Highlights

- Those who express trust in others are much more likely to enjoy positive outcomes and engage in a host of pro-social activities. Post This

- The share of Americans who spend a social evening with a neighbor at least several times per month has declined from 44% in 1974 to 28% in 2022. Post This

- Over the past 50 yrs, we've become about half as likely to spend any social time w/ our neighbors; we’ve also become half as likely to trust our fellow Americans. Post This

This past April, a group of young women were searching for their friend’s house in a rural upstate New York town, and accidently pulled into the wrong driveway after losing cell service. Shortly after realizing their mistake and beginning to back out, the women were met with gunfire from the homeowner, killing a 20-year old passenger. One week earlier, in Kansas City, a 16-year-old boy approached a house in his own neighborhood to pick up his younger siblings, and after ringing the doorbell of the wrong house, he was shot through the door. And just weeks ago, a college junior was fatally shot by his neighbor in Columbia, South Carolina, after mistaking another house for his own.

When social scientists speak of declining social trust and deteriorating communities, it can be difficult to put a face to the name. Nuances of each case notwithstanding, these three incidents should be understood as casualties of declining trust and neighborliness—both of which have been in sharp decline over the past half-century.

For decades, surveys have asked a representative sample of Americans a simple question to measure their trust in others: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can't be too careful in dealing with people?” The resulting measure, displayed in Figure 1 below, captures what social scientists call “generalized social trust” or an individual’s trust in a “generalized other.” Despite the simplicity of this measure, those who express trust in others are much more likely to enjoy positive outcomes and engage in a host of pro-social activities.

Asking people whether they generally trust others differs in key ways from asking whether people trust particular individuals in their lives. People tend to have much higher levels of trust in their close personal contacts—such as friends and family—compared to a generalized other. High levels of trust in close social connections tends to produce what preeminent political scientist Robert Putnam referred to as “bonding social capital.” But generalized social trust measures people’s trust in their fellow members of society. This type of trust helps develop “bridging social capital,” allowing us to more easily forge connections across divides.

In generations past, one’s neighbors would more likely be considered members of bonding networks rather than our bridging networks—members of the in-group rather than the out-group. Even if our parents or grandparents weren’t best friends with their neighbors, they certainly wouldn’t relegate them to the obscure and foreign category of “generalized others.”

But this isn’t the case today. According to a 2018 survey from the Pew Research Center, only a quarter of Americans said that they know most of their neighbors. A similar share of Americans are unable to provide any specific information about their neighbors—even as little as their names. Given the further erosion of community life wrought by the pandemic, we should expect an even smaller share of Americans to have relationships with their neighbors today.

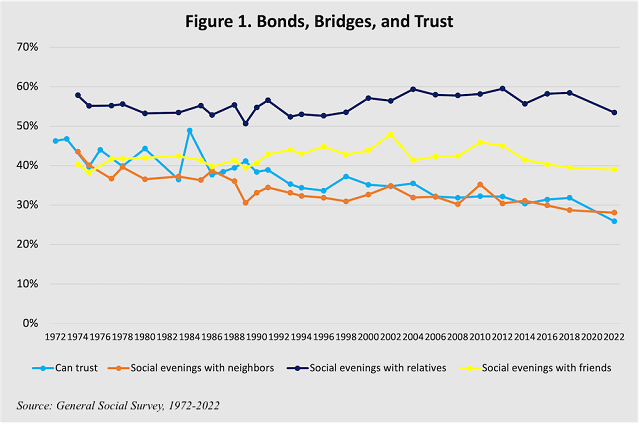

Thankfully, the long-running General Social Survey allows us to observe the strength of Americans’ bonding and bridging social capital. While much has been said in recent months about rising loneliness and isolation in America today, the data show that our bridges tend to be much weaker than our bonds. Figure 1 presents four trends over the past half century: the light blue line shows the percentage of Americans who say that others can generally be trusted. The navy blue, yellow, and orange lines show the share of Americans who report spending a social evening with relatives, friends, and neighbors, respectively.

Over the past half-century, Americans are about just as likely to spend a social evening with a friend or at least “several times per month.” From 1974 to 2018, the share of Americans who spent a social evening with a relative at least several times per month remained unchanged at 58 percent. And over the same time period, the share of Americans who spent a social evening with a friend changed only from 40 to 39 percent. (It is worth noting, however, that data from time diaries show that Americans are spending fewer minutes per day with friends, and more time alone—suggesting that our close ties may not be as stable as these findings suggest).

But the trend looks quite different when examining the strength of our bridging networks. The share of Americans who spend a social evening with a neighbor at least several times per month has declined from 44% in 1974 to 28% in 2022. And the declining frequency of interactions with neighbors has moved in lockstep with declines in social trust. In the early 1970s, 46% of Americans said that others could be trusted, whereas only 26% of Americans say the same today.

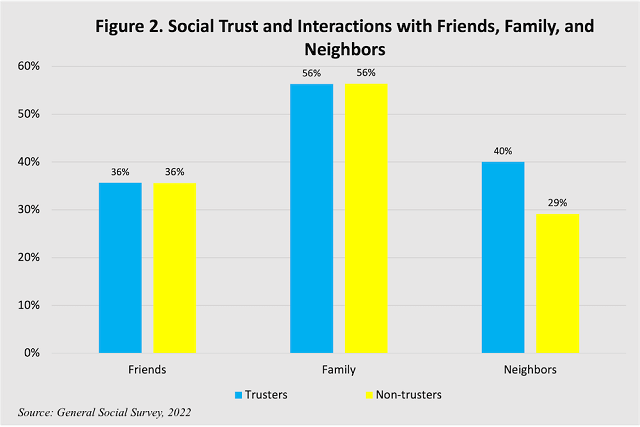

To be sure, our social trust is in large part dependent on the strength of our social connections. But these findings suggest that, when it comes to building social trust, our more tenuous social connections may be more important than our closest ties. Figure 2 shows the percentage of trusters and non-trusters who spend a social evening with a friend, relative, or neighbor several times a month or more.

Social trust has virtually no relationship with the frequency of social interactions with members of one’s bonding networks. In the most recent year of data, equivalent shares of trusters and non-trusters spent a social evening with a friend (36%) or family member (56%) several times per month or more. But trusters are significantly more likely than non-trusters to spend a social evening with neighbors (40% compared to 29%). Our ever-worsening trust crisis appears to be fueled more so by interactions with community members than interactions with friends and family.

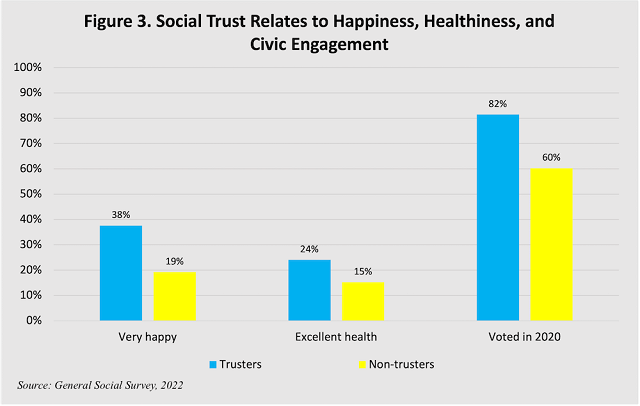

Why does this all matter? It matters because social trust is such an important predictor of myriad benefits for individuals and societies alike. High-trusters, for example, are much happier, healthier, and more civically engaged than non-trusters. Figure 3 shows the divide between trusters and non-trusters in all three domains. Those who trust others are much more likely to report being very happy and in excellent health compared to those who are less trusting. Trusters also vote in presidential elections at much higher rates than non-trusters (82% compared to 60%).

Over the past several months, our national media, politicians, and federal government have started to wage war against loneliness and social isolation—and with good cause. Americans are spending less time with friends and more time alone, and many of the activities that we once did together are becoming relics of the past.

But as we have increasingly focused on loneliness and social isolation, we may have neglected to realize that Americans’ bridging networks are in crisis. Over the past 50 years, we have become about half as likely to spend any social time with our neighbors; we’ve also become half as likely to trust our fellow Americans.

Because social trust is a prerequisite for a contented and well-functioning society, perhaps it is time to get to know our neighbors again.

Thomas O’Rourke is a policy researcher and writer who studies social capital, economic mobility, and anti-poverty policy.