandable than odds for most readers. These are the estimated percentages of those divorced for this sample, net of the covariates.

- How did we get that number? The weighted average percentage of marriages ending among those in the combined group of those not cohabiting until after engagement or not cohabiting before marriage is 23%, which is 11 percentage points lower than the group cohabiting before engagement. Thus, 11/23 = .48, or a 48% greater likelihood of dissolution.

- Kamp Dush, Cohan, and Amato speculated about this but found the data were not consistent with the thesis in terms of diminishing risks over time: Kamp Dush, C. M., Cohan, C. L., & Amato, P. R. “The Relationship between cohabitation and marital quality and stability: Change across cohorts?” Journal of Marriage and Family 65 (2003): 539-549.

- Manning, W. D., & Cohen, J. A. “Premarital cohabitation and marital dissolution: An examination of recent marriages.” Journal of Marriage and Family 74 (2012): 377- 387.

- Rosenfeld, M. J., & Roesler, K. “Cohabitation experience and cohabitation’s association with marital dissolution.” Journal of Marriage and Family 81, no. 1 (2019): 42–58.

- Manning, W. D., Smock, P. J., & Kuperberg, A. “Cohabitation and marital dissolution: A comment on Rosenfeld and Roesler (2019).” Journal of Marriage and Family 83, no. 1 (2021): 260-267; Rosenfeld, M. J., & Roesler, K. “Premarital cohabitation and marital dissolution: A reply to Manning, Smock, and Kuperberg.” Journal of Marriage and Family 83, no. 1 (2021), 268-279.

- Brown and Booth published a finding that seems similar but is quite different. They found that cohabiters with marriage plans were closer in relationship quality to those who were married, while those who did not have marriage plans had lower quality relationships. Our focus on marriage plans (specifically engagement) is not solely about if a cohabiting couple has them but about when they formed them, as that is the key question related to the risk of inertia. Further, our focus here is on eventual outcomes in marriage, not present relationship quality. Brown, S. L., & Booth, A. “Cohabitation versus marriage: A comparison of relationship quality.” Journal of Marriage and Family 58 (1996): 668-678.

- Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., Amato, P. R., Markman, H. J., & Johnson, C. A. “The timing of cohabitation and engagement: Impact on first and second marriages.” Journal of Marriage and Family 72 (2010): 906-918. We have also published numerous studies showing that the difference in timing of cohabitation is associated with the relationship quality.

- Goodwin, P. Y., Mosher, W. D., & Chandra, A. “Marriage and cohabitation in the United States: A statistical portrait based on Cycle 6 (2002) of the National Survey of Family Growth.” Vital Health Stat 23 (28). (Washington D.C.: National Center for Health Statistics, 2010); Manning, W. D., & Cohen, J. A. “Premarital cohabitation and marital dissolution: An examination of recent marriages.” Journal of Marriage and Family 74 (2012): 377-387.

- Kline, G. H., Stanley, S. M., Markman, H. J., Olmos-Gallo, P. A., St. Peters, M., Whitton, S. W., & Prado, L. “Timing is everything: Pre-engagement cohabitation and increased risk for poor marital outcomes.” Journal of Family Psychology 18 (2004): 311-318.

- Rhoades, G. K., & Stanley, S. M. Before “I Do”: What do premarital experiences have to do with marital quality among today’s young adults? (Charlottesville, VA: National Marriage Project, 2014).

- In many studies, including some of our own, those who report being engaged or having plans are combined into one group, which makes sense for certain research questions. Both Vespa (2014) and Guzzo (2014) combine these responses in their analyses of how many people report having plans to marry prior to cohabiting, and whether or not relationships continue at all, and/or continue on into marriage, after cohabiting: Vespa, J. “Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors.” Journal of Marriage and Family 76, no. 1 (2014): 207-217; Guzzo, K. B. “Trends in cohabitation outcomes: Compositional changes and engagement among never-married young adults.” Journal of Marriage and Family 76 (2014): 826-842.

- This and its consequences are discussed in Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., & Whitton, S. W. “Commitment: Functions, formation, and the securing of romantic attachment.” Journal of Family Theory and Review 2 (2010): 243-257.

- Unfortunately, our data do not include a question about whether a person ever reports having been engaged prior to marrying, only if prior to cohabitation. 34 Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., Scott, S. B., Kelmer, G., Markman, H. J., & Fincham, F. D. “Asymmetrically committed relationships.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships

- (2017): 1241–1259; Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., Markman, H. J. “Pre-engagement cohabitation and gender asymmetry in marital commitment.” Journal of Family Psychology, 20 (2006): 553-560.

- Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. “Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data.” Journal of Marriage and Family 67, no. 4 (2005): 989 - 1002; Lindsay, J. M. An ambiguous commitment: Moving into a cohabiting relationship. Journal of Family Studies 6, no. 1 (2000): 120-134.

- Isabel Sawhill has made a similar point about how people come to have children, emphasizing drifting versus planning: Sawhill, I. V. Generation Unbound: Drifting into sex and parenthood without marriage. (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2014).

- Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., & Fincham, F. D. “Understanding romantic relationships among emerging adults: The significant roles of cohabitation and ambiguity.” In F. D. Fincham & M. Cui (Eds.), Romantic Relationships in Emerging Adulthood (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011): 234-251.

- There is no other analysis here where the findings are so appreciably different with or without covariates, and we highlight this point to note what it likely means.

- As can be seen in Table 3 (see Appendix), the analysis with the covariates has a p-value of .06 rather than being well under .05 like other findings we note. Given that the result is expected and theoretically consistent with prior work, we believe that the finding is interpretable as a real difference.

- Rhoades, G. K., & Stanley, S. M. Before “I Do”: What do premarital experiences have to do with marital quality among today’s young adults? (Charlottesville, VA: National Marriage Project, 2014).

- Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. “Couples’ reasons for cohabitation: Associations with individual well-being and relationship quality.” Journal of Family Issues 30 (2009): 233-258; See also: Bumpass, L. L., Sweet, J. A., & Cherlin, A. “The role of cohabitation in declining rates of marriage.” Journal of Marriage and Family 53 (1991): 913-927; Sassler, S. “The process of entering into cohabiting unions.” Journal of Marriage and Family 66 (2004): 491-505.

- Ibid. Rhoades et al., 2009.

- Surra, C. A., & Hughes, D. K. “Commitment processes in accounts of the development of premarital relationships. Journal of Marriage & the Family 59, no. 1 (1997): 5-21.

- Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. “Couples’ reasons for cohabitation: Associations with individual well-being and relationship quality.” Journal of Family Issues 30 (2009): 233 - 258.

- Vespa, J. “Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors.” Journal of Marriage and Family 76, no. 1 (2014): 207-217.

- Lichter, D.T., Turner, R.N., Sassler, S. “National estimates of the rise in serial cohabitation.” Social Science Research 39 (2010): 754-765.

- Cohen, J., & Manning, W. “The relationship context of premarital serial cohabitation.” Social Science Research 39 (2010): 766-776.

- Eickmeyer, K. J., & Manning, W. D. “Serial cohabitation in young adulthood: Baby Boomers to Millennials.” Journal of Marriage and Family 80, no. 4 (2018): 826- 840; Vespa, J. “Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors.” Journal of Marriage and Family 76, no. 1 (2014): 207-217.

- Vespa, J. “Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors.” Journal of Marriage and Family 76, no. 1 (2014): 207-217.

- Teachman found decades ago that premarital cohabitation limited only to one’s mate was not associated with greater odds of divorce. This finding is a bit different and bears testing in future research. Teachman, J. D. “Premarital sex, premarital cohabitation, and the risk of subsequent marital dissolution among women.” Journal of Marriage and Family 65, no. 2 (2003): 444-455.

- Lichter, D.T., Turner, R.N., Sassler, S. “National estimates of the rise in serial cohabitation.” Social Science Research 39 (2010): 754-765; Sassler, S., & Miller, A. “Cohabitation nation: Gender, class, and the remaking of relationships.” (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017).