Highlights

This month is Women’s History Month—and it’s great to see coverage spotlighting the achievements of women in history and up to the present day. But in a month focused on women, the character and function of femininity in women’s lives has gone largely unexamined.

That’s probably because our current culture’s fixation on gender flexibility and equality makes such exploration difficult. Elite culture most often celebrates women who embrace more masculine models of life, from the C-suite (think Sheryl Sandberg) to pop culture (think “Captain Marvel.”) In fact, the message from the culture’s commanding heights seems to be that there is no value for girls and women in embracing a distinctive and traditional feminine identity in the 21st century.

But that message doesn’t seem to be getting across to ordinary women across America, the majority of whom see themselves as “very feminine.” That’s according to data collected recently in the U.S. Adult Sexual Behaviors and Attitudes survey, conducted by one of us. The nationally representative study of adults ranging in age from 18 to 74 has a margin of error of plus or minus 3%.

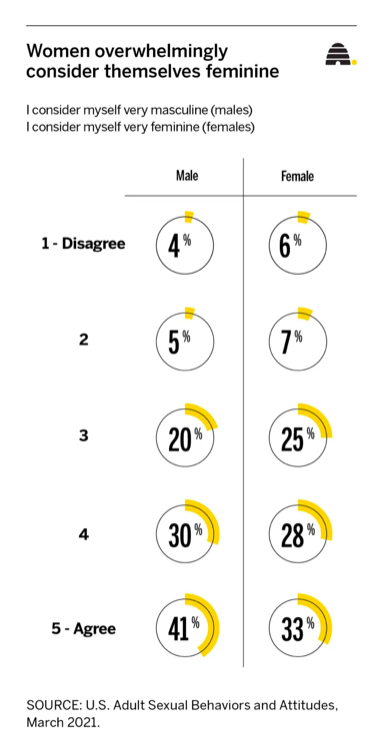

While the survey did not define femininity, a clear majority of 814 women surveyed in March 2021 identified as “very feminine” on a 5-point scale, with 61% selecting 4 or 5 on the scale. This lags only slightly behind men who are more likely to score themselves as very or somewhat masculine. Both men and women are equally likely to be content with their level of masculinity or femininity—80% of men and 77% of women agree that they are “happy with how masculine or feminine they are.”

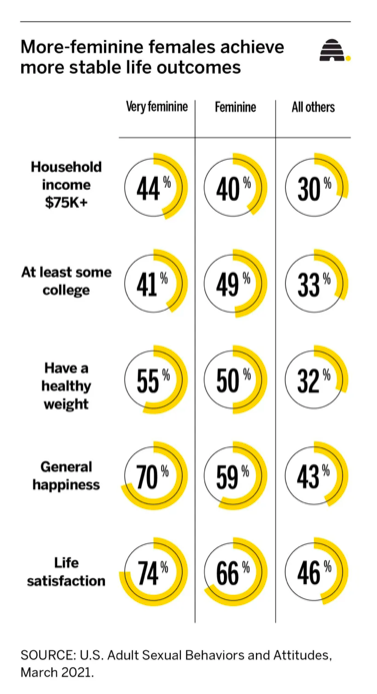

Lest we be disappointed that these self-described feminine women are missing their chance to lean into a more gender-fluid life, an analysis of the data suggests that the degree of femininity correlates with seemingly positive outcomes of women’s lives.

Financial situation, personal health, general happiness, and life satisfaction were all markedly better among those who express the highest levels of femininity. The only exception is in their experience of college.

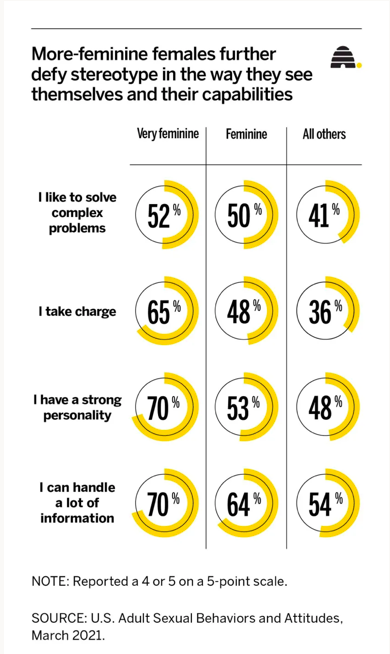

But the findings weren’t just about women and their well-being alone. In the study, the women who described themselves as “feminine” were the most likely to marry and to say they have fulfilling marriages across various dimensions, including strong personal relationships and community involvement. High-femininity females were also, according to the study, more likely to describe themselves as able to take risks, manage uncertainty and self-regulate, which may help to explain lower rates of depression compared to other women.

Moreover, the self-described “very feminine” women in the study agreed at a much higher rate than other women that they “have a strong personality” and like to solve problems and take charge.

While these findings might be controversial in a time in which gender identification and gender roles are hotly debated, they may also be liberating for women who tend to find meaning or joy in feminine expression. In some ways, the “traditionally feminine”—characterized by concern, responsibility and care for others—has undergone devaluation for decades.

That was an understandable response to problematic limitations on women’s spheres of influence. Regrettably, though, as scholar Jean Elshtain explains, women were simultaneously required to “embrace the terms of a public life that was created by men who had rejected or devalued the world of the traditionally ‘feminine,’” rather than developing a truer cultural understanding of femininity.

But the findings from this survey raise questions about whether women have rejected this eradication of the feminine and have instead embraced it. For many of these women, rather than being a problem, femininity in the 21st century is a powerful resource.

While the women in the survey undoubtedly define femininity in different ways, the data should encourage women who take issue with being told that to succeed, they have to be more like men. Nearly 60 years after Betty Friedan set off the second wave of feminism with her book “The Feminine Mystique,” the data shows that it’s not just OK to be feminine, but that it’s a healthy and powerful reality for many women.

It was awareness of the power of their distinctive femininity that brought working and middle-class women together to be the dominant force in changing a culture of conflict in Northern Ireland after 25 years of violent struggle. In Nigeria, women united by their shared feminine wisdom set aside decades of prejudice to join in peaceful protest, ultimately barricading the assembly room where leaders held peace talks, refusing to leave until warring parties signed a cease-fire ending 14 years of bloody civil war.

More recently, news is filled with the stories of brave Ukrainian women confronting Russian soldiers, some with no more than the moral force of their indignation at the unjustified attack against their homes and families. As U.S. Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield recently wrote, the same Ukrainian women who have been critical to “building a burgeoning democratic society,” now stand with their distinct feminine courage to protect and care for their children, families and communities in spite of imminent violence all around them.

The truth about femininity as it is experienced by many women today is that it is a powerful resource that animates and fulfills many more modern women than is often understood or appreciated. If society is serious about supporting women, it must do a better job of supporting the whole range of what femininity offers.

Jenet Jacob Erickson is an affiliated scholar of the Wheatley Institution at Brigham Young University. James McQuivey, who holds a doctorate, is a consumer behaviorist analyst and has taught at Boston University and Syracuse University. Brad Wilcox is a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared at The Deseret News and has been reprinted here with permission.